In the late 1980s, basketball was a sport on the rise.

Fuelled by stars like six-foot-nine Magic Johnson, six-foot-10 Larry Bird and a young six-foot-six upstart named Michael Jordan, interest in basketball had grown dramatically from its dark days in the 1970s, when NBA playoff games were broadcast on tape delay.

Thirty years ago this summer, a group of businessmen hoped to cash in on the sport’s growing popularity by creating a new professional basketball league with one big (or small) difference: all players had to be under six-foot-five.

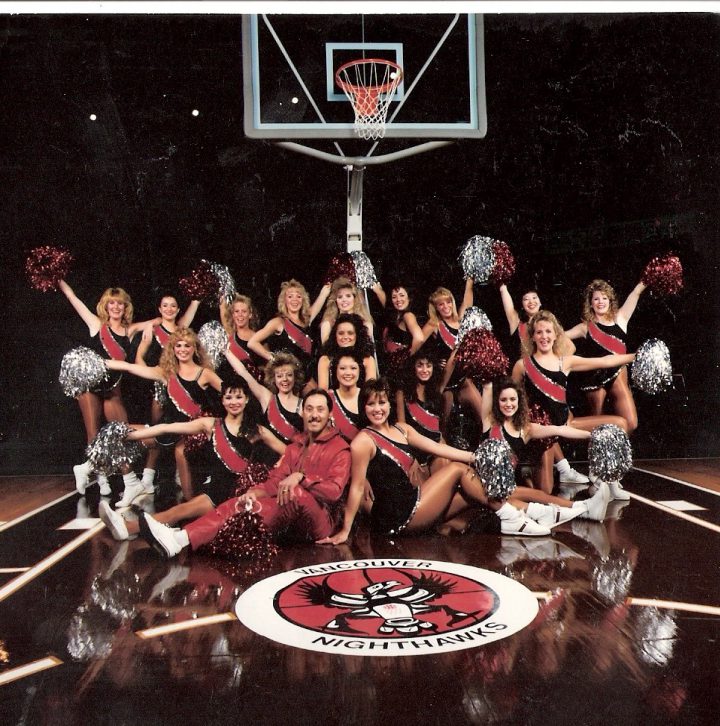

That group included Don Burns, who decided it was a good idea to put one of the World Basketball League’s six franchises in Vancouver and play home games at the cavernous B.C. Place stadium.

In their first and only season in the WBL, the Vancouver Nighthawks finished dead last in the standings. Off the court, the team was a mess. When players weren’t complaining about not getting paid, they were getting into fistfights with each other. In a scene out of a WWE pay-per-view, one player hit a teammate with a folding chair. Then there was a strange controversy about a so-called “incredible shrinking” basketball player who appeared to go to great lengths to dodge the league’s height requirements.

League organizers hoped the WBL would showcase smaller, athletic basketball players who could play a more uptempo style. The league featured a handful of players with NBA experience and many who had successful college careers, but never quite fit the NBA mould.

The NBA had Michael Jordan, but the WBL had Larry Jordan, Michael’s older brother who stood five-foot-nine.

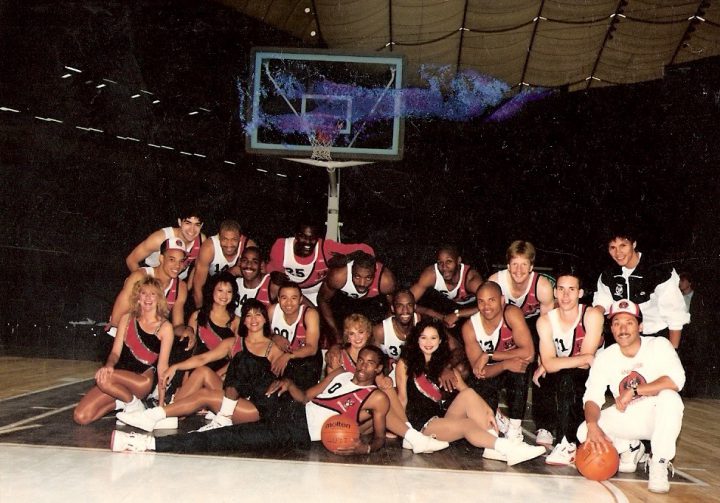

The Nighthawks’ roster featured undersized but athletic players like Jose Slaughter, who had NBA experience, and Willie Bland, who was a star at Louisiana Tech where he played alongside future hall-of-famer Karl Malone.

The Nighthawks played their first home game on May 23, 1988 in front of more than 3,000 fans at B.C. Place, which at the time could house more than 60,000 people.

“It felt hollow,” former Nighthawks assistant coach Phil Langley said of playing in B.C. Place.

“You could hear crickets,” added former Nighthawks point guard Chris Nikchevich.

Things only got worse from there.

Early on, money was tight and players were rarely paid in full or on time.

General manager Jerry Weber was known to hand envelopes of cash to head coach Mike Frink to distribute to players.

“It was all over the board,” Nikchevich said. “You were just hoping to see anything — American money, Canadian money. You didn’t know what was coming from one day to the next.”

Owner Burns, who was based in California, was rarely seen in Vancouver and some players had little trust in Weber, who Burns brought in from California to run the team.

- 35 court dates and no trial: Family of B.C. double homicide victims frustrated by delays

- ‘Embarrassing’: Vancouver councillor calls out mayor over drugs comment controversy

- ‘Like a spelling mistake’: B.C. teen’s DNA ‘corrected’ to cure rare disease

- ‘Ghosted’: Canadians stranded in Puerto Vallarta say they are abandoned by WestJet

Nikchevich remembers him as a fixture in the Los Angeles basketball scene, but others had a more blunt assessment of Weber.

Get breaking National news

“This guy I wouldn’t trust with anything,” said Doug Eberhardt, a local basketball coach who tried out for the Nighthawks. “He was the guy selling you swamp real estate in Florida.”

“Like something out of a Wild West TV show”

The team’s losing ways and lack of steady paycheques led to plenty of frustration that spilled onto the court.

The team was involved in a bench-clearing brawl during a game against the Calgary 88s, which was sparked by Nighthawks forward Andre Patterson. During the fight, Weber scrapped with 88s assistant coach Cory Russell, who ended up in hospital.

Nighthawks players also weren’t shy about throwing punches at each other.

During halftime of a home game at B.C. Place, Patterson got into a heated argument with teammate Willie Bland.

“Andre started chirping at Willie,” Langley said. “Andre wanted the ball and he wasn’t getting it and he was blaming Willie so they were yapping at each other all the way down the tunnel. They were ahead of me and by the time I got there, I turned the corner and they were squared off, throwing punches.

“Willie picked up a chair and knocked Andre down. It was one of those B.C. Place chairs that was metal, heavy metal. He picked it up and whacked him right across the back with it.

“It was like something out of a Wild West TV show.”

At the start of the second half, Patterson and Bland “went out and played and you would never have known anything happened,” Langley said.

Nikchevich said there were other fights between teammates that happened behind closed doors and stayed there. Nobody, he said, ever seemed to hold a grudge.

“There’d be a brawl in the locker room, then afterwards everybody’s at the bar talking about the game,” he said. “It was a team with no memory.”

Andre the giant?

Throughout the team’s brief history, Andre Patterson loomed large. His mercurial personality often rubbed teammates the wrong way and his towering frame had some question whether he, in fact, was too tall to play in the WBL.

While playing on other teams, Patterson was listed at six-foot-eight, well above WBL standards.

Weber chalked it up to the fact that basketball players often fudge their measurements to get an edge in a sport where height is highly valued.

Prior to the start of the season, league officials measured Patterson to see if he was under six-foot-five. Langley remembers seeing Patterson doing whatever he could to make the cut.

“We were practising one day at St. Thomas More high school and the league informed him that he was going to be measured that night,” he said. “So for the entire practice and after practice he walked around with this huge weighted collar around his neck to try and compress his spine. He also had a way of hunching his neck down a little bit.

“The next day I said, ‘How did that session go last night?’ He said, ‘I fooled that guy’s measuring stick.'”

According to the league, Patterson stood six-foot-four 5/8 inches.

The Province newspaper questioned Patterson’s height, dubbing him “The Incredible Shrinking Man.”

Weber called a press conference at a Vancouver hotel to have Patterson officially measured in front of cameras for all the world to see.

The stunt proved to be the most attention the team ever received, even earning a write-up in the New York Times.

On that day, Patterson measured 196.2 centimetres, or six-foot-five 1/4 inches.

The fact that he was too tall to play in the WBL didn’t seem to faze Weber, who said he was satisfied with the whole event and the result didn’t affect Patterson’s status with the team.

“That’s life,” he said.

Nighthawks down

As the season wore on, Nighthawks players grew more angry about not getting paid.

Nikchevich said some players met with a lawyer to see what their options were.

Things came to a head when players threatened to walk away from a June 29 game unless they were paid. The team gave each player a $1,000 advance.

Days later, the league’s board of governors voted to take over the franchise from Burns.

Jose Slaughter, who was the WBL’s leading scorer, demanded a trade, telling a local reporter that the team was a “joke.”

Slaughter got his wish when he and Bland were traded to the Youngstown Pride in July.

After leaving the WBL, Bland was later barred from a basketball league in the Philippines following allegations of game-fixing.

The owner of the Youngstown Pride faced far more serious allegations after the league folded in 1992.

In 1995, Mickey Monus was convicted on 109 counts of fraud and embezzlement that sent his company, Phar-Mor, into bankruptcy.

According to court documents, the company’s “subledger included unauthorized payments to the World Basketball League (“WBL”), a financially troubled professional sports league, in which defendant had invested heavily and of which, he was the majority owner.”

“Prosecutors said Monus looted the company to bankroll a lavish lifestyle and prop up his failed World Basketball League sports venture,” according to an Associated Press article at the time. “He was accused of diverting $8.8 million to the minor-league WBL and more than $500,000 for his own uses.”

As for the Nighthawks, they finished their first and only season with a league-worst 18-36 record.

A group of local businessmen hoped to bring the team back, this time named the Vancouver Kodiaks, but plans never materialized.

Perhaps the league’s greatest legacy was its style of play. At a time when many NBA teams played a more plodding style that relied on big men, the WBL played a high-energy game that more closely resembles the modern NBA.

Eberhardt noted that the WBL was “very much like the style of play in the NBA now with small-ball lineups and three-point shooting and faster pace.”

Nikchevich said he likes to think of WBL players as “gunslingers” who thrived in an uptempo style.

“It was way ahead of its time,” he said.

“It was a totally different mindset. The game is more wide open now and that’s the way that whole league was set up.”

— With files The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.