Idil Shirdon thought her brother was just maturing when he found religion in his late teens. And when he started talking angrily about Syria, neither she nor her mother suspected he was thinking of going there.

But then he disappeared.

Weeks later, the unemployed 20-year-old was calling himself Abu Usamah and raving on video about destroying the West. Farah Mohamed Shirdon had joined the so-called Islamic State.

“They were both unaware that Shirdon was contemplating leaving Canada, let alone joining a terrorist group,” the RCMP wrote in an affidavit after interviewing the Calgary family.

A Canadian study of the families of foreign terrorist fighters has found that’s a typical pattern and called for more education and resources to help parents recognize and confront radicalization.

“Families are likely to be the first to detect something is happening,” said the study released Thursday by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue. “A significant opportunity is being missed to detect radicalizing youth sooner.”

The recommendation was one of four in the report, based on interviews with the families and friends of extremists who left Canada, the United States, United Kingdom and Europe for Syria and Iraq.

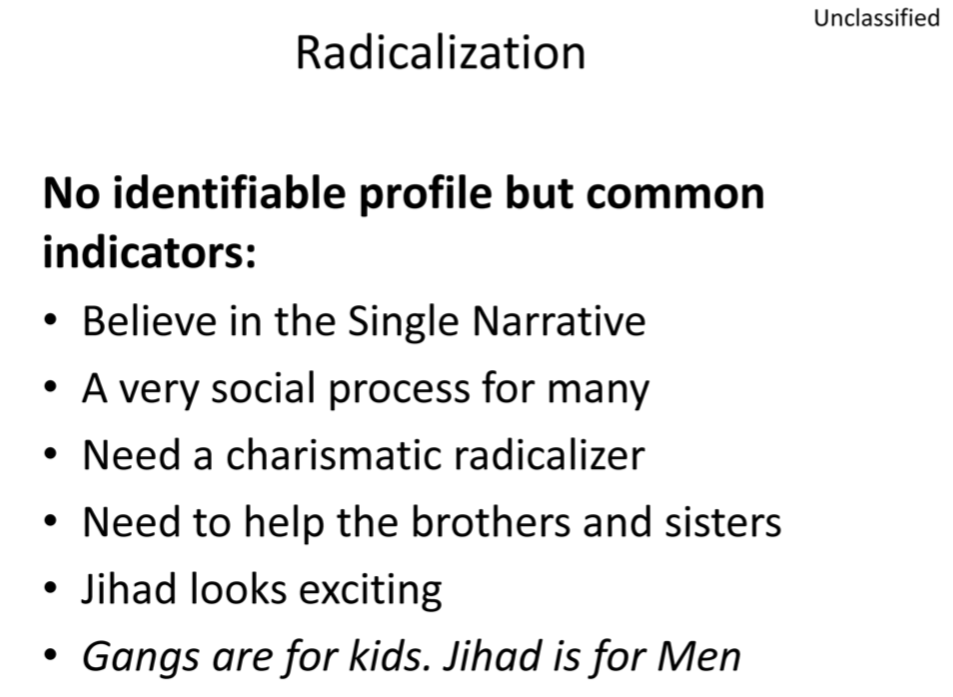

After Canadians began joining terrorist groups in the region, the RCMP published a Terrorism and Violent Extremism Awareness Guide and began working with community groups to discuss the problem.

But the researchers said the parents they interviewed generally had little grasp of what was happening as their children were embracing extremist violence, and were “largely at a loss” about what to do.

Get daily National news

“There should be more public education about the process of radicalization leading to violence for families of potential foreign fighters, and more resources given to this,” said the study, titled I Left to be Closer to Allah: Learning about Foreign Fighters from Family and Friends.

Told of the recommendations, Alexandra Bain, director of Hayat Canada Family Support, which helps the families of violent extremists, said families were usually the first to notice the signs of radicalization but few were able to recognize them.

“The families of jihadists can be our greatest asset in the fight against violent extremism, right from the beginning,” she said.

“Unfortunately, most parents don’t know what it is they are looking for.”

“Public education into the processes of radicalization and extremism is extremely important but is not being adequately supported either by the government or the private sector.”

WATCH: Ottawa foreign fighter wanted by the RCMP

Amarnath Amarasingam, a senior Institute for Strategic Dialogue research fellow, and University of Waterloo sociology professor Lorne Dawson, interviewed the parents, siblings and friends of 30 foreign fighters, 57 per cent of them born to Muslim families while 43 per cent were converts.

The study found that families were reluctant to speak to authorities, fearing they would lose their jobs and be labelled the parents of terrorists. The report called for a more supportive response to parents.

Police should team up with community groups, religious leaders and social workers to help families cope, it said, adding many of the parents struggled with drugs, alcohol and depression after their children left.

Noting that almost three-quarters of the foreign fighters continued to communicate with their families after leaving, the study said more could be done to coach parents on what to say to them.

“These moments of contact between parents and their children provide important opportunities to plant seeds of doubt, encourage the children to return, or at least leave the zones of conflict for a safer place,” it said.

Close friends often saw the changes in behaviour that occurred during violent radicalization more clearly than parents, said the report.

WATCH: RCMP Assistant Commissioner James Malizia talks about how the RCMP deals with returning foreign terrorist fighters.

Among those interviewed were the friends of Shayma Senouci, who was 18 when she left Montreal in 2015 for ISIS. An email Senouci sent her friends after arriving in Syria claimed it was “impossible for a Muslim to live in a country of infidels” and it was an obligation to move to “where Allah’s laws are applied.”

Friends recalled that Imad Rafai, also from Montreal, complained about the Quebec Charter of Secular Values and advocated violence. “He kept saying we should kill them,” a friend recalled.

Shirdon was killed in a coalition air strike in Mosul on July 13, 2015, according to the U.S. military.

But with an estimated 190 extremists still active in overseas terrorist groups, another 60 who have returned, and following several attacks, Canada has been trying to figure out how to tackle violent radicalization.

Canadian security officials rank attacks by extremists inspired by ISIS and Al Qaeda as the country’s top terrorism threat, along with trained, hardened extremists returning from overseas conflict zones.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.