The story would have been alarming if true: only four days after a school shooting killed 17 people at a high school in southern Florida, the FBI was investigating threats to a middle school in Miami.

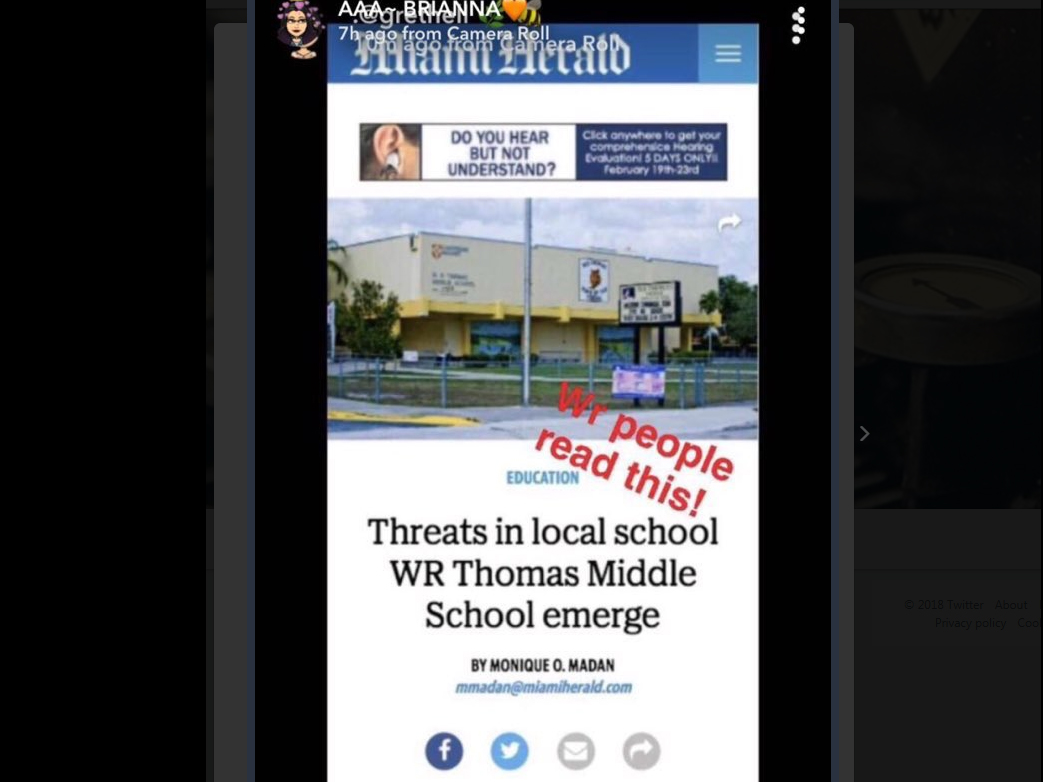

There seemed to be a lot of reason for alarm. A story screenshotted from the Miami Herald‘s website quoted the school’s principal and a school board official discussing the threat.

The image looked convincing enough – it had the paper’s logo, followed its style rules, and carried the byline of Herald reporter Monique Madan.

But as Madan pointed out, the screenshot was of a doctored version of this genuine story, which covered, among other things, a rash of shooting hoaxes in the aftermath of the Parkland shooting. The fake story reused some quotes from the real one, and attributed a fake quote to the school’s real principal.

The fake seems to have originated on Snapchat, Poynter reported.

It has to be said that the fake story itself, which is full of clumsy turns of phrase and evidence of poor proofreading, doesn’t pass careful scrutiny. But it wouldn’t get careful scrutiny in all contexts.

Creating a fake like this isn’t all that challenging.

We’ve written about it in the past in relation to faked screenshots of tweets. but the principle is the same: many browsers will allow you to change the text in your local copy of a file (the text and images on a website that your browser has downloaded) to anything you like. In the case of a newspaper site, if you screenshot the altered result, it will have the original source’s URL at the top, and look perfectly real.

(Here’s a longer explanation, with screenshots)

The only thing I’d add is that it’s even easier than I realized when I first tried it. In Chrome, highlight at least some of the text and click Inspect.

Get breaking National news

There aren’t any real solutions to this, other than only trusting screenshots if you trust the source.

Experts classify this kind of fake as ‘imposter content‘ – it aims to borrow the authority of a media organization or government authority to support a deception. A few examples have appeared over the past few years (most a lot more sophisticated than the Herald fake).

The New York Times was the victim of a similar but much more ambitious fake as far back as 2012. Orchestrated by Wikileaks (which later took responsibility), it purported to be a column by former editor Bill Keller defending Wikileaks against a boycott by credit card companies. It copied the look and feel of the Times Web site, and used real quotes from things Keller had said in a different context.

In 2015, a faked Bloomberg article claiming that Twitter had a US$31-billion takeover offer shifted the platform’s stock price, at least temporarily.

In 2017, a group of Russian hackers staged an elaborate hoax in which they mocked up a faked version of the Guardian site, complete with a URL in which the ‘i’ in Guardian was replaced with the Turkish character ‘ı’.

The story purported to quote former British intelligence chief Sir John Scarlett as saying that a revolution in ex-Soviet Georgia was orchestrated by British and American spies. You can see an archived version here. The technical sophistication of the fake was far ahead of its editorial content, which involved very shaky English, but at the time, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab thought it might have been intended for a Russian-language audience.

A range of sites offer customized fakes of any number of things; quality and reliability vary:

- Ifaketext, ‘the first iPhone text message screenshot generator,’ does a fairly plausible job of faking at least the first screen’s worth of a text exchange.

- However, two services that offer to fake Facebook conversations and status updates didn’t work when we tried them.

- Ticket-o-Matic creates fake boarding passes, but we doubt they would get you very far in a real airport.

- Expense-a-steak said it would create fake restaurant receipts. It doesn’t work, which is probably just as well.

Our suspicion is that many of these sites lost their point when text became easy to edit in browsers.

In fake news news:

- Machine learning will figure out what you want and give it to you efficiently. It has no ethical filters at all, though, as we seem condemned to find out over and over and over again. A recent example: YouTube learns from searches for ‘crisis actor‘ that you want “rape game jokes, shock reality social experiments, celebrity pedophilia, ‘false flag’ rants, and terror-related conspiracy theories,” and serves them up efficiently, Jonathan Albright explains in a Medium post. In the Washington Post, Albright calls it a “conspiracy ecosystem … YouTube has allowed this to flourish.”

- In the past, we’ve referenced the Hamilton68 dashboard, which tracks 600 accounts linked in one way or another to Russian influence operations. It’s one way of finding out what Russian propagandists want to talk about with Western audiences, but a useful BuzzFeed story points out its limitations:”It is true that Russian bots are a conspiracy theory that provides a tidy explanation for complicated developments. It is also true that Russian influence efforts may be happening before our eyes without us really knowing the full scope in the moment.”

- An apparently genuine cache of documents leaked from the Internet Research Agency, a Russian troll farm, offers a trove of new details about its efforts to stoke unrest of one sort or another in the U.S. in 2016. The IRA (the Russian one) had a large budget, the Daily Beast explains, but “they knew far less about how users authentically interact with each other (online)—which itself attracted suspicion amongst the very people the Russians were contacting.”

- As a presidential candidate in 2016, Donald Trump got better value for his Facebook ads than Hillary Clinton did, because his ads were more inflammatory and therefore had more engagement, Wired explains. “Clinton was paying Manhattan prices for the square footage on your smartphone’s screen, while Trump was paying Detroit prices. Facebook users in swing states who felt Trump had taken over their news feeds may not have been hallucinating.” Long read, worth your time.

- In the New York Times, Farhad Manjoo looks at a new generation of intelligent cameras that “use … so-called machine learning to automatically take snapshots of people, pets and other things they find interesting.” They can learn to have a deep knowledge of your world, including facial recognition of family members, but the obvious question is: do you want them to?

- Media Matters looks at how ” … far-right German trolls are organizing to game YouTube algorithms into making far-right video content trend and orchestrate harassment campaigns against political opponents.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.