Editor’s note: After reading this blog, Dr. Jack Newman reached out with several concerns, including that his quotes about breastfeeding were taken out of context and implied that breastfeeding is meant to be difficult. In order to address this, we invited Newman to discuss his thoughts on Family Matters radio. Scroll down to hear the conversation.

I suffer from breastfeeding envy. The symptoms include regret, guilt, longing and admiration for those who can.

I had every intention of breastfeeding my first son, Bennett. He was born in February 2012.

We got off to a really bad start with a perfect storm: an emergency C-section, a spinal headache from the epidural and low weight gain from birth. We were encouraged to start supplementing and were given formula in the hospital. A few weeks later, Bennett and I joined a mom’s group run by Alberta Health Services.

We played an ice-breaker bingo game where we had to go find someone in the room who matched the square. Out of 18 moms, I was the only who had given a bottle. I had to be everyone’s square for “bottle fed.” I think this is where shame around formula feeding set in.

I met with lactation consultants and spent a small fortune on breast pumps, nipple shields, lactation aids, prescribed domperidone and herbal supplements.

I struggled with low supply and after four months of trying — I decided to stop. But I had an excuse that I could live with: We had a rough start.

Nearly three years later, with my second son, I was convinced I could do it. I changed my mindset from: “I hope I will be able to breastfeed” to: “I am going to breastfeed.” I was ready.

I read books in anticipation and I asked lots of questions. After Camden’s arrival, I immediately asked for a referral to an Edmonton breastfeeding clinic. I asked the nurses at the hospital to help every two hours. I had him latching quickly. We were into a routine and after a week he was gaining weight. Then he was not. And that’s when I lost it.

There were low points, a lot of low points.

Rigorous weighing and note-taking

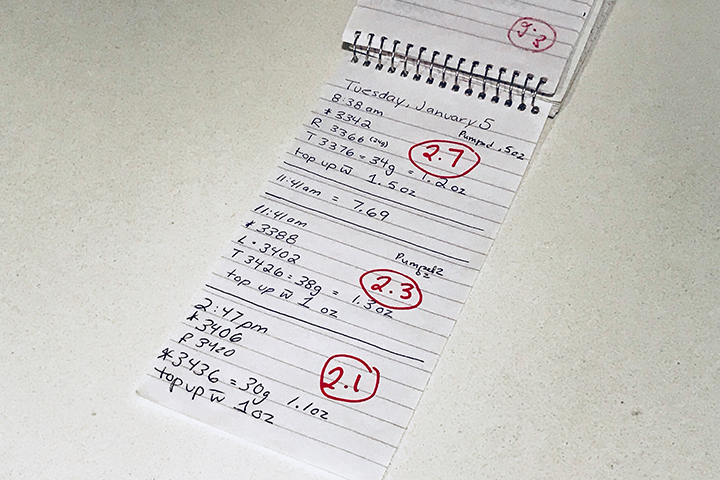

A lactation doctor I was seeing encouraged me to rent a scale to weigh my baby before and after feeds to see how much milk he was getting. I would plot it all down and then top him up with what I was pumping after the feed.

I was obsessed with tracking his weight. After two weeks of a manic weigh-feed-weigh-supplement-pump routine, the lactation doctor sensed something was wrong. She said I couldn’t sustain this and advised me to stop pumping and supplement with formula. I begged for just one more week.

Get daily National news

Convincing my best friend to feed him

In a moment of desperation and still with the scale in my possession, I asked my best friend — who was breastfeeding — to feed Camden. She asked several times if I was sure and agreed.

We weighed him and she put him on her breast. Everything that I had read that was supposed to happen, happened. His eyes flew open. He was alert. You could easily see the big swallows. She was able to feed him in two minutes, the equivalent of what I could in 20 minutes.

We agreed it probably wasn’t good for me to witness this again, but I supplemented him with her expressed milk for months.

Confessing I went against medical advice

The health nurses were on me to start supplementing with formula. He was now four weeks old and not gaining enough weight on breast milk to stay on the curve.

At his appointment with the paediatrician, I asked the doctor to tell me what would happen if he didn’t gain any weight this week. Or the next week. Would he just not grow? Would his brain not develop?

She said it would have to be long-term malnourishment and agreed to give me another week to see what I could do on my own before giving him more formula.

The broken breast pump

One evening as I was about to begin my nightly ritual of feeding-supplementing-pumping-sleeping (repeat three times), I broke the breast pump. The motor was no longer working, which meant I couldn’t function either.

I was hysterical and on the verge of a breakdown. The stores were closed and I would have to wait until the morning to send my husband out to get one. How would I survive the night without losing my supply?

The intervention

Following the broken pump and my inability to supplement with formula, my husband was ready for a heart-to-heart. He was supportive from the beginning; driving me in a snow storm to my first lactation appointment, taking shifts on the weigh scale and even warming up my best friend’s breast milk. He said to me” “Who are you breastfeeding for?” I immediately answered, “Camden” but that wasn’t the truth. I was breastfeeding for me.

I also wanted someone to tell me that I should stop. I wanted someone to look at everything I had done and say, “You did the best you could, but it’s time to quit.”

I wanted a checklist that I could go through. For example, if you can’t produce more than two ounces of milk every two hours — stop. Or if your supplementing milk is three times more than your expressed milk — quit.

Even today, I still want to know that I did everything I could. I emailed my hero and companion from all those nights obsessing over breastfeeding, Dr. Jack Newman. He is a Toronto paediatrician and author who runs a breastfeeding clinic and offers a super helpful Facebook page with videos.

Newman tells me in his career he has never recommended someone to stop breast feeding. Not once. He believes that decision should be when both mom and baby are ready.

He did offer this insight.

“What’s surprising is not how many mothers have difficulty with breastfeeding; what’s surprising is how many manage in spite of all the obstacles thrown in their way.”

Listen below: Newman addresses the concerns he had with this blog and why he thinks the cards are stacked against many Canadian women from the day they first learn to breastfeed.

I breastfed Camden, supplementing with formula until he was six months old. He ended up calling it quits for me when he got impatient and preferred the bottle. The lactation doctor I was seeing eventually determined that a surgery I had when I was a just a few weeks old on my breast likely cut my milk glands, making production difficult.

I wish I could have made it to that magical one-year mark when I feel like moms get the green light to graduate from breastfeeding. But I have two beautiful, healthy boys who don’t go to a separate school because they weren’t exclusively breastfed. And it’s time I let it go.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.