After hasty media reports in 2011 claimed that congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords had been murdered (she was shot, but survived) journalism professor Dan Gillmor made a case for ‘slow news’ – realizing that in a confusing breaking-news situation, reporters and local authorities need time to gather facts properly, and that readers should be patient.

“As news accelerates faster and faster, you should be slower to believe what you hear, and you should look harder for the coverage that pulls together the most facts with the most clarity about what’s known and what’s speculation,” Gillmor wrote.

Six years later, things are arguably worse.

The misreporting in the Giffords case came from well-meaning reporters under intense pressure making mistakes; the problem now involves aggressively competitive fabricators of ideologically driven fictions exploiting the weaknesses of social platforms.

The Times wrote earlier this week about Elmer T. Williams, a ‘popular right-wing YouTube personality‘ (now kicked off YouTube) who sprang into action after the Texas church shootings last week, quickly publishing videos that first claimed that the gunman was “either a Muslim or black,” and then, when he was identified as Devin Patrick Kelley, that he was “most likely a Bernie Sanders supporter associated with antifa — a left-wing anti-fascist group — who may have converted to Islam.”

A large reason why operators like this are as successful as they are is that if they publish videos in the space between early reports of an incident — or better yet the perpetrator’s name being made public — and the appearance of real information, they can harvest tens, or hundreds of thousands of clicks.

(A variation involves fabricating a perpetrator name to get ahead of the game — here Snopes debunks a fake news report in which the Texas shooter is somebody named ‘Raymond Peter Littleberry‘.)

Google has a similar issue: when there’s intense public interest in someone who has up to that point been unknown, Google’s algorithm tries to meet the demand with information sourced from wherever it can be found.

Some of these places are very murky: in the immediate aftermath of the Las Vegas shootings, Google pulled two 4chan threads falsely naming a man named Geary Danley as the gunman into its top story results, which seemed to lend them credibility.

This time around, a search for Devin Patrick Kelley in the aftermath of the Texas shootings “surfaced an editor of the conspiracy site InfoWars, a parody Julian Assange account claiming the shooter had converted to Islam, and a “news” Twitter feed that’s tweeted a few dozen times since it was created last month,” the Atlantic reported.

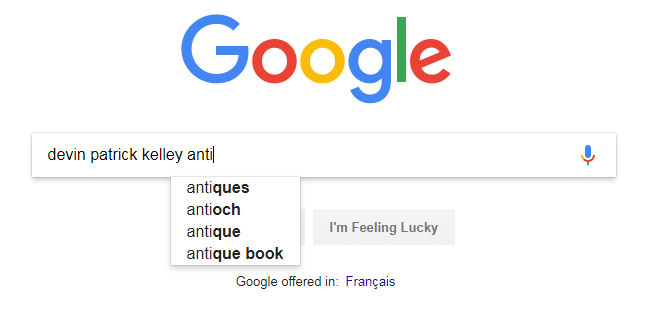

In both the Kelley and Danley cases, the grown-ups woke up and fixed the problem — last Sunday, Google autosuggested ‘devin patrick kelley antifa,’ while now you can’t get that as an autosuggestion if you try (see below), and if you force it as a search term you get a series of factual sources pointing out the lack of a connection.

Facts take a while to gather; shameless invention is a lot faster; truth takes a while to put its boots on. A lot can happen in the gap, though, and the platforms aren’t helping.

READ MORE: Google, Facebook, Twitter face withering scrutiny from U.S. senators over Russian ‘cyberwarfare’

WATCH: Representatives from Facebook, Twitter and Google faced Senators Tuesday at the first of three Congressional hearings looking into how Russia attempted to meddle in the 2016 presidential election through social media.

In fake news news:

Get daily National news

‘We must face this prodigious menace, open-eyed and now’

“We’re building this infrastructure of surveillance authoritarianism merely to get people to click on ads,” argues techno-sociologist Zeynep Tufekci in a recent TED talk.

Tufekci is a shrewd observer of digital culture and a harsh pessimist: ” … Now, if authoritarianism is using overt fear to terrorize us, we’ll all be scared, but we’ll know it, we’ll hate it and we’ll resist it. But if the people in power are using these algorithms to quietly watch us, to judge us and to nudge us, to predict and identify the troublemakers and the rebels, to deploy persuasion architectures at scale and to manipulate individuals one by one using their personal, individual weaknesses and vulnerabilities, and if they’re doing it at scale through our private screens so that we don’t even know what our fellow citizens and neighbors are seeing, that authoritarianism will envelop us like a spider’s web and we may not even know we’re in it.”

Video is here and transcript is here. Worth your time, in a ‘the less you know, the better you sleep’ sort of way.

- This week, attention was drawn to the shadier side of YouTube for children, where low-rent video producers publish randomly rearranged cartoon videos, produced on a vast scale more or less randomly and often with quite disturbing results that seem more or less what would happen if 4chan was allowed to produce children’s programs. (Which in effect it is.) James Bridle has the best take on this I’ve seen so far, linking the problem to the total automation of production by producers and publication by the platforms. “What we’re talking about is very young children, effectively from birth, being deliberately targeted with content which will traumatize and disturb them, via networks which are extremely vulnerable to exactly this form of abuse.”

- The Times has a shorter take, also worth a look. “Algorithms are not a substitute for human intervention, and when it comes to creating a safe environment for children, you need humans,” says one of their interviewees. What we see is a world where producers aren’t all that clear on what they’re making, the platforms have no idea what they’re publishing, and the first human eyes on some of this material can belong to a two-year-old in a high chair.

- NeimanLab talks to Claire Wardle about online misinformation, and the platforms’ responsibility for what they publish. “I just would love to see a way of saying, this technology has already been built, it’s incredibly powerful, and with that power comes really difficult conversations.“

- I’d never heard of Google’s ‘Popular on Twitter’ feature before this week; it seems to not be a very good idea, for obvious reasons.

- In the New Yorker, Masha Gessen reminds us that “Russian online interference (in the U.S. election) was a god-awful mess, a cacophony.” Many of the Russian ads were terrible, and it’s not clear that they influenced anyone’s vote. “Russians generally believe that politics are a cacophonous mess with foreign interference but a fixed outcome, so they invested in affirming that vision. In the aftermath, and following a perfectly symmetrical impulse, a great many Americans want to prove that the Russians elected Trump, and Americans did not.”

- Russian-funded propaganda ads on Facebook turned out to be comically bad — amateurish, culturally tone-deaf. But we should be open to the possibility that they swayed the outcome, Vanity Fair argues. ” … the 2016 election was also decided by only several tens of thousands of voters in a handful of counties where swing voters were already deeply suspicious of Clinton … they latched onto these ideas that people were already hearing, and probably to a certain extent already believed, and hammered them home.”

- In Vox, a long read asking whether the United States, and the West by extension, faces an ‘epistemic crisis,‘ or a crisis in our ability to tell truth from falsity, driven in part by the fragmentation of media. What if Robert Mueller makes an airtight case, grounded in the reality-based community, for Trump’s impeachment, and our information ecosystem is too damaged to act on it? “The only way to settle any argument is for both sides to be committed, at least to some degree, to shared standards of evidence and accuracy, and to place a measure of shared trust in institutions meant to vouchsafe evidence and accuracy. Without that basic agreement, without common arbiters, there can be no end to dispute,” David Roberts writes. A long read, worth your time.

- At Vice, a case that Twitter, “the most open and liberal social media platform(,) has become a threat to open and liberal democracy.” Twitter ” … has built a news platform optimised for disinformation — not by intention, but in effect.”

- Fake news purveyors want to get around our defences with an emotionally compelling story that matches our biases, expert Mike Caulfield argues. “Anything that appeals directly to the “lizard brain” is designed to short-circuit our critical thinking. And these kinds of appeals are very often created by active agents of deception.”

- We’re all vulnerable to bad information, a new study argues — it just has to be bad information that matches your vulnerabilties, which might not be someone else’s, Poynter explains.

- Despite promises to do better, Facebook still swarms with obvious fake accounts, the New York Times reports.

- Less than two months after his death, almost two dozen sites associated with fake news kingpin Paul Horner have vanished, Poynter reports.

- Is ‘fake news’ a useful term anymore? I could argue either side. Claire Wardle argues for a category of ‘information disorder,’ subdivided into ‘misinformation,’ ‘disinformation’ and ‘malinformation.’ I see what she’s trying to do (and politicians denouncing any journalism that’s less than adoring as ‘fake news’ without making any further effort gets old really fast) but I’m not sure how widely used these terms will ever be.

- At the Guardian: “Two Russian state institutions with close ties to Vladimir Putin funded substantial investments in Twitter and Facebook through a business associate of Jared Kushner, leaked documents reveal.”

- Fake news is an easy moneymaker, one purveyor interviewed by Mic says — he moves quickly, and platforms like Facebook respond sluggishly, by which time he’s made his money. “What’s going on here to make that thing magic is that you’ve got real-time news events lining up that are just ripe to be inflamed. Use what is true and implant just a little bit of fake into it. “

- Back in June, hundreds of heavily armed demonstrators showed up in a park in Houston to protest a plan to take down a statue of Sam Houston, They’d been hoaxed — there was no such plan. Months later, though, it’s still not clear who was behind the hoax, though reports that the Internet Research Agency, a Russian troll farm has been trying to organize demonstrations in the U.S. through Facebook accounts they control offers one possibility.

- On U.S. election day a year ago, the Internet Research Agency activated and unleashed a dormant Twitter bot army: ” … sleeper accounts dished out carefully metered tweets and retweets voicing praise for Trump and contempt for his opponent, from the early morning until the last polls closed in the United States.”

- Infowars has republished over 1,000 online stories from RT (formerly Russia Today) in the last few years with attribution but without permission, Buzzfeed reports.

- Thrown off Facebook and Twitter, white supremacists are regrouping on the Russian social networking site VKontakte, the Daily Beast reports.

- A study from the University of Alabama finds that ” … alt-right communities within 4chan, an image-based discussion forum where users are anonymous, and Reddit, a social news aggregator where users vote up or down on posts, have a surprisingly large influence on Twitter.” “Social media platforms & journalists — thus society — are very open to being played by small, organized communities,” Zeynep Tufekci concluded.

- The Philippines has a serious fake news problem, the New York Times reports. Some circulates on faked news sites, some on social media. Mostly, though not entirely, it favours President Rodrigo Duterte. Critics and journalists come in for intense abuse. It’s not clear where the money comes from.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.