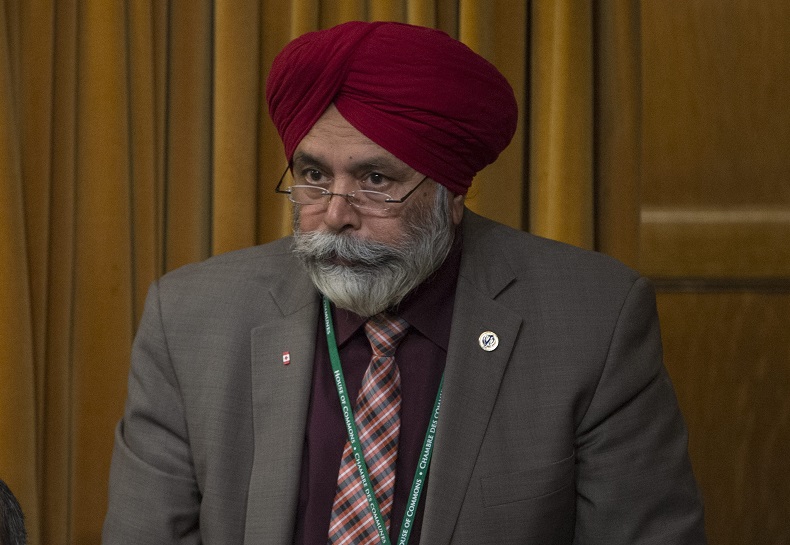

On Thursday night, Calgary’s Darshan Kang became the third MP to leave the Liberal caucus amid accusations of sexual harassment.

Kang, who had faced increasing media scrutiny this week, said he was stepping aside before a formal investigation into his alleged harassment of a young female staffer was even complete.

He explained that “I do not want my present circumstances to further distract from any of the good work being carried out by my colleagues in the government.”

WATCH: Darshan Kang resigns from caucus amid sexual harassment claims

Kang has maintained his innocence and remains a sitting Member of Parliament. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, for his part, had refused to force Kang out of caucus earlier in the week.

“Over the past two years, we have developed here in Parliament a strong series of processes to deal with harassment allegations and complaints of this type,” the prime minister told reporters on Tuesday.

“We will allow this process to unfold as it should.”

But what, exactly, is that process?

The formal name for the set of rules being followed in the Kang case is “The House of Commons Policy on

Preventing and Addressing Harassment.”

The 19-page policy was approved in December 2014, and it applies to all MPs, House officers, research officers and all their attached staff (there are separate sets of procedures in place for when one MP is allegedly harassing another MP, and for administrative staff or unionized employees).

Get daily National news

FROM THE ARCHIVES: 2 Liberal MPs accused of sexual harassment to get permanent boot

The policy applies to all types of harassment, and it places a big emphasis on both confidentiality and prevention.

Parliamentarians and staffers are encouraged to try to work problems out before they become too serious and to educate themselves about conflict resolution through available training programs.

But if a case reaches the point where someone feels harassed or otherwise unsafe, a formal complaint can be filed — usually with the appropriate party whip. That’s exactly what happened in the Kang case, with a staffer in his constituency office in Alberta filing her complaint to Liberal whip Pablo Rodriguez in June.

The complaint itself has to be fairly detailed, and include the following:

- The nature of the allegations

- The name of the person being accused

- The relationship of that person to the complainant

- Date and description of the incident(s)

- If applicable, the names of witnesses

Once the whip has received the complaint in writing, he or she must immediately acknowledge it, and notify Parliament’s Chief Human Resources Officer.

READ MORE: Disgraced Sen. Don Meredith resigns after sex scandal

At this point, “reasonable efforts” can be made to physically separate the complainant from the alleged harasser, by moving them into a different office or position, if needed.

The Chief Human Resources Officer then has to decide if the complaint should be “retained.” If it doesn’t meet the definition of harassment outlined in the policy, for instance, it might be immediately dismissed. Either way, the person who made the complaint is informed of that decision in writing.

Mediation ‘strongly encouraged’

If the complaint moves ahead, it’s at this stage that the person being accused of harassment finds out about it. Both sides are then “strongly encouraged to consider resolving the situation through mediation.”

If they both agree, an outside mediator is brought in, and the two sides sit down (both accompanied by a “support person” of their choice) to try to come to an agreement about how to “redress the situation.”

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Former Hill intern comes forward with allegations of sexual harassment

If that fails, or simply isn’t an option for one side or the other, then a formal investigation is launched. Again, an outside investigator is brought in by the government for this. He or she will review the initial written complaint and the facts, then interview the complainant, respondent and any witnesses.

“Each individual will be interviewed separately and will be required to sign his or her statement, indicating agreement,” the rules state.

The external investigator will then decide, “based upon a balance of probabilities,” whether the complaint is substantiated, partially substantiated, not substantiated or frivolous/in bad faith.

The two sides each get a draft of the investigator’s report, and have 10 days to send in any additional comments they want to see included. Once the final report is produced, they have another 15 days to decide if they want to appeal the decision.

Appealing

If one side is unhappy enough to launch an appeal, that process in itself becomes fairly complicated. It requires the formation of a three-member panel, including one person chosen by the complainant, one chosen by the respondent and one external expert who acts as chair.

READ MORE: ‘Is he going to hit me?’ Government executive abused staff, watchdog confirms

Once the appeal panel reviews all the evidence again and issues its decision, the process is effectively over. Decisions about disciplinary measures can then be made by the whip or supervisors/managers, depending on the situation.

If a complaint involves potential criminal assault or harassment, it can be referred at any point to the appropriate law enforcement agency.

The letters, responses, and reports produced along the way are never made public, although the House is required to publicly disclose how often the harassment policy is used.

There were 19 cases involving harassment, discrimination or abuse of authority during the 2016-17 fiscal year.

Comments