The government of Canada is gearing up for another public education push linked to radon, a potentially harmful gas lurking in high concentrations in close to 1 in 10 Canadian homes.

The long-term effects of inhaling the odourless, colourless radioactive gas have been known for years, but it’s only in the last decade that Health Canada has made a concerted effort to educate people about radon.

After tobacco, it’s the second leading cause of lung cancer in Canada, and is responsible for up to 3,300 deaths per year. But only one in two households has even heard about it, according to Statistics Canada.

Last week, Health Canada issued a call for tender asking for an outside contractor to develop and deliver “a national radon workplace engagement program” as part of its broader National Radon Program.

The project will challenge 80 to 100 employers across Canada to test their workplaces for radon, and encourage employees to test at home. It will be rolled out this November.

“While progress has been made in raising awareness and moving the public and stakeholder partners to action on this issue, we recognize that there is much work left to be done,” said department spokesperson Tammy Jarbeau in an e-mail.

University of Calgary assistant professor and cancer researcher Aaron Goodarzi is considered one of Canada’s leading experts on radon. He said he’s pleased to see Health Canada taking action.

“In my view it’s a very good thing,” he said. “They’re going directly into the workplaces to promote awareness.”

Goodarzi pointed out that of all the cancer-causing agents people are exposed to, radon is one of the easiest to tackle. Nobody’s addicted to it, he noted, and there’s no lobby supporting it.

“It’s possibly the lowest-hanging fruit for a citizen to reduce potentially a lethal source of cancer for them,” Goodarzi said.

“I know people with a Smart TV that costs double what it would take to prevent your family from getting a lethal lung cancer.”

Still, Health Canada says only six per cent of Canadian homeowners have actually tested for the gas.

Who should worry about radon?

Get weekly health news

Radon gas originates beneath our feet, produced by the decay of uranium found in soil, rock or water. It’s found in just about every building.

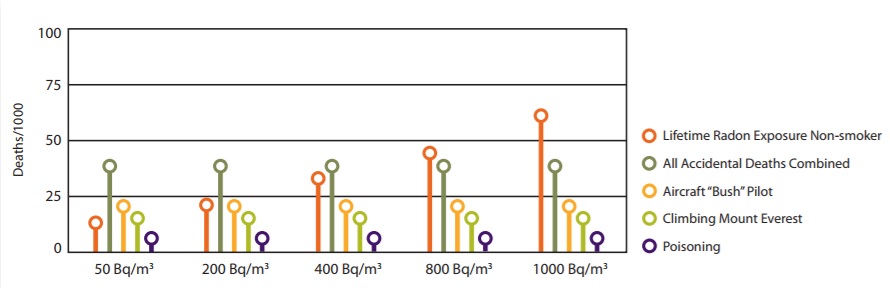

The concentrations are usually too low to cause problems, but anything over 200 Bq/m3 is considered potentially harmful over an extended period of time.

Living for decades in a home with concentrations above 800 Bq/m3 is more likely to kill you than all accidental causes of death combined, according to Health Canada.

New Brunswick, Manitoba and the Yukon tend to have more homes with high concentrations of the gas, but just about every province and territory has a jurisdiction where radon is a major issue.

READ MORE: 1 in 8 Calgary homes exceed Health Canada’s acceptable radon level

In Brandon, Manitoba, for instance, a 2012 cross-Canada survey revealed that a staggering 44 per cent of homes had levels above what is considered safe by Health Canada. The national average is seven per cent.

Goodarzi cautioned that while geography matters, so does construction. In fact, research has shown that newer homes, often sealed more tightly to help with energy efficiency, tend to trap more radon.

“They had on average a 31.5 per cent higher radon level compared to older properties. So it’s not necessarily so much about where you’re living, but it’s in what kind of house or property or school you’re in.”

In short, he added, everyone should be concerned, and everyone should test.

What can homeowners do?

Testing is relatively simple and inexpensive, and can be done by homeowners using a kit purchased online or from home improvement stores.

Heath Canada recommends using a kit that measures radon on the lower levels of a building over a period of at least three months during the winter, when windows are kept shut. Homeowners then send the kit in for lab analysis.

The other option is to hire a professional, preferably one certified under the Canadian National Radon Proficiency Program.

WATCH: Mike Holmes Jr. spreads message of radon dangers

Fixing cracks, providing better ventilation and other types of remediation that will drastically cut the level of radon in a home will cost between $1,500 and $3,000.

There are currently no federal grants or programs that help offset that cost, and according to a presentation delivered by Health Canada in April 2016, that’s proven to be a barrier for low-income Canadians.

There is help available in pockets across the country, however. The Tarion Home Warranty program in Ontario covers radon mitigation, and the Manitoba Hydro Energy Finance Plan also includes it under their loan program.

But according to Goodarzi, cost is just one reason people fail to test or conduct repairs. Even if you offer mitigation for free, studies have shown only one in two homeowners will take advantage.

“We’re trying to understand the psychological variables around that,” Goodarzi said. “Some of it is simply ignorance of what the process involves. They think they’ll have to rip up their entire basement. That’s absolutely not the case.”

What can governments do?

Health Canada’s symposium presentation last spring also flagged a “lack of radon protection” in many building codes, and noted that increased public awareness about radon “has not led to sustainable policy decisions to support radon risk reduction.”

WATCH: Dr. Michael Dworkind on radon gas in Canadian homes

There is no overarching legal requirement across Canada, for instance, for individuals, schools or businesses to test for radon in indoor air, to lower the levels if they are too high, or to disclose test results. But there’s a good reason the federal government hasn’t stepped up.

“Health Canada can only really advise and sort of prod when it comes to radon,” said Goodarzi.

“At the end of the day, because it’s a naturally occurring component of our geology, it falls under provincial jurisdiction, much like oil and mineral wealth.”

What that means, he said, is that provinces need to lead the way by updating individual building codes, or by providing more financial incentives. Alberta updated its building code to include radon testing and mitigation in 2015, for instance, but Ontario and Quebec are still playing catch-up.

“What the individual provinces can (also) be doing is really waging a public awareness campaign,” Goodarzi said.

“Much like we’ve done in history for smoking, and we’re doing right now very well for tackling problems like obesity.”

To find out more about radon, click here.

Comments