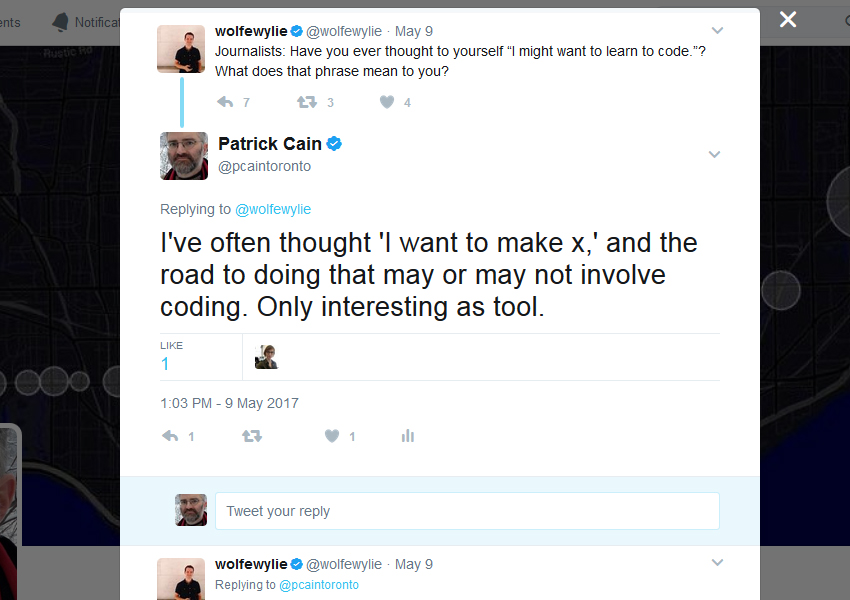

Buzzfeed has an excellent dissection of the faked tweet shown above, apparently from outgoing FBI director James Comey.

(The ‘pee tape’ reference relates to unverified allegations about certain things Donald Trump is claimed to have done in Moscow, claims he has said are false.)

In any case, some people’s filters caught it as a fake, and some didn’t.

A screenshotted tweet of someone saying something revealing, scandalous or otherwise interesting is a very compelling thing. Also, people do tweet indiscreet things and then think better of it. And it can be wise to screenshot tweets of this kind yourself (as I just did) in case they later disappear.

Unfortunately, you can only trust screenshotted tweets — no matter how high-quality they seem — if you saw the original yourself or trust the person who says they did. (In this case, as Buzzfeed points out, the tweet was 153 characters long, which makes the whole thing easy to evaluate.)

READ: Facebook removed over 30,000 fake news accounts ahead of French and British elections

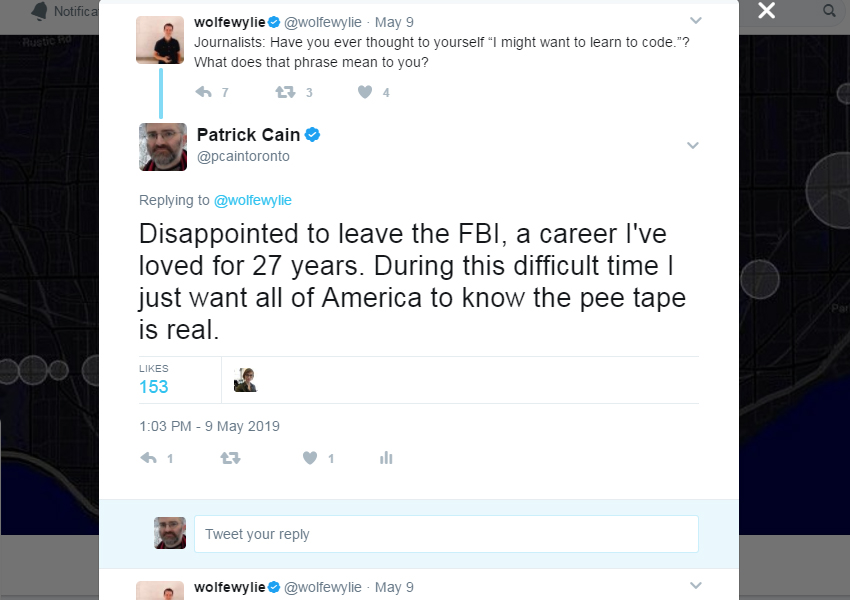

The reason is that it’s very easy to edit a local copy of a tweet (or anything else your browser is looking at) in the browser itself.

Here’s a tweet of mine as it actually exists. We can make it say anything we want to, though:

Before:

During:

After:

READ: How sketchy Twitter rumours led to reports of Prince Philip’s death

Get breaking National news

In fake news news:

- In a Medium post, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab traces how a Russian disinformation operation in April was uncritically picked up by the British tabloids and Fox News. The Russians were claiming that they had successfully disabled U.S. naval electronic systems, and cited as proof an apparent Facebook post by a U.S. sailor written in a really bad attempt at colloquial English.

- The video in which a girl calls Donald Trump a “disgrace to the world” isn’t exactly a fake, having been produced by Comedy Central. (The Trump impersonator featured is more convincing seen from behind.) A version with the Comedy Central logo cropped off, however, was circulated as real.

- A man didn’t sit behind British Prime Minister Teresa May with a sign saying “She’s lying to you,” though this video seems to show otherwise. It’s an example of something we’ve been warned about before, which is that it’s becoming easier to make reasonably high-quality fake videos.

- Of the possible emotions fake or hyperpartisan sites could try to elicit, anger is the most successful, a recent paper argues.

- A recent psychology study found that people who are open to conspiracy theories are more socially excluded than people who aren’t: “… ostracism enhances superstition and belief in conspiracies.” (It’s easy to see it the other way around, too — that people who embrace conspiracy theories are more likely to be ostracized.)

- Vox’s health reporter Julia Belluz traces a serious measles outbreak among Somali-Americans in Minnesota to a campaign (which initially flew under public health officials’ radar) to convince them that vaccination leads to autism.

- WNYC’s Manoush Zomorodi has over 22,000 Twitter followers. More follow her account every day. Trouble is: many of then are bots — really obvious ones. Why are they there? Why do they keep arriving? It’s not clear, but the fear is that ” … they’re aiming to sow chaos and make dialogue impossible. At the extreme, the goal is to destabilize our very sense of reality.” Here’s her podcast.

- Psychological warfare is perhaps as old as warfare itself. Armies have dropped leaflets on the other side, trying to undermine their morale, and later broadcast to their enemies. This week, the AP reported that individual Ukrainian soldiers have been getting texts, presumably from Russia, following very well-worn propaganda themes that could in their essentials have been used at any point in the last hundred years or so. (“Guys, Parasha sold us out to the Yanks. Let’s go attack Kiev instead!” “Who is robbing your family while you are paid pennies waiting for your bullet?”)

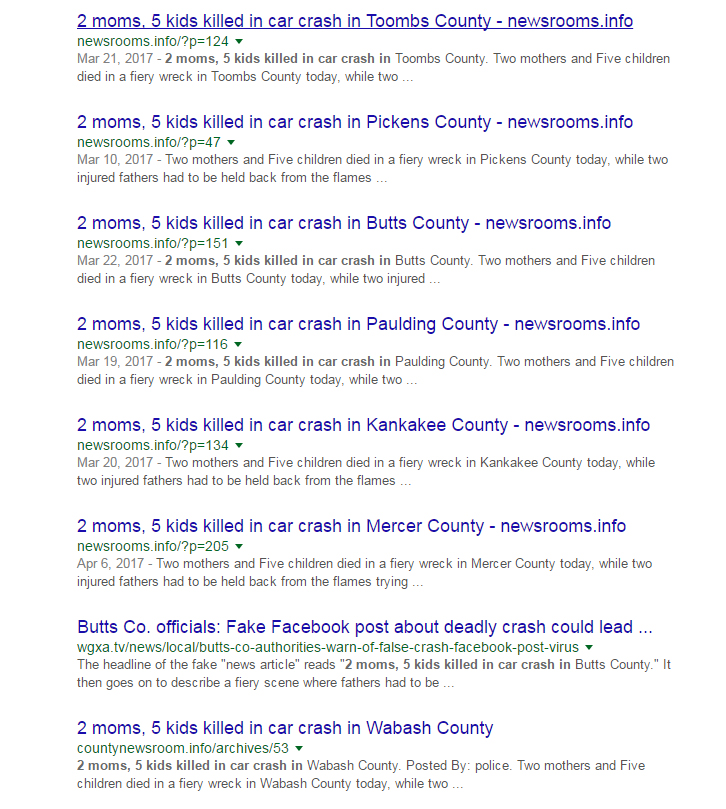

- The AP points out that the (newsworthy thing) has happened in (any number of places) fake news template has resurfaced. (Remember the fake news stories that claimed that Brad Pitt was moving to Brantford, Ont., and also many other places?) In this iteration, a real tragedy in California in 2016 in which two mothers and five children died in a minivan accident has been repurposed in dozens of different places. Google “2 moms, 5 kids killed in car crash in”, and the results will look like this:

Comments