Is there a war on Christmas?

The case has always seemed pretty thin to us, especially since retailers start jingling when the leaves have barely fallen from the trees. If there’s a war on Christmas, it seems barely noticeable, and certainly not very successful.

But every year, as it starts to feel a lot like Christmas, it’s the season for culture warriors to charge into battle in the service of the war on the war on Christmas.

They often seem embarrassingly short on dragons to slay, which is why (for example) fake news sites went to considerable trouble to make the Obamas’ Christmases in the White House out to be more secular than they actually were.

(A 2006 Associated Press story mischievously suggested that for some, a good rousing culture war is part of the pleasure of the holiday season.)

Story continues below advertisement

Is there a war on Easter?

READ: Fake news: Trump, Infowars part ways on Syria gas attack

Well, the concept makes even less sense than a war on Christmas, really. Secular and Christian observances of Easter are much less intertwined than secular and Christian observances of Christmas, and you could make a case that they have no relationship at all.

Which brings us to Britain’s Cadbury Egg Hunt (2017), formerly the Cadbury Easter Egg Hunt (2016), a joint project between the chocolate company and the National Trust, which manages historic sites in Britain. Cadbury gets a marketing opportunity, and the National Trust gets to interest children in the historic sites it manages. Kids get candy and fresh air, and parents get to fill time on a holiday weekend.

The reflexive outrage over the name change included grown-ups who should have known better.

“Easter’s very important. It’s important to me, it’s a very important festival for the Christian faith for millions across the world,” said British Prime Minister Teresa May. “So I think what the National Trust is doing is frankly just ridiculous.”

READ: Fake news: How ads for mainstream brands end up in the Web’s dark corners

“To drop Easter from Cadbury’s Easter Egg Hunt in my book is tantamount to spitting on the grave of Cadbury,” rumbled John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York, referencing company founder John Cadbury‘s Quaker faith.

Story continues below advertisement

“The founder of the Cadbury company was a devout Christian, and I think he would be rolling over in his grave over the thought of this happening — the separation of a country from its historical Christian roots,” Dallas, Texas, Baptist minister Robert Jeffress said on Fox.

“There is a more nefarious motive at work here, and that is that progressive secularists are trying to separate our country, and the world, from its Christian roots in order to further their secular progressive agenda.”

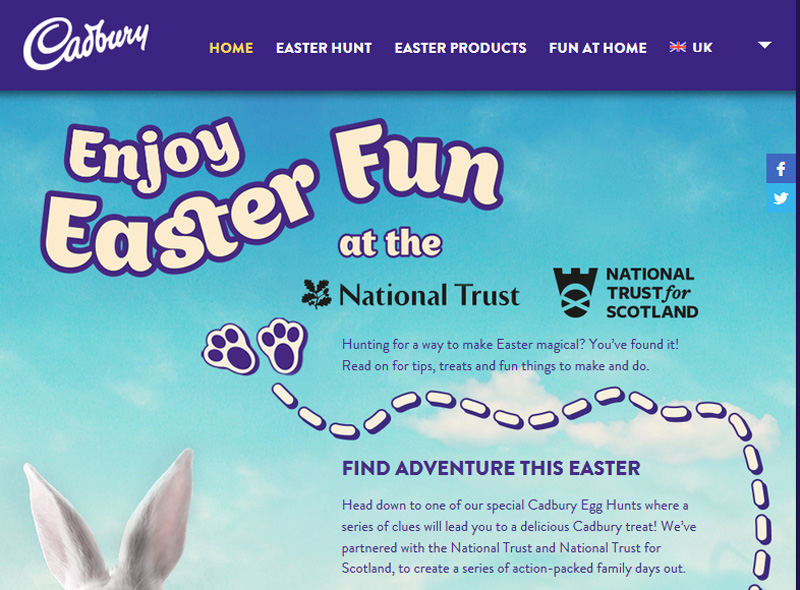

But the problem with this whole line of argument was that the E-word still features prominently in marketing materials from both organizations — as both were quick to point out.

Here’s a screenshot from 2016:

and this year:

Story continues below advertisement

The Easter mentions went from seven to five — if you’re counting.

But what would John Cadbury have thought?

Esther McConnell, Cadbury’s great-great-great-great-granddaughter, delivered a reality check:

“Quakers recognize the equality and value of all people,” McConnell told the Independent. “As such, I am glad to see that Cadburys and the National Trust are welcoming those of ‘all faiths and none’ to their event regardless of whether they call it Easter or not.”

(Addressed by nobody: how an egg hunt sponsored by a chocolate company could function as a religious observance in the first place, even a very indirect one, or why anyone would expect it to.)

Better luck next time, culture warriors — there’s always Christmas to look forward to.

Story continues below advertisement

READ: As always, fake news festered in the aftermath of the London attack

In fake news news:

- Perhaps not surprisingly, business news sites that publish stories “with little editorial oversight” were overwhelmed with material paid for by companies and designed to boost specific stocks, Axios reports. Now, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has charged 27 people with fraudulent stock promotion. “One writer wrote under his own name as well as at least nine pseudonyms, including a persona he invented who claimed to be “an analyst and fund manager with almost 20 years of investment experience,” the SEC says.

- The NiemanLab looks at the world of 19th-century fake news. Papers gained status by having foreign correspondents, but staffing bureaus abroad was inconvenient and expensive. One reporter (if that’s quite the right word) spent a decade working for a Berlin paper as their “London correspondent,” never leaving Berlin and getting by on rearranging scraps of other people’s reports from Britain, plus some fabrication.

- White House spokesperson Sean Spicer had a bad day Tuesday, in which he managed to commit several spectacular gaffes related to the Holocaust during Passover. One thing he didn’t do, though, was imply that German Jews weren’t Hitler’s “fellow Germans.” That was a fabricated statement on a fake Facebook page, since deleted. Snopes and Buzzfeed explain.

- At Buzzfeed, Craig Silverman ponders Facebook’s change of tone about addressing the company’s indirect role in the fake news ecosystem. Facebook has lost much of its former arrogance, he wonders how much of it is substance: “While (senior executives) are ready to talk about its responsibility to the news industry and how to stop false content from going viral, other questions go unanswered.”

© 2017 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.

Comments