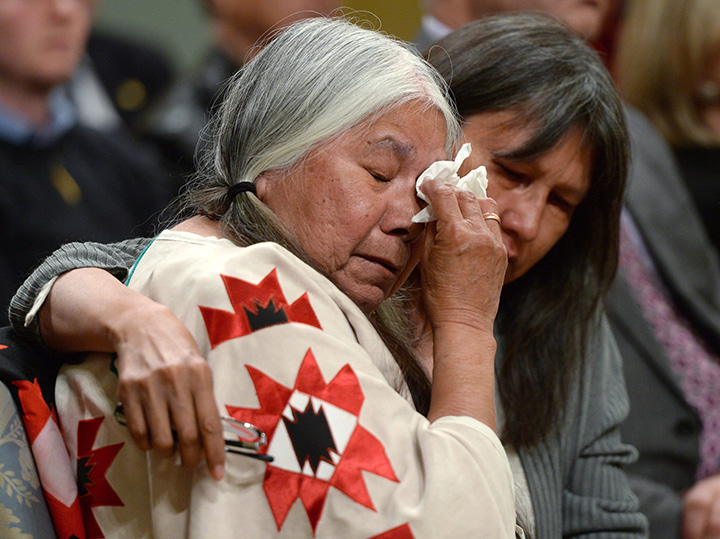

The future of the often heart-rending stories told by survivors of Canada’s residential schools will be decided by the country’s top court.

The Supreme Court of Canada said Thursday it would hear the federal government’s appeal of a decision that the highly personal accounts should be destroyed after 15 years – unless the individuals decide otherwise. The court also ruled Inuit representatives can take part in the case.

The federal government sought leave to appeal to the Supreme Court, arguing it controls the documents and that they are subject to legislation related to privacy, access to information, and archiving.

WATCH BELOW: NDP MP Charlie Angus uses ‘Secret Path’ to attack Liberal government over Residential Schools

The documents at issue relate to compensation claims made by as many as 30,000 survivors of Indian residential schools – many disturbing accounts of sexual, physical and psychological abuse.

The compensation scheme – handled under an independent assessment process known as the IAP – flowed from the 2006 settlement of a class-action suit related to the notorious residential schools.

Get breaking National news

The government, along with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, argued the survivor accounts are a critical part of Canadian history that should be preserved. However, the independent claims adjudicator maintained that claimants were promised confidentiality, and only they have the right to waive their privacy.

“Claimants in the independent assessment process must control the stories of their experiences at residential school,” Chief Adjudicator Dan Shapiro said in a statement Thursday.

“Unless a claimant specifically consents to their records being archived, in order to protect claimants’ confidentiality, documents created and collected in the IAP should destroyed when they are no longer needed in the IAP.”

Initially, a lower court judge ruled the material should be destroyed after 15 years, although individuals could consent to have their stories preserved at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation in Winnipeg.

In a split decision in April, the Ontario Court of Appeal agreed, saying the documents were not government records subject to archiving laws, and their disposition should be at the sole discretion of the survivors.

READ MORE: Residential school survivors’ Thanksgiving reunion

In upholding the shredding decision, Ontario’s top court ruled that claimants who chose confidentiality should never have to face the risk that their stories would be stored against their will in a government archive and possibly disclosed. The court also rejected the idea the documents were “government records” but fell under judicial control.

The dissenting justice, however, rejected that idea, saying the documents should be turned over to Library and Archives Canada subject to normal privacy safeguards and rules.

“If the IAP documents are destroyed,” Justice Robert Sharpe said in his dissent,

“We obliterate an important part of our effort to deal with a very dark moment in our history.”

About 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Metis children were forced to attend the church-run residential schools over much of the last century as part of government efforts to “take the Indian out of the child.” Many suffered horrific abuse.

Material collected separately by the truth commission, which also heard from thousands of survivors, is archived at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba.

WATCH BELOW: Elder shares deeply personal experience with residential schools on Orange Shirt Day

Comments