It’s not often that you hear of astronomers taking on a lot of hate. But for Mike Brown, he’s had to live with being called a murderer. Specifically, the killer of our former ninth planet, Pluto.

In 2003, Brown discovered Eris, a body beyond the orbit of Pluto. Once it became clear that there were many bodies similar to Pluto and Eris at the outer edges of our solar system, the International Astronomical Union reclassified Pluto as a dwarf planet.

This upset a lot of people around the world. Pluto has held a special place in the heart of many, and its oft-referred “demotion” was a bitter pill to swallow.

But Brown asserts that Kuiper Belt Obejcts (KBOs) — icy worlds beyond the orbit of Pluto — are far more interesting than we give them credit for and that we should embrace the uniqueness of these objects rather than consider them lesser worlds.

I spoke to Brown about what it’s like being called a planet killer and the excitement over the possible “Planet X” being out in the great beyond.

So, you killed Pluto? Why, Mike? Why?

- High benzene levels detected near Ontario First Nation for weeks, residents report sickness

- Enter at your own risk: New home security camera aims paintballs at intruders

- Beijing orders Apple to pull WhatsApp, Threads from its China app store

- Boston Dynamics unveils ‘creepy’ new fully electric humanoid robot

Because it had it coming. That’s the obvious answer to that question.

Killing Pluto sounds kind of mean. According to my daughter, killing is not nice and I shouldn’t have killed Pluto. But it … was an amazing moment or period we went through a decade ago of realizing that Pluto is not this lone object out there, but that there are many…there are hundreds of thousands like it. It’s a crowded universe out there and everyone sort of remembers it as the shorthand of Pluto being demoted, but I think of it as an incredible exploration of this region of the Kuiper Belt. The solar system is not eight planets and then one funky little planet at the end that doesn’t make any sense. It’s these eight planets and then tons and tons of objects flitting around in between the planets, being kicked around by the planets, doing whatever the planets tell them to do basically.

The real common characteristic of the eight things that you totally miss if you suddenly conflate the planets to include these tiny things is that the eight planets are these hugely gravitationally dominant objects … They don’t get kicked around; they do the kicking around instead.

What’s been your reaction to being coined the “Pluto Killer”? I mean, that’s even your Twitter handle.

Wait, I’m one of the Pluto people —

But do people actually call you?

Yes. I never answer my phone anymore unless I know someone’s calling or recognize the phone number. But I get phone messages, including this whole series of really quite rude insulting things, that were sufficiently rude that they were using words that I didn’t understand. So I had to ask my much younger graduate students what these words meant and they couldn’t answer because they were just too busy rolling on the floor and laughing so hard. They then refused to tell me. So I don’t actually know what I was being called, but it was apparently pretty good…

Pluto will not be a planet again. It’s just not going to happen.

If we could just all agree that it’s OK to be interesting even if you’re not a planet, then I think we could learn more about the solar system.

How do you feel about New Horizons and its discoveries? Have any of the discoveries — such as the believed geological activity — changed your mind at all about its reclassification?

No, we expected it to be geologically active all along. The findings have been fantastic and interesting and surprising, but the fact that it’s active is not surprising. Many things out there are active, from moons to asteroids to Kuiper Belt Objects. The thing that I find funny is that so many people — again, the people who are nostalgic about Pluto — are like, ‘Now that you see it, shouldn’t it be a planet?’ I think the argument is, it’s interesting, therefore a planet. Which again, this is what … I’ve been trying to argue all along: There are many things out there that are interesting and they’re not planets, and that’s OK.

What was it like seeing Pluto for the first time?

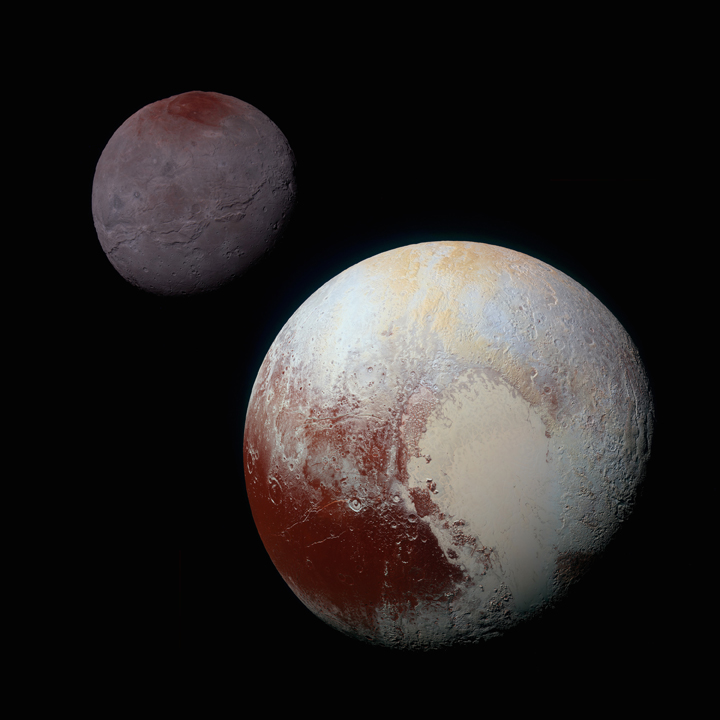

I was sitting there like everybody else, pressing the refresh button on my browser waiting to see what the next image looked like. It was great. Some parts of it were exactly like what was predicted, so it was kind of fun to see those predictions come true. For any space mission, they have to go with the trope that nothing is expected and everything’s brand new, but to me it’s actually much more interesting: we actually knew a lot about Pluto and sure enough, these things are correct. Like the smooth plains on Charon — we knew they were going to be there. We didn’t know exactly what they were going to look like, but we knew they were going to be there. It was a thrill to me to say, you know, 15 years ago I wrote this paper saying that there were going to be these things on Charon, and there they are! And then there’s the stuff that you had no idea were going to be there, like big convecting mounds of nitrogen pulling off icy mountains. Like, oh, yeah, nobody predicted that one. That’s just crazy.

You know there are going to be things you just never even thought of, so those are the fun ones. So it’s a thrill to see things like that.

Tell me about Planet 9. It’s pretty amazing.

But in the meantime, during this whole survey of the Kuiper Belt, we found one odd object: Sedna … It was so weird. It had clearly been pulled away from the Kuiper Belt by something. It never came close to the Kuiper Belt. Everything else we’d found was in the Kuiper Belt or at least goes back to the Kuiper Belt after it goes on its orbit. But Sedna was the only exception. And it was very clear that something had to have pulled it out of the Kuiper Belt, and we didn’t know what. And this was 13 years ago now. I’ve been puzzling over what that could possibly be and looking for more objects like Sedna.

It was that search for more objects like Sedna — and that search also inspired other astronomers to start looking for these — that led to another Sedna-like object. But more importantly it led to the realization that these very distant objects like Sedna, and some other ones that didn’t seem quite so strange, that they’re all being pulled off in one direction by something. And that’s what finally led us down the hole that there must be a big planet out there.

So how is it that we’ve missed it? What about WISE? (Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer space telescope)

Everybody remembers a story from WISE a year or two ago that basically says that WISE ruled out Planet X. But nobody looks at the WISE paper. When you look at the WISE paper you realize they have ruled out Jupiter- and Saturn-sized objects in the outer part of the solar system, and that’s because when you get as big as Jupiter or Saturn, you’re really quite hot on the inside, and that heat is easily visible. Uranus and Neptune are much, much cooler and WISE almost can’t see Neptune at Neptune. Now, it’s not quite as bad as that. But if you put Neptune 10 times further away, it would be invisible to WISE.

What kind of telescope will it take to find it? Will it be the new James Webb Space Telescope?

No, no, no. That would be terrible. Webb is a terrible telescope for this kind of thing. Hubble is equally terrible. Because what you want is a big telescope, but also a big telescope with a wide field of view camera on it. So the key telescope in the world will be the Subaru telescope on Mauna Kea. That Subaru telescope on Mauna Kea has a camera that is — I hadn’t ever thought of this before, but actually when I think of it I think it’s about the right scale — the camera, literally the camera with the electronics and the lenses that sits on top of the telescope, that camera is the size of the Hubble telescope. Not the mirror, it’s the actual size of the entire Hubble Space Telescope … So these ground-based telescopes are critical. Subaru is the biggest telescope in the world with a wide field of view, so it’s going to be the one we’re most hoping to use.

Are you anxious that somebody else will discover this planet?

You know I’m a culmination of being anxious and hopeful. I would love to be the one who finds it. That would be great, but obviously because we told everyone where to look, somebody might find it first. I would like to find it myself, but I would rather somebody else find it than me find it in 10 years. When it’s found, I’m really anxious to get all the telescopes we can to swing around and see what it’s really like.

Do you think it’ll take a long time to find it?

I think we’ll find it in under five years. It’s always possible that we’ll find it tomorrow. I did a big analysis yesterday that would have covered about half its track across the sky and it wasn’t there … So I’m always wondering if I’m just going to open up the newspaper and read that someone else has found it.

If you could go out to any body out there — notice I didn’t say planet — where would you go?

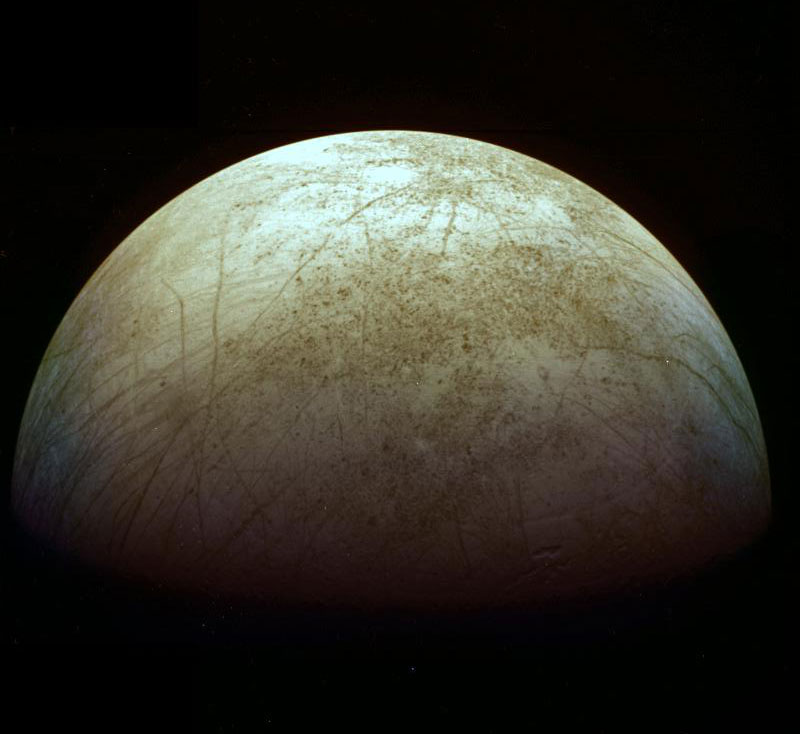

As long as you promise I could stay warm. Wow … that is such a hard question. You have thrown me a question nobody has ever asked me before! So I’m torn. I’m torn between wanting to go to one of these little worlds that I discovered myself. I would love to go stand on Eris and look around and think, “Holy cow. I discovered this whole thing!” and just kind of be amazed and see what it’s like. It’ll have things like Pluto and things that are not like Pluto. So it’s hard to know if I should go there or if I should go somewhere that I know is outrageously cool. I’d love to go to Europa. I would love to go there and dig on the surface and see if I can find a crack and slip down below the ice and go for a swim in the ocean.

If Planet 9 — I almost said 10 —

No. No. Sorry…no.

If Planet 9 is discovered, what name would you like to see it given?

So I have refused to allow myself to think about that yet. Until it’s actaully spotted, it’s just still not real to me. I don’t want to jinx it by giving it a name first. The moment we find it I will start thinking about what’s a good name.

So is there a 0.007 per cent chance that there’s nothing out there?

Uhm…no. I would say specifically that there is a 0.007 per cent chance that you would get those specific alignments in the sky due to chance. Now, that’s not the question, though. The real question to ask — and this can’t really be answered is — what is the chance that you would, presented with a number of objects in the outer solar system that we now know, find a strange pattern? That’s the real question.

Once we came up with this idea of this planet, it predicted other things. And all these other things that we’ve predicted have come true.

You have a pretty amazing job. You should be called a space detective.

Oh. I like that.

And yeah, it’s pretty crazy that I get paid to do this.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Comments