WATCH ABOVE: Behind the scenes at the Toronto Police College

Strictly speaking, the Taser that shot seven seconds of paralyzing electricity into Aron Firman’s chest, darts piercing bare skin for 14 minutes before they were removed, before CPR was performed, was only a “contributing factor” in the 27-year-old’s death.

That was the conclusion of a coroner’s jury three years after Aron died in police custody. He was pronounced dead at Collingwood General Hospital at 6:31 p.m., 55 minutes after a pair of officers confronted him in the backyard of Blue Mountain Residence, the group home where he was living.

Aron had schizophrenia. For years he’d been in and out of hospital, at times against his will. But changes to his medication months before his death helped give his life and his mental state a fragile stability. Until that day in June, when neighbours called police: He’d been “screaming” at a woman living in his group home, had pushed her out of her chair. He was “growling and flexing his muscles,” witnesses said.

Aron was sitting alone in the backyard, wearing jeans but no shirt, when police arrived. They spoke with him for about five minutes before one officer pulled out pepper spray and the other told Aron he was being arrested. Aron “leapt from his chair,” “fists clenched and flailing.” When one officer tried to grab him, he elbowed her in the face. Then the other officer Tasered him. Barbs in his bare chest, Aron tried to run, then fell.

He never got up.

“It was a tragedy,” says Aron’s dad Marcus Firman. Marcus knew what his son was like when he was off his meds or when his prescribed cocktail of antipsychotics lost their efficacy.

“Aron was a talker. He was not a fighter.”

It’s been five years since his death. Marcus still tears up when he reads an op-ed one of Aron’s high school friends submitted to Collingwood’s Enterprise-Bulletin.

“I will not remember him for his illness or for what has happened to him, or let it define who he was,” Meghan Sandberg wrote.

“To me he will always be ‘Firman.'”

Lawyers for Taser International were among those testifying at Aron Firman’s inquest. They contended, and the jury ultimately agreed, the primary cause of the cardiac arrhythmia that killed him was “excited delirium” – a condition not recognized by medical or psychiatric organizations but that’s frequently cited in the context of in-custody deaths – and schizophrenia.

The officer who Tasered Firman was cleared of wrongdoing.

Coroner’s jury and years of carefully couched legalese notwithstanding, Aron’s dad still sides with the forensic pathologist who examined his son, calling this an “index case” of Taser-related death.

“Without the taser he’d be alive today,” Marcus said.

“With better training of police he’d be alive today. Oh, for sure.”

Do police need more Tasers?

WATCH: Deputy Police Chief Mike Federico on Toronto Police’s pitch for more Tasers

Toronto Police are preparing to ask the city, and their oversight board, for about 170 new Tasers. That would increase the force’s total complement to more than 700 conducted energy weapons.

Do they need more? Are they properly using the ones they have now?

Depends whom you ask.

Deputy Chief Mike Federico says yes:

“There are plenty of times when officers have arrived on a situation, could have used a less lethal option in the form of a CEW, but because they’re limited in their ability … officers have had to use some other alternative.”

Police Services Board Chair Alok Mukherjee isn’t so sure.

“I don’t see a business case for it,” he said in an interview.

Nor is the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, or a lawyer who’s testified at inquests and represented Taser victims.

“It would be entirely inappropriate for there to be any increased deployment of Tasers,” lawyer Peter Rosenthal said in a submission to Justice Frank Iacobucci.

Tasers, also called Conducted Energy Weapons (CEWs) have been used by Canadian law enforcement since the late 1990s. There are close to 10,000 of them across the country.

Before their use is expanded to more front-line officers we wanted to get a better sense of how they’re used, when they’re used, whom they’re used on and what we know (and don’t know) about their effects.

Global News analyzed 600 pages of Taser use incident reports from the police force of Canada’s largest city. We spoke with officers who train Taser users, lawyers who’ve represented Taser victims, advocates for individuals with mental illness who are all too frequently on the receiving end of a stun gun’s barbs.

WATCH: Tasers as a ‘less lethal’ weapon

Read the series:

What we found from 594 pages of Taser incident reports

What happens to you when you’re Tasered

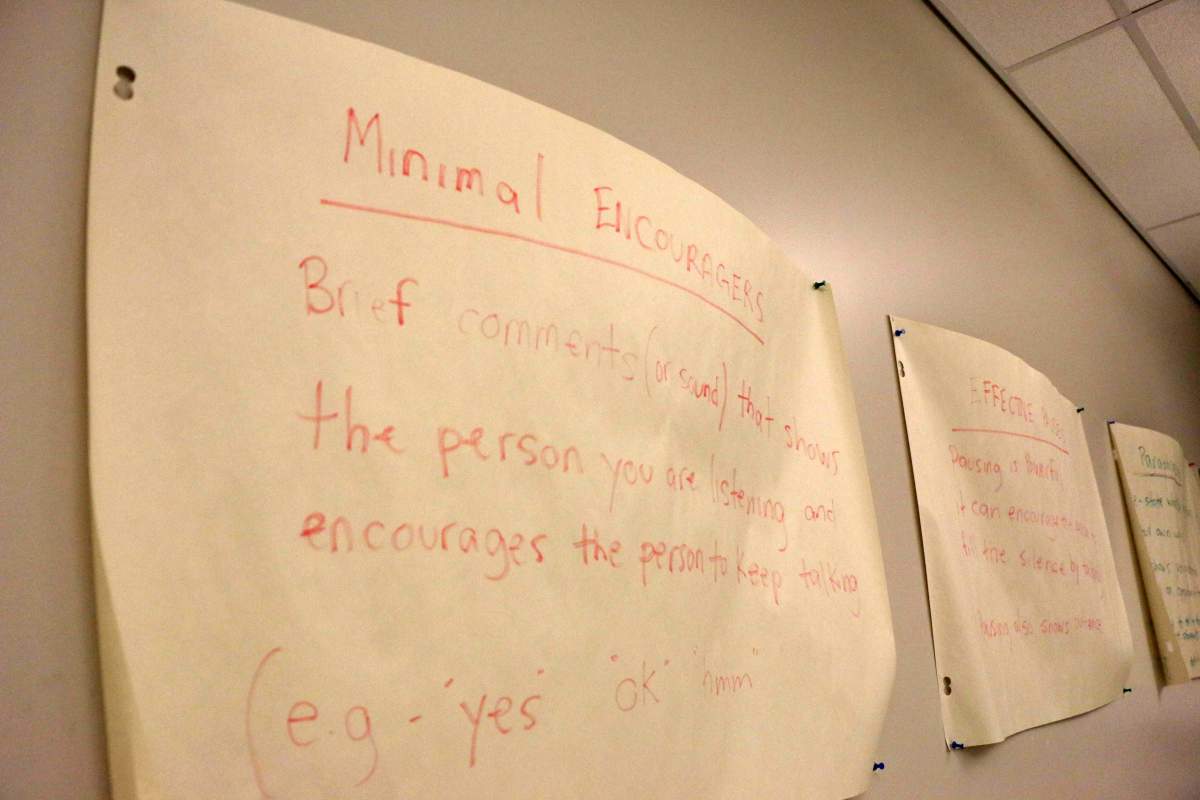

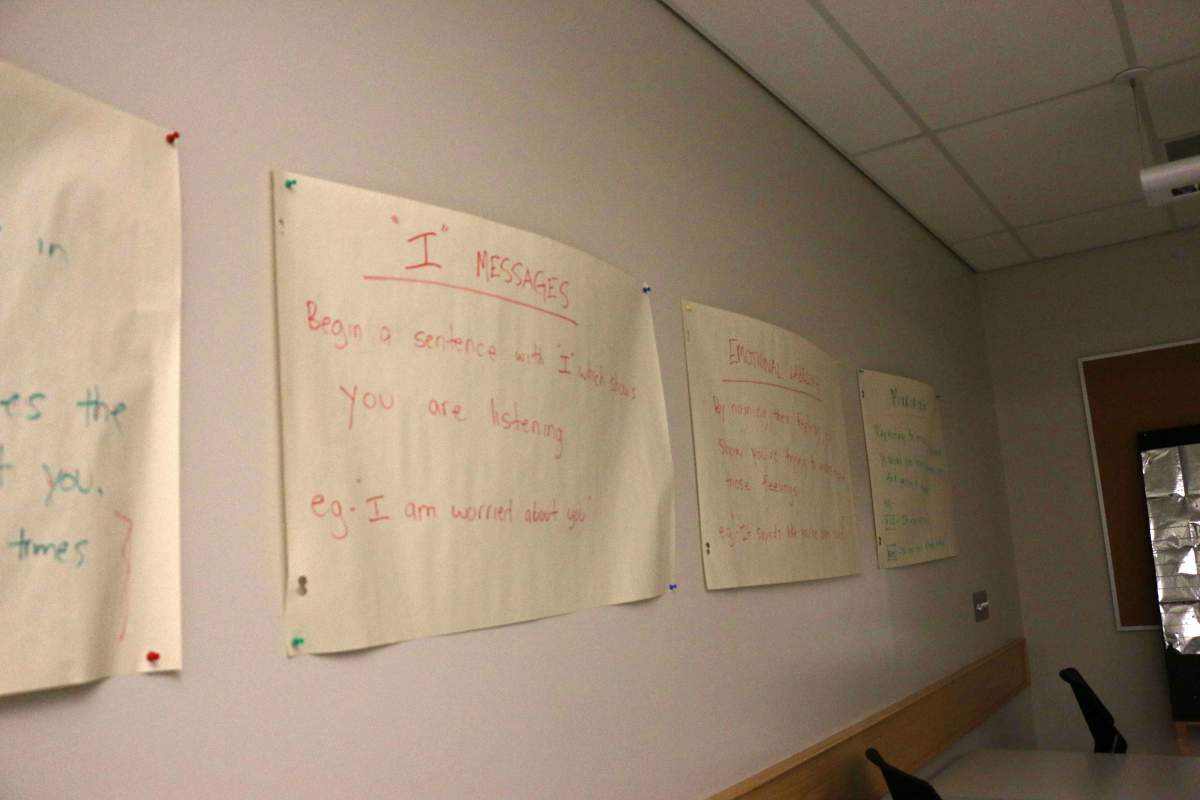

Psychiatrists in blue: How do you train cops to be better social workers?

Police forces across Canada encounter people with mental illness more than ever. But they’re still struggling to learn how best to de-escalate these encounters, how to keep them from becoming deadly.

The issue became particularly pertinent this week after police shot to death a man reportedly armed with a hammer in Toronto’s west end.

Last year, in the wake of the fatal streetcar shooting of Sammy Yatim, Justice Frank Iacobucci released a series of detailed recommendations for police in dealing with people in crisis. Among them was the suggestion to expand the use of Tasers, seen as presenting a less lethal alternative to firearms.

In the wake of more permissive provincial rules that allows front-line officers to carry them, multiple police forces have sought to expand Taser use to more of their officers.

Now Toronto Police are preparing a new proposal to deploy Tasers to “select” officers across the city.

“We need to continue to invest in police training, in sensitizing police officers, destigmatizing people’s conditions that gives rise to behaviour that police officers think is threatening. That includes emotionally disturbed people or mentally disordered people,” Deputy Federico said.

“On the other hand, we do believe that the availability of a less lethal force option in the form of a CEW can help police officers defuse situations safely.

“I’m quite confident the board will give this serious consideration when we present our proposal.”

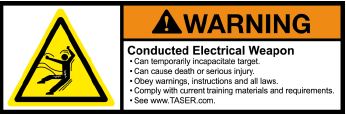

Tasers are touted as a “less lethal” option. Less lethal than a gun, that is. But even manufacturer Taser International admits in its safety warning that a Taser can cause “death or serious injury.”

As hundreds of pages of incident reports make clear, Tasers aren’t used as alternatives to firearms: Among the Taser deployments by the city’s police in 2013 and 2014, they’re overwhelmingly used on “emotionally disturbed persons” and people intoxicated by alcohol or drugs; they’re used on people attempting or threatening suicide; people visibly agitated and resisting police but who don’t pose an immediate threat to others.

Get breaking National news

And changes to provincial use-of-force guidelines for Tasers, including what to do in cases where someone loses consciousness after being Tasered, were never implemented after being recommended by the jury investigating Aron’s death.

Federico says officers get paramedics to the scene as soon as they can when a Taser’s deployed.

“An officer’s always got to be mindful of the person’s medical condition … regardless of whether the CEW is used. So the same standard applies.”

Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety is reviewing its use-of-force protocol. A Ministry spokesperson couldn’t say when that review will be complete.

“Have they learned anything? I would say not,” Marcus Firman said.

Toronto Police Board Chair Alok Mukherjee thinks Toronto Police use the Tasers they have appropriately – but they don’t need any more.

“I have never been in support of giving a Taser to every police officer,” he said.

“I do not believe there has been as much in-depth examination of all the potential risks as is necessary.”

That includes risks to pregnant women, older people, skinny people, children, people with heart problems or who’ve consumed alcohol or drugs or over-exerted themselves or who are psychologically or emotionally distraught.

And, Mukherjee adds, there’s no evidence police need extra stun guns — no flood of unnecessary use of firearms where a Taser would suffice, no brutal baton beatdowns that could have been avoided with the aid of Taser-facilitated neuromuscular incapacitation.

“What is the business case for tasers? … In my mind, the number of tasers we have is justified. The utilization of those Tasers does not justify expansion.”

Instead, he says, police need better, more frequent training in how to defuse situations.

“I’m not saying ‘No Tasers,’ but very well trained, limited number of personnel across the police service should have Tasers to back up when all else fails.

“My fear is that if we don’t do that, we will run the risk of the Taser being used more often than negotiating skills, engagement, learning how to disengage, how to bring things down from a state of tension.”

Mukherjee wants to see Toronto cops trained to be social workers as much as law-enforcement. That includes exposing them early in training to people with mental illness, people who’ve been abused — the kind of vulnerable individuals frontline officers interact with most.

“Good policing involves using your brain and your mouth and your judgment more than using hardware,” Mukherjee said.

“A great deal of time is spent by police officers helping those people. Preventing victimization. The more we can open their hearts and minds to what it is to be in that situation, I think, the more understanding they will be, to not be fearful of those people but to see them as human beings in difficulty.”

READ MORE: Re-imagining Toronto cops

A ‘less lethal’ weapon

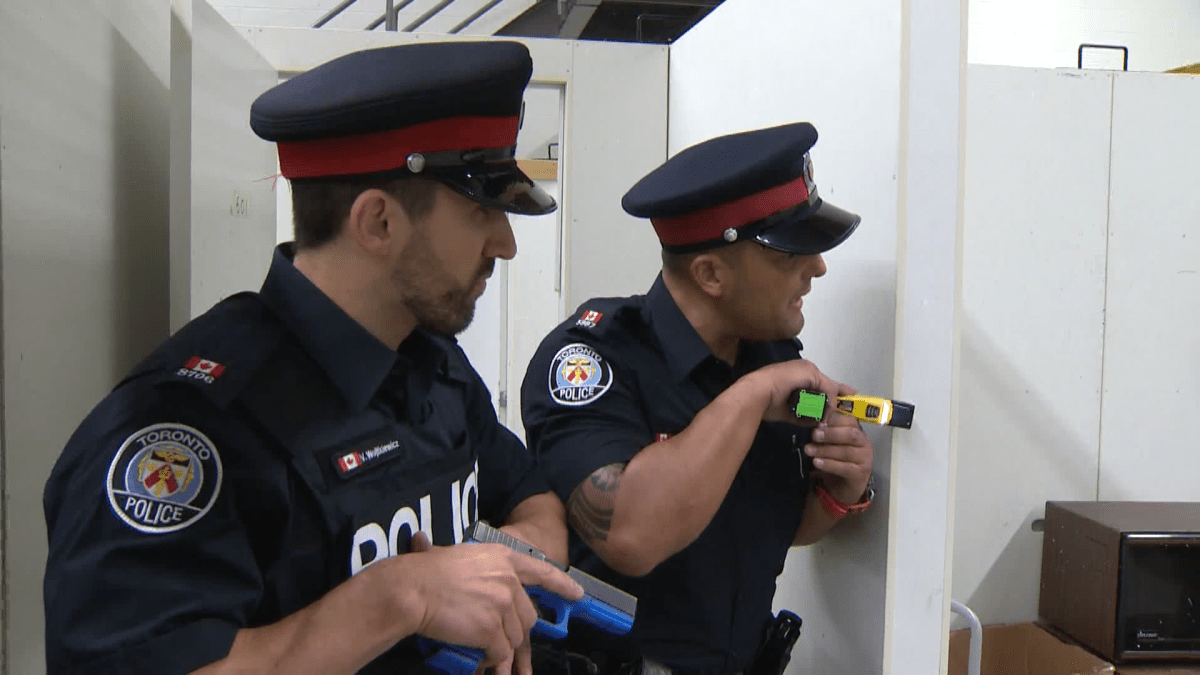

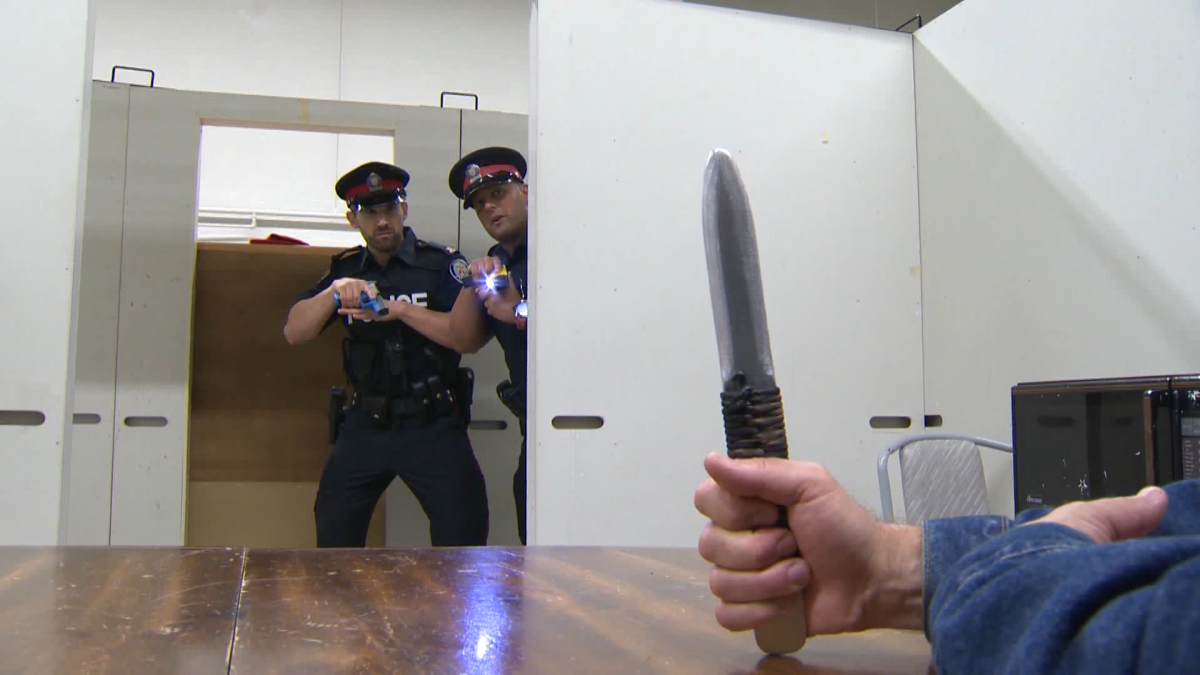

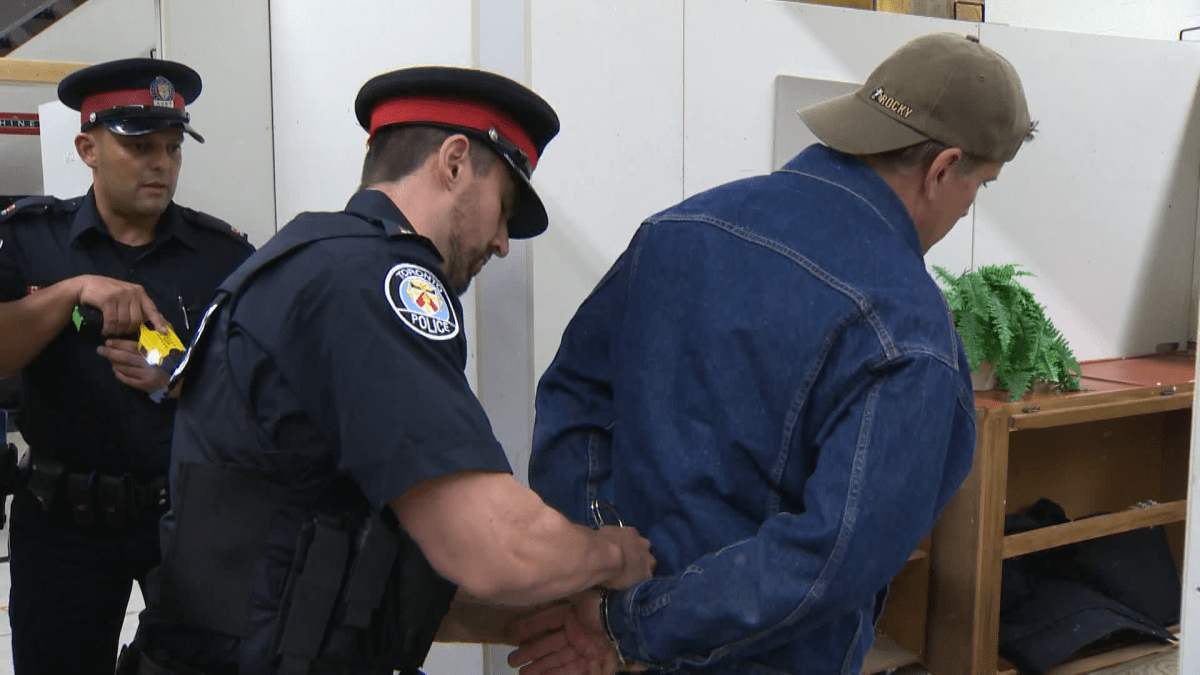

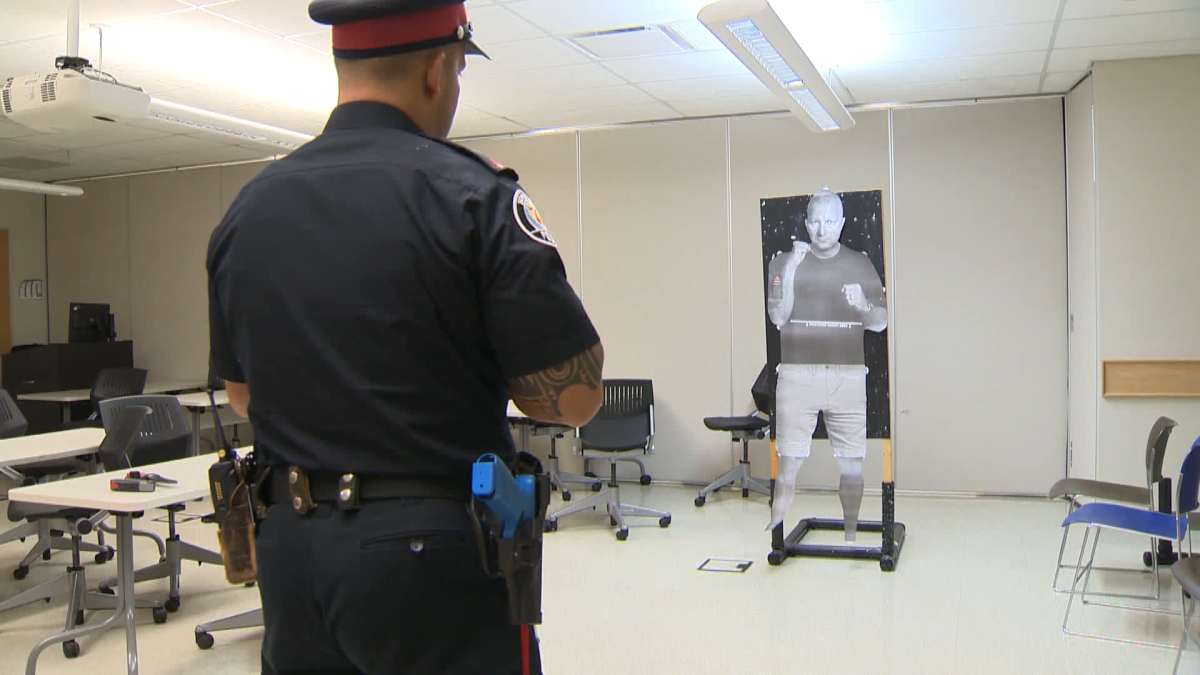

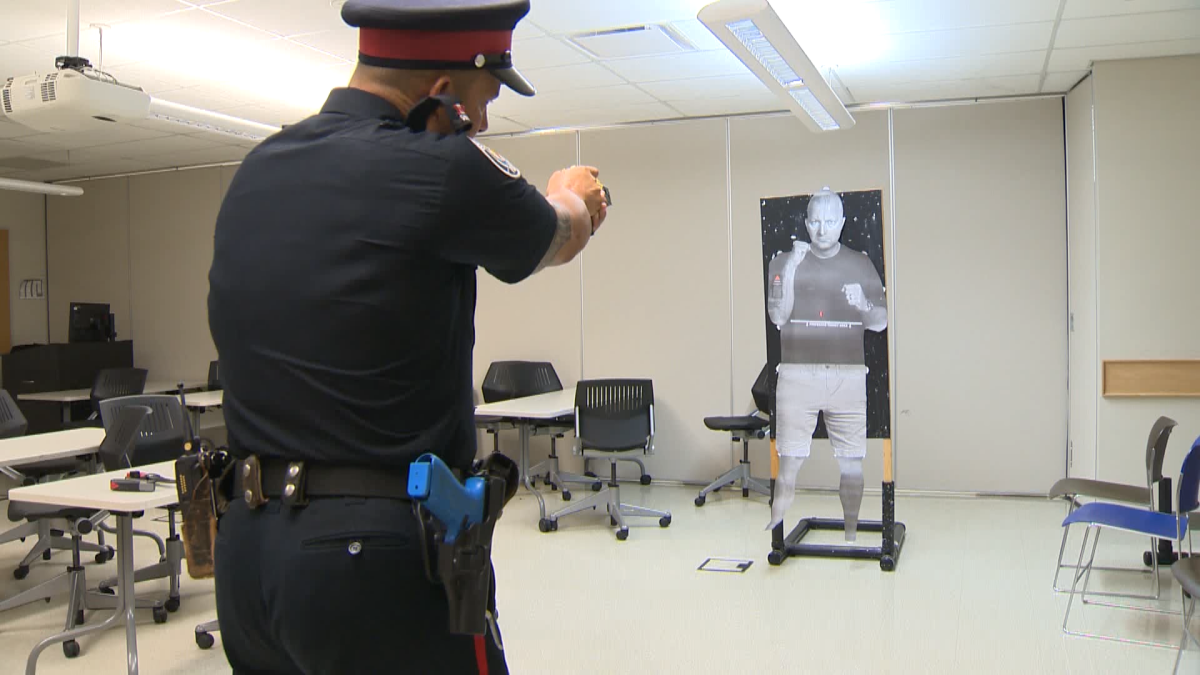

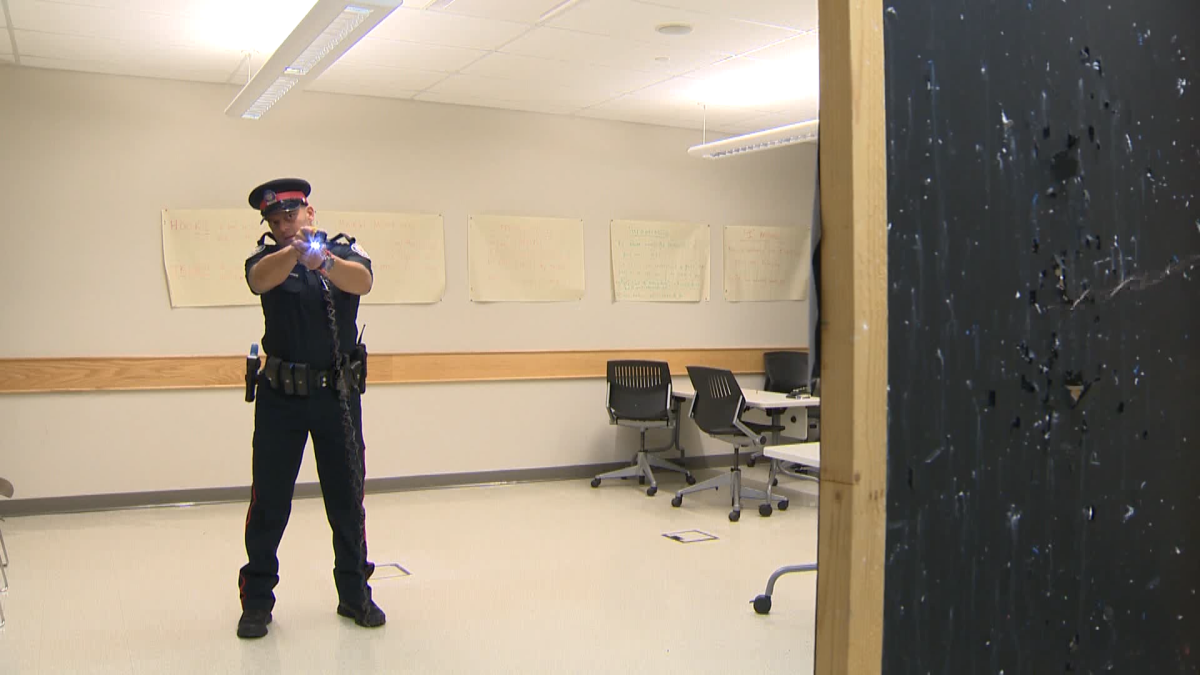

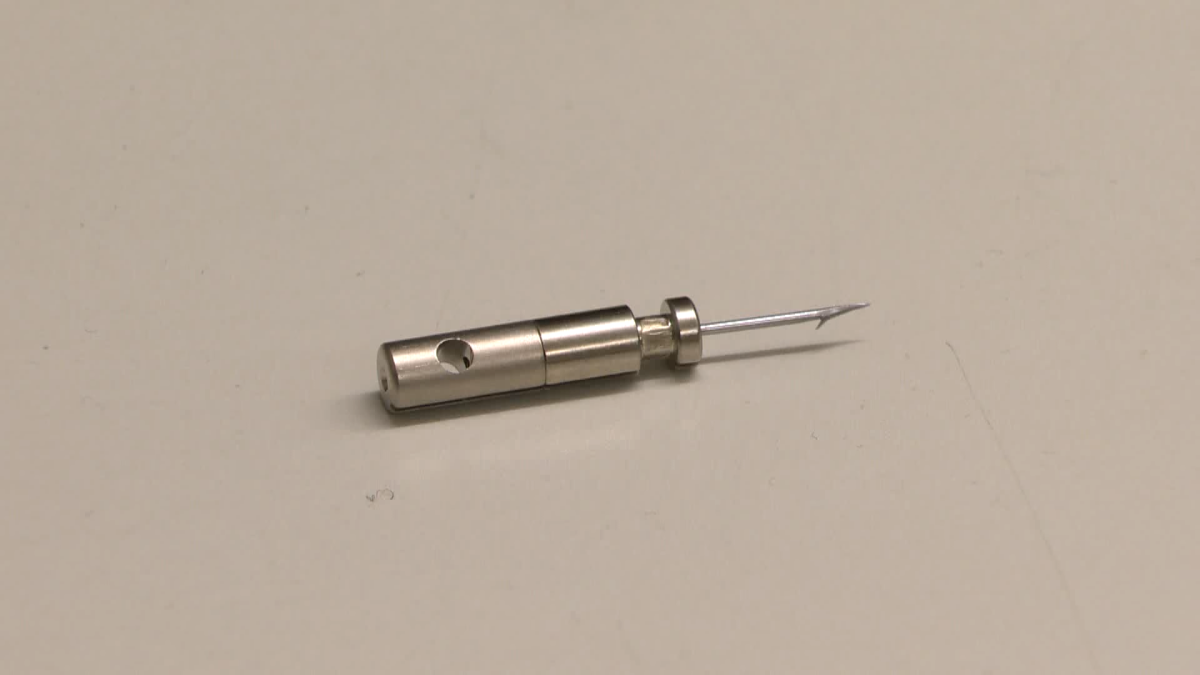

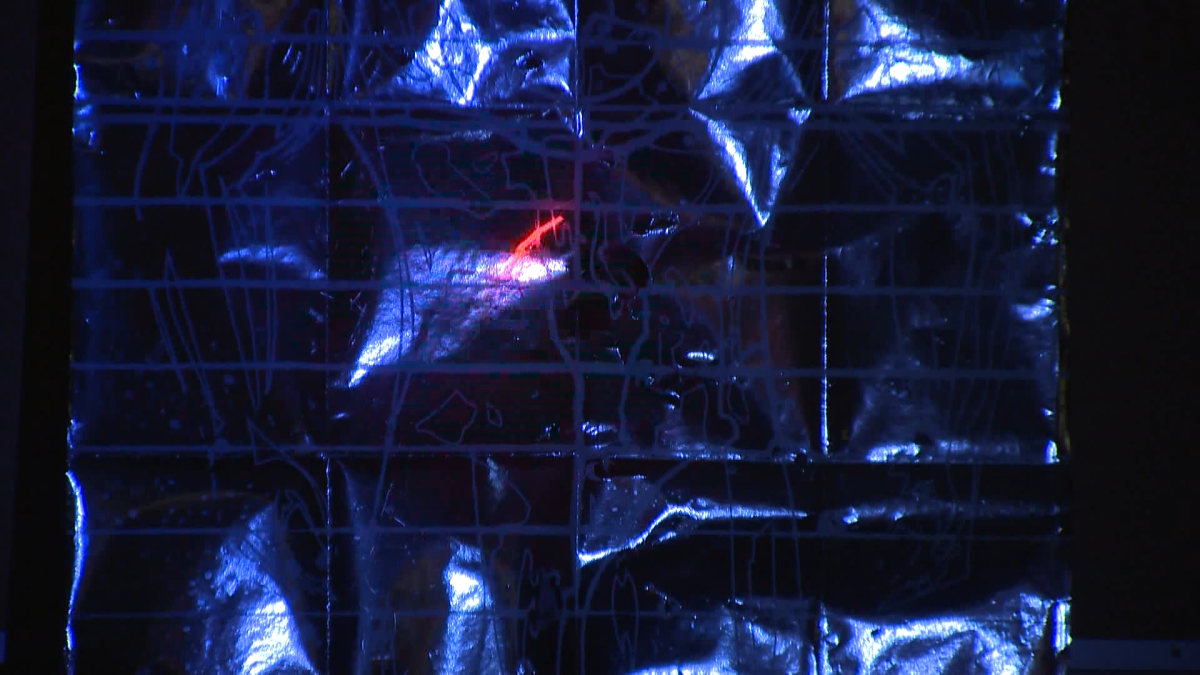

Taser deployment is louder than you’d think — a stick-snapping earsplitting crack as twin barbed probes, like straightened fish hooks, fly out at high speed, embedding themselves in a human body (or foil-and-cardboard target, as the case may be). Then an electric rattlesnake crackling for the duration of the current’s cycle.

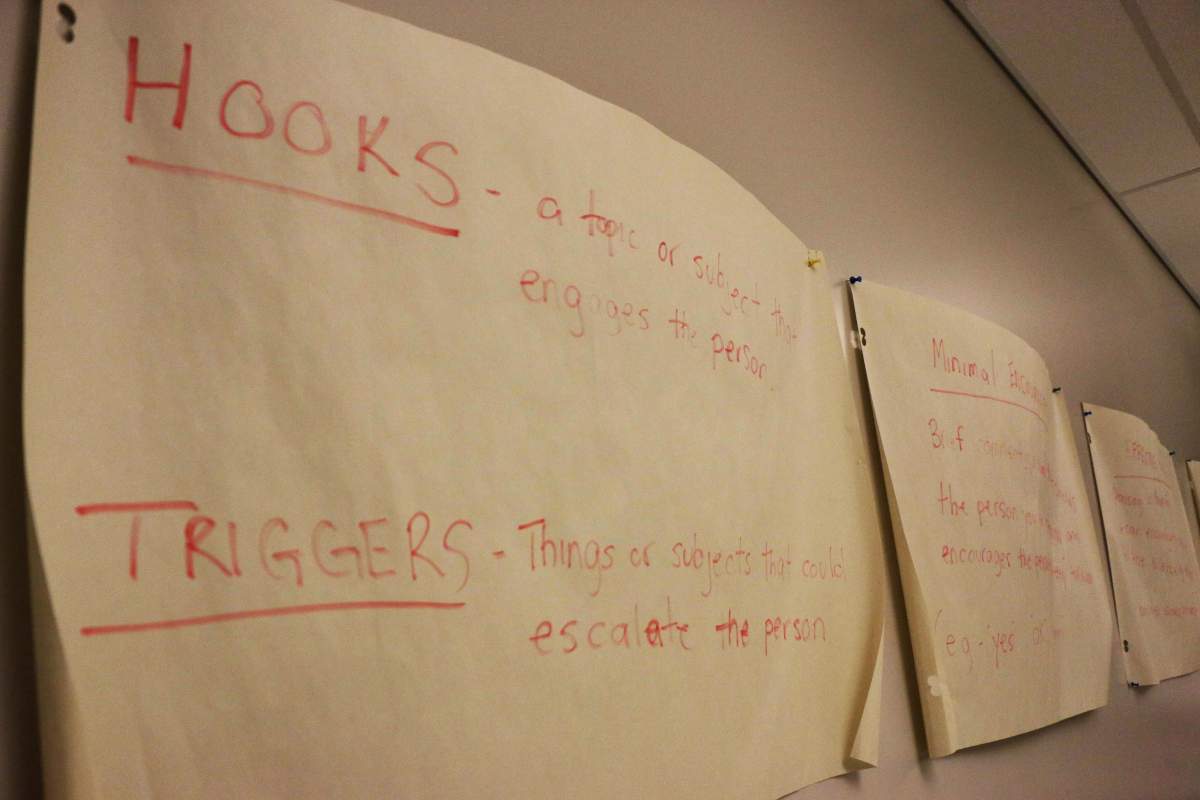

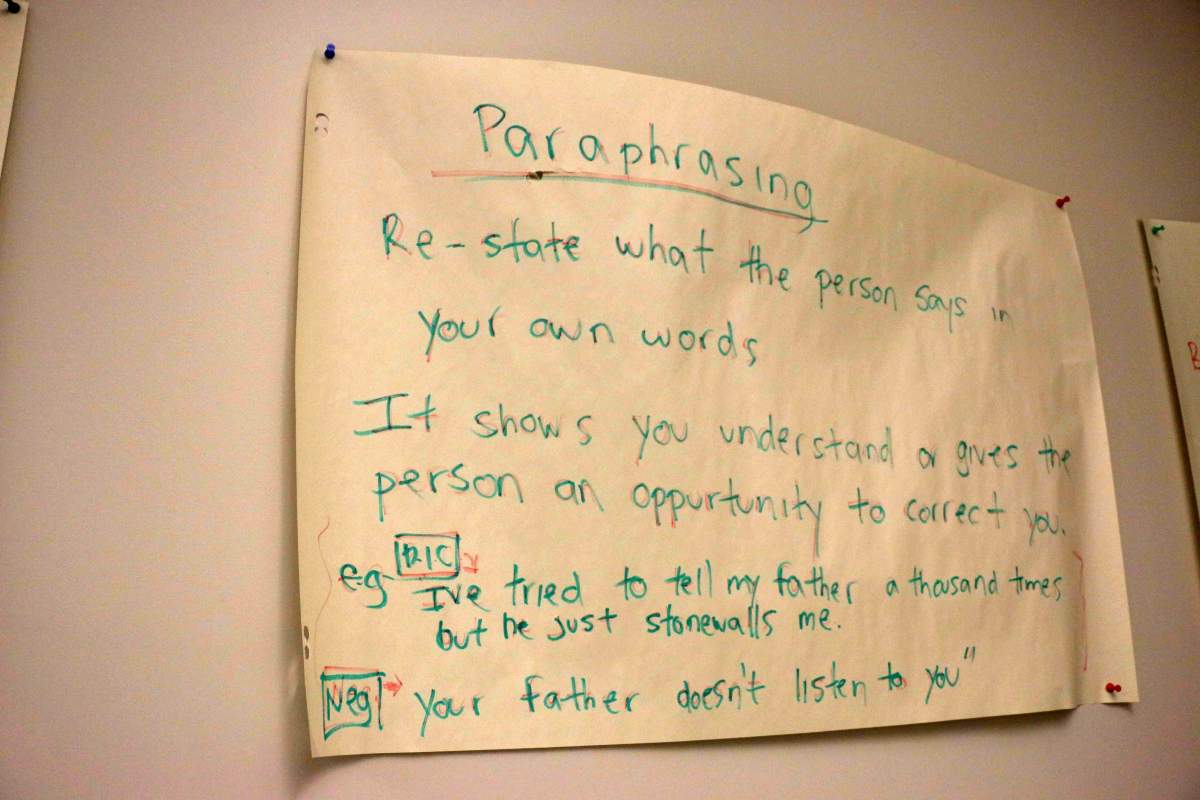

Global News visited Toronto’s Police College in Etobicoke to get a sense of how officers are trained to use Conducted Energy Weapons.

In Toronto, supervising officers and Emergency Task Force members get Tasers, although the force plans to expand that. Initial 12-hour training (followed up with annual four-hour refresher courses) covers how the stun guns work, the way they stop a person cold for several seconds, when officers should use them — and how to ensure they use them as seldom as possible.

“The CEW is not a weapon of convenience. It’s a weapon of necessity,” says Staff Sgt. David Gillis.

WATCH: Tasers on the Use-of-Force continuum

Gillis is in charge of firearms and Conductive Energy Weapon training at the Toronto Police College. He coordinates, designs and approves armament training modules.

A Taser is an important part of certain officers’ use-of-force arsenal, he says. But “we use it very rarely.”

“If you want to use it in full deployment or drive-stun mode, it has to be someone who’s exhibiting assaultive behaviour, threatening assaultive behaviour, or at risk of causing imminent, serious bodily harm or death. That also means suicidal actions.”

Tasering suicidal people, even if they don’t pose a danger to anyone else, is allowed under Ontario’s use-of-force policy.

WATCH: How Toronto Police use Tasers

Most of the time, Gillis said, “we talk, talk and talk.” Officers are encouraged to use their Tasers more as a display of force than as a painful, incapacitating weapon, if they take them out at all.

But sometimes, Gillis said, a Taser is “the safest way” to deal with a tense situation.

“We have to respond to someone’s behaviour,” he said.

“I review all the use-of-force reports, all the conducted energy weapon reports. And I’ve had officers say, ‘If I didn’t have a CEW, I would have had to use a firearm.'” But Gillis acknowledged most cases of Taser use in Toronto aren’t cases where officers would have used a gun.

WATCH: ‘Nothing is ever non-lethal’

No one has suffered a “serious injury” after being Tasered by Toronto police, he said. But can it be lethal?

“Nothing’s non-lethal,” Gillis said.

“I can strike you with a baton, you could die. I could strike you with my fist, you could die.”

Gillis has been hit with a Taser — twice. “It is painful. … Everything just locks right up.”

Emergency Task Force officers get Tasered as part of their training, he said. Partly so they get a sense of how long a subject’s incapacitated by it.

And partly so they keep in mind how it feels before they use it.

“I think it’ll make the officers use it more judiciously.”

Gallery: Click through for photos of a Taser training at Toronto Police College

‘It’s better for police not to have Tasers’

Lawyer Peter Rosenthal tends to represent people on the other side of police encounters. He’s testified in court and at inquests and has come to a contrarian conclusion: It isn’t worth the risk to give officers Tasers; the scenarios in which they’re really the safest option are too rare, the temptation to use it as a tool of convenience too great.

“You can design scenarios when they might be useful, but they’re so rare, in my opinion, that the danger of having Tasers and having them used in all sorts of other situations isn’t worth it, on balance,” he said.

“It’s better for police not to have Tasers. … It’s not a useful weapon.”

Rosenthal has represented people who’ve taken police to court over Tasering incidents. But the cases were settled and are now protected by confidentiality clauses.

“It’s a very traumatic experience. It could very easily be a fatal experience, and can cause other injuries,” he said.

“If a Taser works properly the victim falls to the ground … without any protection. You can smash your head on a curb. You can break an arm.”

Rosenthal doesn’t buy arguments that providing more officers with Tasers will mean fewer people get shot or hurt.

“If they get more Tasers, more people will be Tased. And it will not cut down on the number of people killed, but it will lead to more people suffering the kinds of injuries Tasers cause.”

Canadian Civil Liberties Association legal counsel Sukanya Pillay wants to see tighter rules around Taser use. For starters, she says, Ontario could adopt recommendations from the Braidwood inquiry into the 2007 death of Polish immigrant Robert Dziekanski, who died after being hit with a Taser at Vancouver’s airport.

That includes restricting Taser use to cases where a person is causing or definitely about to cause bodily harm, and where other attempts at de-escalation have been tried and failed. Braidwood’s recommendations also include more rapid and stringent health precautions taken and better training for dealing with people in crisis.

B.C. RCMP adopted the recommendations in 2009. Ontario’s police forces have not, Pillay notes.

“We have a lesser standard.”

Rather than invest in more Tasers at thousands of dollars a pop, Pillay would rather see police spend more money on training, especially when it comes to dealing with people in crisis or with mental illness.

“They need truly effective training that focuses on de-escalating intense situations, that recognizes the physcial cues displayed by an individual in crisis can be different from an individual who is quote-unquote ‘typical.'”

The coroner’s jury investigating Aron Firman’s death recommended Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services change the way it collects information about Taser deployments, and that police change their training and guidelines for Taser use — including amending practices so that police remove the barbed probes from a Taser and provide CPR to unconscious individuals as soon as possible, rather than wait for paramedics to arrive.

Those policing practices haven’t been changed, two years after the report was issued. A spokesperson for Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services noted the new model of Tasers, being rolled out to officers over the next several months, are designed to be safer and collect more data.

At the same time, Taser training increased over the past few years afrom eight to 12 hours. “This is all part of our government’s plan to build safer communities for all Ontarians.”

Pillay argues stricter rules are needed.

“In a healthy democratic society, the people entrust the police with the duty to keep them safe and the responsibility of carrying weapons,” she said.

“How those less-lethal weapons are used becomes a very important question.”

Comments