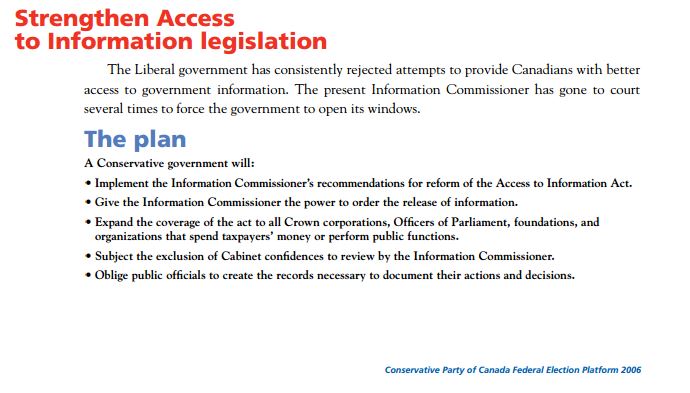

Many of Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault’s recommendations to fix Canada’s strained and aging access-to-information system will be familiar to Prime Minister Stephen Harper: They were part of his platform nine years ago.

The 2006 Tory platform pledged to strengthen access to information legislation but that plan appears to have lost its urgency now that the party’s in power. Speaking to reporters after releasing her report on federal access to information, Legault said she’s brought up many of these issues with the federal Conservative government before but has gotten no response.

The Access to Information Act came into force the year Rick Hansen launched his Man In Motion tour, Mikhail Gorbachev became Soviet leader, New Coke was launched and swiftly panned.

Reform is long overdue, Legault said.

“We will not be able to achieve an open-by-default government without really modifying the access to information regime,” she said.

A system meant to serve all Canadians has become bogged down and often unnavigable even for those who use it most (including businesses, lobbyists and journalists).

HOUNDS OF PARLIAMENT: Read our profile of Suzanne Legault

Treasury Board President Tony Clement, who oversees the access to information regime, has called Canada’s government the most open ever and cited the volume of documents it releases and requests it deals with as proof they’re becoming ever-more transparent.

Legault doesn’t buy it.

Get breaking National news

“The volume of pages disclosed in response to an access-to-information request is not a sign of a transparent government.”

And the growing number of access requests being filed annually could indicate that’s becoming the only way to get basic public information, she said.

(While some Tory MPs have argued the access-to-information system has become too much of a financial burden and requesters should be made to pay more, many have pointed out that making more information public by default would save everyone the time and resources put into requesting it.)

READ MORE: Feds dispute Canada’s low global access-to-information ranking

Legault’s recommendations would put all government institutions under one access umbrella; narrow the reasons information officers can cite in denying access, limit the amount of time they can give themselves and impose a tougher burden of proof to officials arguing some records need to be kept secret.

Crucially, she’d codify the “duty to document” – a requirement to record government deliberations and decisions (so if you ask for something, it’ll actually be there) that’s now in policy, but not law.

She’d give her office the power to enforce the rules, check up on government and compel it to release documents.

“The duty to document is absolutely essential. And it must come with sanctions,” Legault said.

“Instead of the Act moving the government forward to a culture of openness, it seems to have moved us toward a culture of secrecy.”

You can read all 85 of Legault’s recommendations here.

Among her key points:

1) Access more information

“The current act contains so many exclusions and exemptions, it has become a how-to guide to deny disclosure.”

Your right to information doesn’t cover key parts of Canadian government – including the Prime Minister’s office, ministers, the House of Commons and the Senate.

When the Senate was rocked by scandal, Canadians had to fight to figure out what was going on because the Senate Ethics Commissioner was exempt from access-to-information rules.

Legault would change that. She’d also raise the threshold for information government bodies refuse to release.

Right now, everything considered “advice to the minister” is exempt. That could include virtually anything. Officials should have to prove the potential harm releasing that kind of advice would cause, Legault says. And once a pertinent decision’s been made or several years have passed, she says the advice exemption should no longer count.

2) Access information sooner

So you’ve filed a federal access-to-information request. The government agency has to respond within 30 days — with a key caveat: If they need more time, they can just tell you they’re giving themselves an extension.

That extension can be anywhere from 60 days to 180 days or more, and could come in the form of cascading extension letters, each adding a month or two to the time needed to find or extract or redact the information you’ve requested. (Then there’s the request National Defence said it would need more than 1,110 days to complete.)

But a lot of these extensions are frivolous, Legault says. She says the system has created a culture of delay — especially troublesome in a time when information travels in however many nanoseconds it takes to press the “send” or “retweet” button.

The Federal Court of Appeal agrees: It stated that timely access to information is a key element to the right of access.

To crack down on unnecessary delays and ensure the extra time government information officials give themselves is “rigorous, logical and supportable,” she recommends any extensions over 60 days require her permission.

3) Access watchdog gets teeth

It’s tough to safeguard Canadians’ right to government information when you can’t make anyone do anything.

Right now the Information Commissioner can recommend information be released, but if a government institution says no, she has to take them to court, where they can bring new information forward proving their point.

If she can order the release of documents it’ll require the government body in question to convince her the refusal to release info is justified. If she isn’t convinced, she can compel the information’s release.

The new rules would also let her audit government to ensure compliance and sign off not only on changes to the Act but on extensions to individual requests that would take longer than six months.

Of course, because Legault doesn’t have any of these powers now, all her recommendations are only that: She needs Parliament’s support to make them happen.

Comments