We’ve been inundated with the stories — personal, frank, harrowing — of sexual assault survivors since publishing this story about how difficult it is to get justice for rape.

Among the people we spoke with were survivors who wanted to go public with the abuse they suffered and the way they feel Canada’s court system failed them, and wanted to put their names to their stories.

But because of rules imposed by the same court system that in so many cases fails the victims of sexual violence, we believe their names remain under publication ban – ostensibly for their own protection – long after cases are closed or alleged abusers no longer living.

We wish we could honour the wishes of these individuals to be named. Out of an abundance of caution, we have not.

Please note: The content below may be disturbing and triggering for some people.

Jane has a timeline, written in pen on graphing paper, of the years she spent living with her serial rapist.

First what she calls the ‘Honeymoon Phase,’ when she was swept off her feet by his flattering charm, convinced to move in after a few short months of dating.

Then the rape — the first one — three weeks after she moved in.

“It was like I was hit sideways by a bus. I went into shock. And then denial.”

Then five years of torment, of denial and self-blame, of making excuses to explain away the behaviour of the man she thought she loved.

She says she conceived their child during one such attack. Multiple times, after the child was born, he assaulted her while their baby boy slept beside her in bed. He spied on her online messaging, sent emails from her account, convinced her she was stupid and at fault for his repeated sexual assaults. He threatened to “destroy” her, to publicize videos and photos he’d taken of her in sexual situations.

After he grabbed her by the hair and smashed her head into a door, she went with a swelling forehead goose egg to the Toronto police.

He was arrested and charged. And Jane escaped, but she says she got no justice.

READ MORE: Why Canada still has a long way to go in tackling domestic abuse

She found herself on the stand in pre-trial hearings, being cross-examined by a defence lawyer as though she was the one on trial.

“I was interrogated,” she said.

“They were going after my mental health. … It was like, I’m messed up, I’m unstable.”

She was forced to watch as the videos her abuser had made of them having consensual sex were shown to a courtroom, as though consenting once makes past and future rape inconceivable. (Under Canadian law, it does not: Consent must be affirmative and ongoing.)

The charges were stayed.

READ MORE: Nearly a quarter of Ontarians still blame victims of domestic abuse

Jane now lives in a Toronto apartment with her son Joseph, who’s almost six.

“In his mind he thinks, ‘Daddy doesn’t live with Mommy any more because Daddy was hurting Mommy.’ …

“A five-year-old child understands, but the legal system doesn’t.”

She negotiates ongoing custody arrangements with Joseph’s father. The irony does not escape her: “My son is having sleepovers at my rapist’s house.”

Jane’s doing better. But the ordeal has soured her for good on Canada’s court system.

“The system is not made for justice,” she said.

Get weekly health news

“If any of my female friends were in my situation, I would say, ‘Don’t go to the police. Don’t even bother.’ Because what I went through was horrendous. It was devastating.”

READ MORE: Why don’t women report rape? Because most get no justice when they do

Most sexual assailants don’t fit the stereotype of strangers hiding in bushes, walking behind you on darkened sidewalks, on lonely subway platforms. They’re colleagues and teachers; spouses, step-parents, caretakers and friends.

An Ipsos poll conducted for Global News found 30 per cent of respondents who’d been sexually assaulted had been abused by a family member; an additional 47 per cent had been sexually assaulted by someone they knew.

The power dynamics behind these close relationships can make sexual assaults harder to report, pursue or stop; violated trust can also fuel the false conviction a victim somehow brought this on themselves: How could someone so trusted do something so vile?

The same poll found that 82 per cent of women who were victims of sexual assault didn’t report incidents to police. It found that of those who did, 39 per cent ended up feeling “devastated” about the outcome, 37 per cent felt “abandoned” and another 37 per cent felt “distraught.”

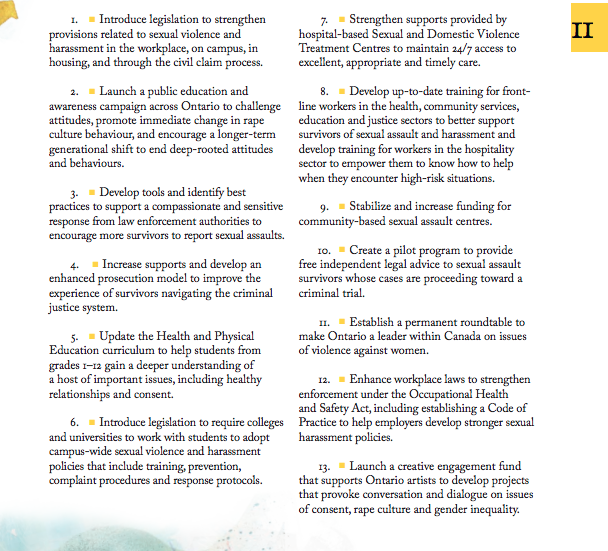

Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne unveiled a strategy to fight sexual assault on Friday.

Its 13 points include:

- more funding for rape crisis centres;

- training for front-line workers, including the health and justice sectors;

- legal assistance for victims whose cases go to criminal trial;

- redefining workplace sexual harassment;

- the requirement that post-secondary institutions address the issue head-on with strategies crafted in concert with students.

The legislation won’t be tabled until this fall, however.

Wynne attributed the continuing pervasiveness of sexual assault to an ingrained culture of misogyny, noting that this is something she and her friends were trying to confront 40 years ago.

To the province’s survivors of sexual assault, most of whom will never report their rapes to police, Wynne said,

“We see you. We acknowledge what happened to you is wrong. And we stand with you.”

TJ’s story

In our discussions with sources who responded to our request, we didn’t only hear from women. Men also reported nightmarish experiences of sexual assault. While the stories differed, the wall they ran into when they sought justice was largely the same.

TJ was six years old. The man was his karate coach, a man he and his brother looked up to as a father figure, who their mother knew and trusted to babysit when one of them was home sick and she had to work.

It started on one such sick day, when innocent-seeming horsing around led to the man pulling off TJ’s pyjama pants, holding him down, and assaulting him.

For two years TJ told no one – convinced no one would believe him and believing the threat he’d endanger his mom and brother if he told.

And when he finally told his mother, who went to the police, not much happened: The man agreed to psychiatric counselling, TJ says, and that was it.

It was the first in a litany of sexual abuse as TJ, a troubled and vulnerable kid, bounced from one children’s aid home to another. In each case, the men who grabbed and fondled him were in positions of authority.

TJ got out and on the streets as soon as he could. Fell into cycles of addiction. Was in and out of jail, mostly for petty theft and assault.

Then he had a son of his own. And that changed everything.

“I’m now responsible for another life other than my own. And I don’t want my son to go through another thing that I went through.”

Years later, married and with a farm near Simcoe, Ont., TJ went to the cops and laid it all out. All the names, all the abuses. In many cases, he says, the men who’d sexually assaulted him had strings of other victims.

But not much happened, he says.

“Being a victim, you want your feeling to be validated. You want someone to say, ‘I understand what was done to you, and it was wrong.’

“There’s so much taken from you. And you look for justice.”

Men make up the minority of survivors of sexual assault. And TJ knows most of them will never talk about their experience.

“It’s a shame thing. … And if men don’t hear other men admit it, they’re going to live with it for how long? And it destroys you inside.”

In his own case, he said, it took years before he could tell someone the whole story.

“I needed to know it wasn’t my fault, and I could say what happened.”

Marie’s story

Marie, for her part, is enraged how little has changed since she was a little girl.

The Edmonton resident was 9, her younger sisters 7 and 5 years old, when their step-father began sexually abusing them.

“He would spit on our bottoms and lick it up.”

It was no secret: Their mother knew; so did the neighbours, who called the police about the screaming and yelling next door. The police knew, she said, and so did their teachers.

“People would call the police, they would come to our house and bring us back a few hours later.”

Years later, her younger sister told a psychologist about the abuse, and the psychologist took the case to the police.

When their stepfather went to court he was found guilty of three counts of sexual assault, she says, and given a day in jail and a $1,500 fine.

“We went through the whole court process and it did nothing for us. Absolutely nothing.”

Marie and her sisters got a lifetime of trauma. She still takes medication for the herpes she says she contracted through the abuse. But she considers herself lucky: She’s been well enough to work.

“People need to hear it. People need to be aware,” she said.

“It’s so frustrating, being victimized for so many years, starting at such a young age, and to find out things still aren’t done. … Women are still going through this horrible, horrible thing.”

If you’ve been assaulted and are looking for resources outside the justice system, try the Canadian Association of Sexual Assault Centres.

Exclusive Global News Ipsos Reid polls are protected by copyright. The information and/or data may only be rebroadcast or republished with full and proper credit and attribution to “Global News Ipsos Reid.” This poll was conducted between Jan. 17 and Jan. 23, with a sample of 2,150 Canadian women ages 18+ via the Ipsos I-Say online panel. It is accurate to within 2.4 percentage points 19 times out of 20.

Comments