VANCOUVER – The failure of Vancouver police and the RCMP to properly investigate reports of women disappearing from the Downtown Eastside has left both forces with the blood of Robert Pickton’s victims on their hands, the lawyer for many of those women’s families said Tuesday during the first day of a public inquiry.

Cameron Ward pointed to a series of missteps in the years preceding Pickton’s arrest in 2002 that he said allowed Pickton to continue killing sex workers, even after he was accused of trying to kill a prostitute and identified by tipsters as someone who was preying on women.

“They (the families) believe the authorities are culpable in the deaths of over a dozen women because the authorities’ negligence allowed Pickton to literally get away with murder for more than five years,” Ward, who represents the families of 18 of Pickton’s victims, said during his opening statement at the inquiry.

“Make no mistake about it: Our clients believe that the VPD, the RCMP and the Criminal Justice Branch have the blood of their loved ones on their hands.”

The inquiry is examining why police failed to catch Pickton in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and why prosecutors declined to charge him with attempted murder after an attack on a sex worker in 1997.

Pickton was arrested in 2002 and eventually convicted of six murders, but boasted of killing as many as 49 women. He lost his final appeal last year, setting the stage for the provincial inquiry.

Ward told Commissioner Wally Oppal that he will spend the hearings attempting to show that Vancouver police and the RCMP failed to take reports of missing women seriously, either because of ignorance, incompetence or prejudice.

And he said that failure was compounded after the alleged attempted murder in 1997. Ward said that was followed by several years of police investigations in which the forces brushed off public tips, failed to share information, and even declined Pickton’s own offer to have officers search his farm.

Get daily National news

During the next five years, Pickton killed more than a dozen women. The remains or DNA of 33 women were eventually found on his farm.

Many of the problems with the police investigations are known, primarily through an internal Vancouver Police Department report released last year.

The inquiry’s job will be to determine precisely what happened – and, more importantly, why.

Ward offered his own answer.

“We expect that the evidence brought before this inquiry will reveal that the police, to the extent that they even noticed, were full of disdain and contempt for the missing women and their families,” said Ward.

“The police – and most of the rest of society, if the truth be told – probably couldn’t have cared less what happened to these women.”

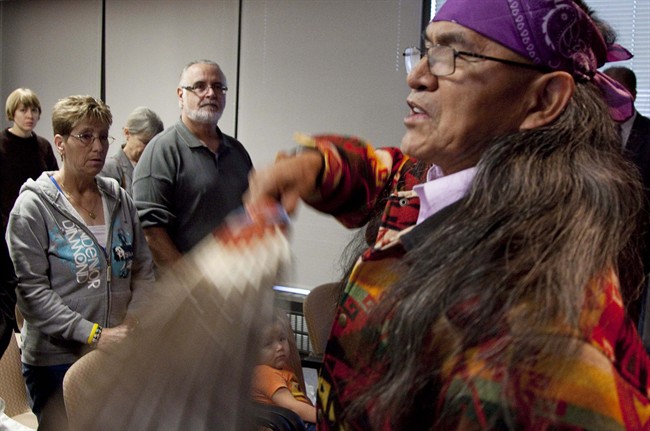

The first day opened with an aboriginal blessing from a Squamish First Nation elder, who performed much of the ceremony in front of a poster displaying the photos of Pickton’s victims before he draped a blanket around commissioner Oppal.

The hearings are expected to stretch on for months, and Oppal’s final report, which will attempt to explain what went wrong and make recommendations for the future, won’t be released for some time after that.

With several families of Pickton’s victims in the audience, Oppal opened the inquiry by telling them his goal is to determine if police and the justice system wrote off their daughters, sisters and mothers.

Pickton hunted for victims in a blighted neighbourhood that is often referred to as Canada’s poorest postal code, and the women he killed were among its drug-addicted sex workers, many of whom were aboriginal.

Oppal said those women nonetheless deserved to be protected by police and the law.

“They were the most vulnerable to violence, including sexual violence, and to murder,” said Oppal.

“We must ask ourselves: ‘Is it acceptable that we allowed our most vulnerable to disappear, to be murdered?’ The question is upsetting. It challenges our fundamental values. We say that each one of us is equal, each one of us is worthy of the same protection from violence. But is it true?”

Cynthia Cardinal, whose sister Georgina Papin was among the six women Pickton was convicted of killing, said she wants to know why her sister and so many women like her were neglected by the police. Papin disappeared in March 1999.

“It’s very disturbing, considering when they knew about all this. My sister could still be alive today had they investigated in ’98 and taken it seriously, all the tips that came in,” Cardinal told reporters outside the hearing room.

“I hope it (the inquiry) can inspire change that nobody has to go through this again, and it will be investigated more and that they take all tips seriously.”

As the hearings started, the chants and drums of dozens of protesters gathered in the streets below could be heard inside the courtroom.

The demonstrators were angry over the provincial government’s decision not to fund more than a dozen non-profit advocacy groups that were granted standing at the hearings. Most have withdrawn, saying they can’t afford to pay for lawyers on their own.

The list of groups that have quit grew yet again Tuesday, as the Assembly of First Nations and a coalition of groups that help sex workers formally bowed out.

“I think it will have marginal value, we have no faith in the integrity of this process,” said Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, which has also withdrawn.

“It’s absolutely ludicrous that these women, who are the victims of monsters like Mr. Pickton, continue to be ignored, continue to be denied justice. It’s an absolute outrage.”

Oppal is also conducting a less-formal set of hearings known as a study commission to examine broader issues surrounding missing women, including an area of northern B.C. known as the Highway of Tears.

Comments