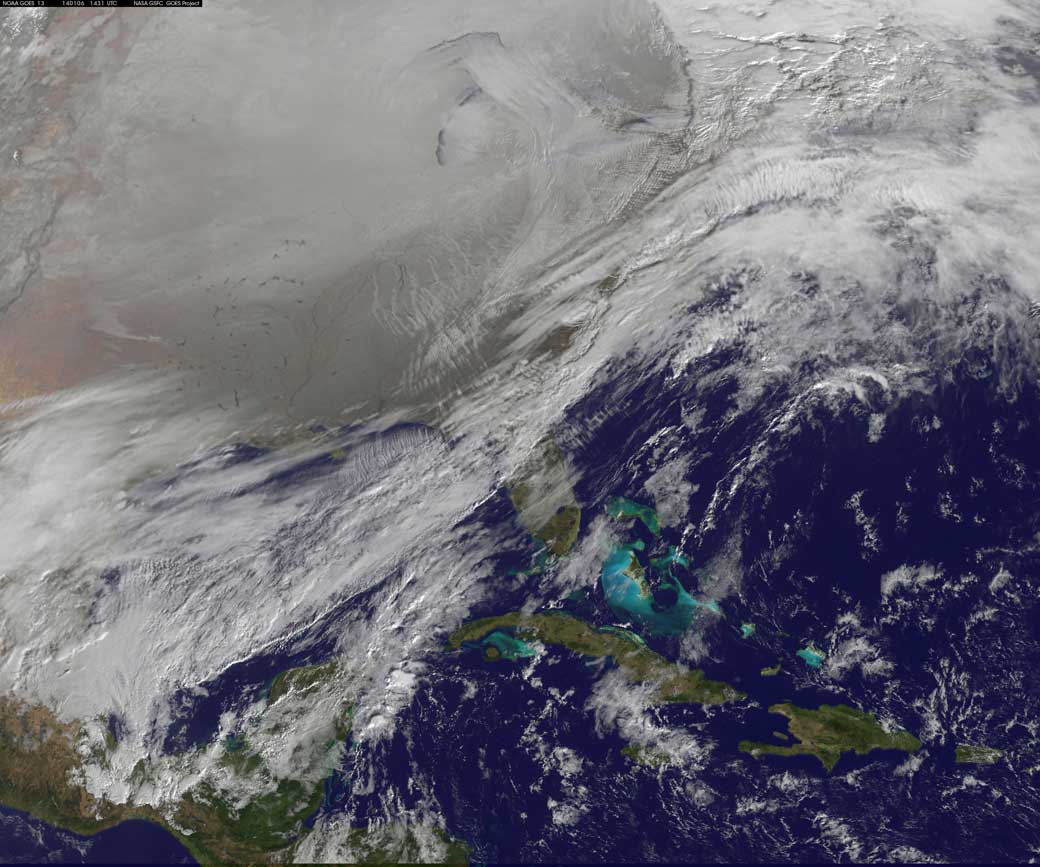

WASHINGTON – A new study says that as the world gets warmer, parts of North America, Europe and Asia could see more frequent and stronger visits of cold air.

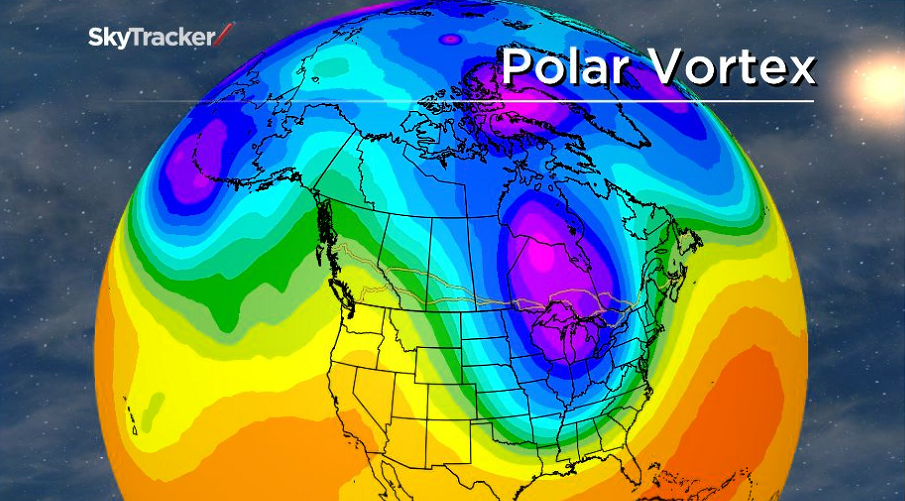

Researchers say that’s because of shrinking ice in the seas off Russia. Less ice would let more energy go from the ocean into the air, and that would weaken the atmospheric forces that usually keep cold air trapped in the Arctic.

READ MORE: Polar vortex lays waste to Ontario merlots, sauvignon blanc

But at times it escapes and wanders south, bringing with it a bit of Arctic super chill.

That can happen for several reasons, and the new study suggests that one of them occurs when ice in northern seas shrinks, leaving more water uncovered.

Normally, sea ice keeps heat energy from escaping the ocean and entering the atmosphere. When there’s less ice, more energy gets into the atmosphere and weakens the jet stream, the high-altitude river of air that usually keeps Arctic air from wandering south, said study co-author Jin-Ho Yoon of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington. So the cold air escapes instead.

Get breaking National news

That happened relatively infrequently in the 1990s, but since 2000 it has happened nearly every year, according to a study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. A team of scientists from South Korea and United States found that many such cold outbreaks happened a few months after unusually low sea ice levels in the Barents and Kara seas, off Russia.

The study observed historical data and then conducted computer simulations. Both approaches showed the same strong link between shrinking sea ice and cold outbreaks, according to lead author Baek-Min Kim, a research scientist at the Korea Polar Research Institute. A large portion of sea ice melting is driven by man-made climate change from the burning of fossil fuels, Kim wrote in an email.

Sea ice in the Arctic usually hits its low mark in September and that’s the crucial time point in terms of this study, said Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. Levels reached a record low in 2012 and are slightly up this year, but only temporarily, with minimum ice extent still about 40 per cent below 1970s levels, he said.

Yoon said that although his study focused on shrinking sea ice, something else was evidently responsible for last year’s chilly visit from the polar vortex.

In the past several years, many studies have looked at the accelerated warming in the Arctic and whether it is connected to extreme weather farther south, from heatwaves to Superstorm Sandy. This Arctic-extremes connection is “cutting edge” science that is hotly debated by mainstream climate scientists, Serreze said. Scientists are meeting this week in Seattle to look at the issue even more closely.

READ MORE: Polar vortex in summer? Not quite

Kevin Trenberth, climate analysis chief at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, is skeptical about such connections and said he doesn’t agree with Yoon’s study. His research points more to the Pacific than the Arctic for changes in the jet stream and polar vortex behaviour, and he said Yoon’s study puts too much stock in an unusual 2012.

But the study was praised by several other scientists who said it does more than show that sea ice melt affects worldwide weather, but demonstrates how it happens, with a specific mechanism.

Katharine Hayhoe, a Texas Tech climate scientist in Lubbock, said the study “provides important insight into the cascading nature of the effects human activities are having on the planet.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.