Watch above: Ticks that carry the debilitating Lyme disease have been found in Edmonton. Kendra Slugoski finds out how dangerous the threat is.

EDMONTON — With sunny weather and lush wilderness across Canada, many people are heading outdoors for camping, hiking or picnics in wooded areas. That’s also where a serious health risk could be lurking in the form of small, blood-sucking ticks.

These insects become infected once they’ve fed on mice, squirrels, birds or other small animals carrying the potent burgdorferi bacteria. The bacteria, which can cause Lyme disease, is present in about 20 per cent of black-legged ticks.

Of the 139 found in Alberta last year, one in five tested positive for the bacteria; and that number has health officials on alert.

“People are getting ticks anywhere — their backyards and the river valley. There doesn’t seem to be any pattern we can pick out,” said Daniel Fitzgerald, a laboratory technologist with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development.

Alberta Health says it’s not yet possible to know if ticks carrying the bacterium linked to Lyme disease are established in Alberta; but they are ramping up surveillance efforts. Under the “submit-a-tick” program, Albertans who find a tick on themselves or on a pet are asked to bring it to either a vet or an Alberta Health Services Environmental Health office.

Alison Glass was bit by a tick in Germany nearly seven years ago. At first she thought it was “a mosquito gone wrong.” A few months later, she says: “I felt like I was ready to die, any minute now.”

A large circular rash on her torso, was just one of the symptoms of Lyme disease she was exhibiting.

- Roll Up To Win? Tim Hortons says $55K boat win email was ‘human error’

- Bird flu risk to humans an ‘enormous concern,’ WHO says. Here’s what to know

- Halifax homeless encampment hits double capacity, officials mull next step

- Ontario premier calls cost of gas ‘absolutely disgusting,’ raises price-gouging concerns

Glass says getting treatment for the disease, which still affects her, hasn’t been easy. She hopes the province’s ramped up surveillance will also increase awareness about the condition.

READ MORE: Lyme disease still a controversial diagnosis, as Alberta cases climb

Lyme disease and ticks

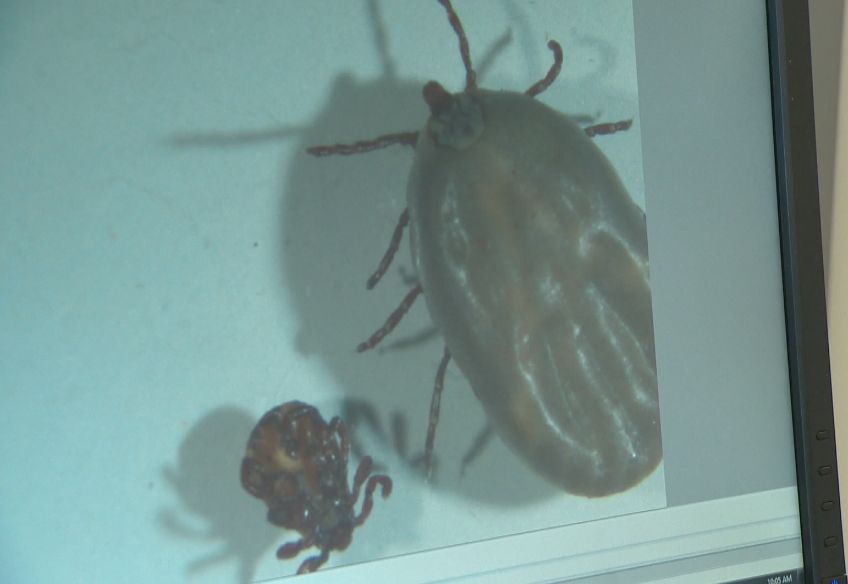

The ailment is named after Lyme, Conn., where the illness was first identified in 1975. It’s a bacteria transmitted through the bites of infected deer ticks, which can be about the size of a poppy seed. Female ticks can grow up to 100 times their original size after feeding on blood, according to Fitzgerald.

Unlike mosquitoes that can transfer West Nile to humans with a single bite, the tick has to be attached to the body for at least 24 to 36 hours. That’s enough time for the bacteria in the insect’s gut to make its way into replicating.

How to protect yourself against ticks:

- Wear light-coloured clothing. It makes ticks easier to see and remove before they can attach to feed.

- Wear long pants and a long sleeved shirt, closed footwear and tuck your pants into your socks.

- Use a tick repellent that has “DEET.” Apply it to your skin and outer clothing.

- Examine yourself thoroughly for ticks after a day out and use a mirror to check the back of your body.

How to safely remove a tick:

If you do find a tick, it’s important to remove it as soon as possible. If it’s removed soon enough, treatment may not even be necessary.

- Try not to squash it.

- Do not apply matches, cigarettes, or petroleum jellies to the tick as these may cause an infected tick to release the bacteria into the wound.

The video below demonstrates how to pull a tick out with a pair of tweezers:

Symptoms to watch out for:

If you have been infected by the potent bacteria ticks can carry, you could show the following symptoms within three to as long as thirty days:

- A rash at the site of the bite

- Headaches

- Fevers

- Muscle aches

- Chills

These symptoms appear to be the onset of Lyme disease.

If it’s left untreated, it could move onto the second stage of the disease. The tick’s victim is left with multiple skin rashes, arthritis, heart palpitations, and central and peripheral nervous system disorders.

A third and final stage is recurring arthritis and neurological problems, according to Health Canada.

You can find more information on the multitude of Lyme disease symptoms on the Canadian Lyme Disease Foundation website.

Diagnosis and treatment

Several antibiotics can treat Lyme disease but health officials emphasize the importance of earlier identification and treatment.

In some cases, Lyme disease can be cured within a two-to-four-week period.

Lyme disease on the rise in Canada: scientist

“People should be aware that this is really an emerging disease and they should take precautions to avoid being bitten,” Dr. Robbin Lindsay said last year.

Lindsay is a research scientist with the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory.

The ailment became a nationally reportable illness only in 2009.

According to Lindsay, an expanding population of ticks has been adding to the increasing number of Lyme disease cases in Canada. In 2011, for example, there were 258 human cases – a significant climb from previous years. Other organizations peg the number even higher.

“We’re definitely seeing a trend in the upward direction,” Lindsay said.

READ MORE: Climate change may be reason ticks are spreading across Canada

The experts suggest the uptake in ticks may be linked to rising temperatures. The bug-friendly climates are making it easier for the ticks to distribute into new areas.

More conditions linked to tick bites

The little insects may be the predominant culprit of Lyme disease but they’re also responsible for carrying at least three other disease-inducing agents.

“These ticks are not a one trick pony,” Lindsay warned. He said the tick bites could lead to other often overlooked conditions.

A prime example is anaplasma phagocytophilum, a flu-like illness that was first identified in the 1990s that’s even recognized in Europe now.

Another is babesiosis – caused by microscopic parasites that infect red blood cells spread by certain ticks. Lindsay calls it a “malaria-like” parasite and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that those who are infected often do not show symptoms.

In this case, the ticks carrying these parasites are in parts of the Northeast and upper Midwest of the United States, the CDC says.

Powassan encephalitis virus is named after the Ontario town it was first diagnosed in. It’s a rarity though – only a couple dozen cases have been documented since the 1950s.

Lindsay tells readers that conditions other than Lyme disease don’t conventionally occur after getting a tick bite. The incidence rate is about one per cent or less.

Information provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health

With files from Jennifer Tryon and Heather Yourex, Global News

Comments