Opinions on Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its, admitted or not, involvement in the Ukraine crisis vary in former Soviet states.

Ukraine is obviously unhappy about losing a chunk of its territory, while Kazakhstan has said it recognizes the results on Sunday’s referendum.

But, some countries with Russian populations are watching and wondering if Moscow may be knocking on their doors next.

Moldova’s Transnistria region

Take for example Moldova and its breakaway region of Transnistria.

The narrow strip of territory, sandwhiched between Moldova and western Ukraine, has been fighting to not be a part of from Moldova pretty much since the breakup of the Soviet Union.

BELOW: Map of Moldova and Transnistria

But, it’s not aiming to become its own country: the region wants to go back to Kremlin rule.

More than 30 per cent of Transnistria’s population identifies as ethnic Russian and the region relies heavily on Moscow for economic support.

Moldova’s overall Russian population, including the population of Transnistria, is about 5.8 per cent of its 3.58 million people.

In the wake of the Crimean referendum, the results of which have been widely dismissed by Western governments, Transnistria – also known in English as Trans-Dniester and Transdniestria – has reportedly asked Russia to consider allowing the region to join the Russian Federation.

Moldova’s reaction: Don’t even think about it, Russia.

“If Russia makes a move to satisfy such proposals, it will be making a mistake,” Reuters reported President Nicolae Timofti saying on Tuesday.

The bid to join Russia has been made before. A 2006 referendum ended with 97.2 per cent of voters choosing to join Russia.

Get daily National news

The region had essentially broken away from Moldova before the Soviet Union collapsed, then fought a four-month war for independence in 1992. The region declared independence at that time, but that was not recognized by any government – including Russia.

Transnistria’s government issues citizens its own passports and uses its own currency, the Transnistrian ruble.

Moldova, which is one of Europe’s poorest countries, has long been leaning toward closer relations with the European Union – which was a divisive issue in Ukraine, leading to months of protests, the eventual impeachment of pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych for his violent reaction to those protests and Crimea’s vote this week to breakaway and join Russia.

- 1 person shot, in critical condition in incident involving U.S. Border Patrol

- Vegas casino owner introduces ‘at par’ pricing for Canadian tourists amid slump

- Border Patrol commander Greg Bovino leaving Minnesota after 2nd fatal shooting

- U.S. sending ICE agents to Winter Olympics in Italy for ‘security’

Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia

Then there’s the three Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia – all of which are feeling a little bit leery after Russia’s intervention in the Ukrainian crisis and the annexation of Crimea.

The trio are the only former Soviet nations that have joined the European Union and NATO.

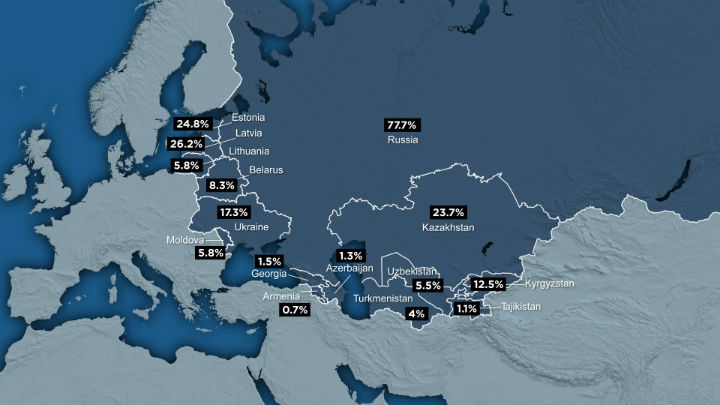

Both Latvia and Estonia still share longer borders with Russia, particularly the Pskov region, and have sizeable Russian communities: 24.8 percent of Estonia’s 1.3 million people are Russian, while 26.2 per cent of Latvia’s 2.1 million citizens are Russian.

Lithuania shares a small border with the Russian territory of Kaliningrad and has a much smaller Russian population, just 5.8 per cent.

Estonia has particular reason to be concerned about what’s happening in Ukraine.

In the wake of Yanukovych’s ousting, Russia vowed to protect Russian speakers in Crimea and Ukraine. While the Kremlin maintained it did not invade Crimea, Western eyes see the increased presence of Russian military uniform-wearing gunmen and its support for the referendum as an invasion into sovereign territory.

How does this relate to Estonia? Reuters reported last week a Russian envoy to the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva was quoted as saying Moscow is “concerned by steps taken” in Estonia to use language to “segregate and isolate groups,” referencing a similar situation in Ukraine.

BELOW: A map of Russian populations in the 15 former Soviet Union states

Despite living in Estonia, Russian-speakers must be able to speak Estonian in order to obtain citizenship and be able to vote in elections, Agence France-Press reported this week.

U.S. Vice President Joe Biden also pledged support for NATO allies such as Lithuania and Latvia on Wednesday, while visiting with their respective leaders in the Lithuanian capital Vilnius.

It may seem like speculation to consider that Russia may interfere with the Moldova-Transnistria situation or move to protect ethnic Russians or Russian speakers in the Baltics.

But it’s not so far-fetched in the eyes of NATO.

NATO chief Anders Fogh Rasmussen said, in an address to the Brookings Institution on Wednesday, Russia’s annexation of Crimea was part of a larger strategy and that is should serve as a “wake-up call,” The Associated Press reported.

“This is the gravest threat to European security and stability since the end of the Cold War,” Fogh Rasmussen said. “We need to take tough decisions in view of the long-term strategic impact of Russia’s aggression on our own security.”

With files from Dani-Elle Dube The Associated Press

*Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated 60 per cent of the population of Transnistria is speaks Russian. This has been corrected to read 30 per cent of the population identifies as ethnic Russian.

Comments