Scientists have discovered what are believed to be the oldest mummies in the world, created by smoke-drying some 12,000 years ago.

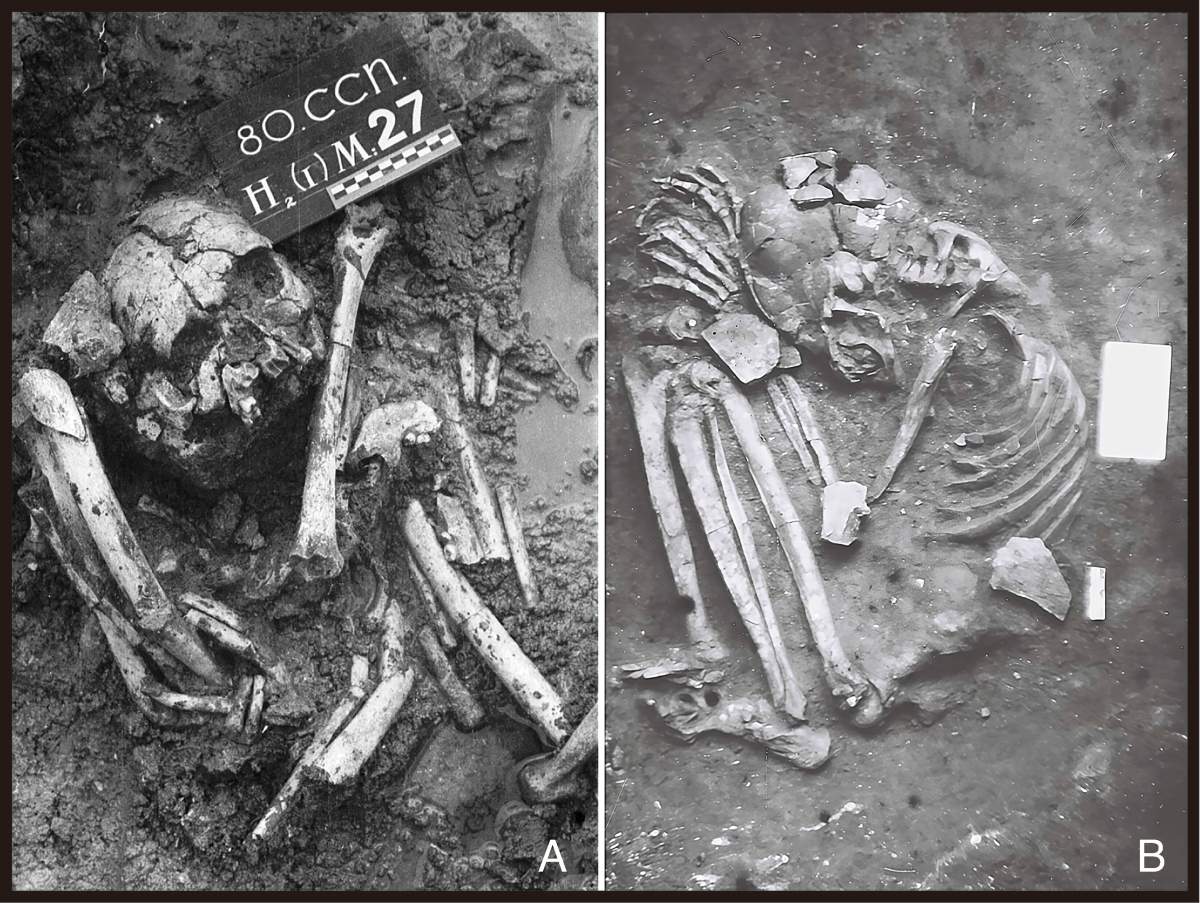

A study of ancient gravesites in China, the Philippines, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia revealed skeletal remains buried in a curled-up position that were smoke-dried over a fire for extended periods, as part of a mummification and burial process.

The research was published on Monday in the multidisciplinary scientific journal PNAS.

Mummification prevents the body from decaying and was a common technique used to preserve corpses in many cultures, most famously in ancient Egypt, where human remains were embalmed as part of mummification.

The researchers wrote that the mechanism used to smoke the bodies likely did not involve intentional direct burning, but rather caused blackening and discolouration of particular body parts rather than total combustion.

Until now, some of the oldest mummies known to man were prepared about 7,000 years ago in what is now modern-day Peru and Chile by a fishing people called the Chinchorro, according to PNAS.

Despite scientists’ recent findings moving the timeline back, human evolution expert Rita Peyroteo Stjerna at Uppsala University in Sweden, who did not participate in the research, told ABC News that it is not yet clear if all mummies in the region were smoke-dried.

Meanwhile, the lead author of the study noted that the discovery offers significant insight into the behaviours and belief systems of ancient communities from the area.

Further studies of the remains revealed that many of the bodies were buried similarly, typically in a squatting position, and were likely interred by hunter-gatherer communities, offering an “important contribution to the study of prehistoric funerary practices,” Stjerna told the news outlet in an email.

Get daily National news

According to the study, the burial samples highlight a “remarkably enduring set of cultural beliefs and mortuary practices that persisted for over 10,000 years among hunter-gatherer communities,” and in some instances indicate dismemberment post-mortem.

Smoke-drying mummies is still being practised today in parts of Southeast Asia, the researchers wrote, who conducted research in Papua, Indonesia, in January 2019, where they studied the Dani and Pumo people creating mummies in this manner.

The study says researchers observed them tightly binding corpses, compressing their four limbs to the body, holding them over a fire, and smoking them until they turned entirely black.

Among the Dani, the descendants of the deceased keep the mummy in a designated room within the house and bring it out on special occasions.

“These highly compact examples are very similar to those from our study sites in Southeast Asia,” the study says.

Researchers consider the remains they discovered to be mummies because they were deliberately mummified through smoke-drying, even though their flesh, hair and skin were not preserved.

“The key difference from the mummies we typically imagine is that these ancient smoked bodies were not sealed in containers after the process, and therefore, their preservation generally lasted only a few decades to a few hundred years,” Hung said.

In the hot and humid climate of Southeast Asia, smoking was likely the most effective way of preserving the bodies, she said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.