TORONTO – When people talk about reducing their carbon footprint, they may think of doing that by using solar panels or wind turbines. However, there’s another way that not only individuals, but entire cities can reduce their carbon footprint: district energy.

Guelph, Ont. is aiming to become the first city in North America to do that with a city-wide district energy network.

District energy is a network of systems used to heat or cool a several buildings. It can be traced back to the early Romans, with aqueducts and a process called evaporative cooling where fountains of water would be cooled by air and would in turn cool buildings.

The first district energy system in Canada was introduced in the early 1880s in London, Ont. It provided heat for university, hospital and government buildings. The first commercial district energy system in Canada was in 1924 in Winnipeg.

“It’s not a new technology, but there are so many improvements in the actual technology that are used…that make it much more economically viable now than ever before,” Jean Duquette, a researcher at the University of Victoria’s Institute for Integrated Energy Systems told Global News.

“It’s a huge, huge capital investment that usually stops these projects in their tracks,” said Duquette.

But Guelph is taking the challenge head on.

“It has some very fundamental bottom line goals around energy-use per capita, 50 per cent less,” Rob Kerr, Guelph’s Corporate Manager of Community Energy told Global News. “And greenhouse gases per capita, 60 per cent less, both by 2031.”

Get daily National news

Kerr said that the city is financing the system and residents won’t see taxes increased due to the project.

That’s quite a challenge: The city projects large growth — by more than a third — within that time frame.

“It’s very ambitious,” Kerr said.

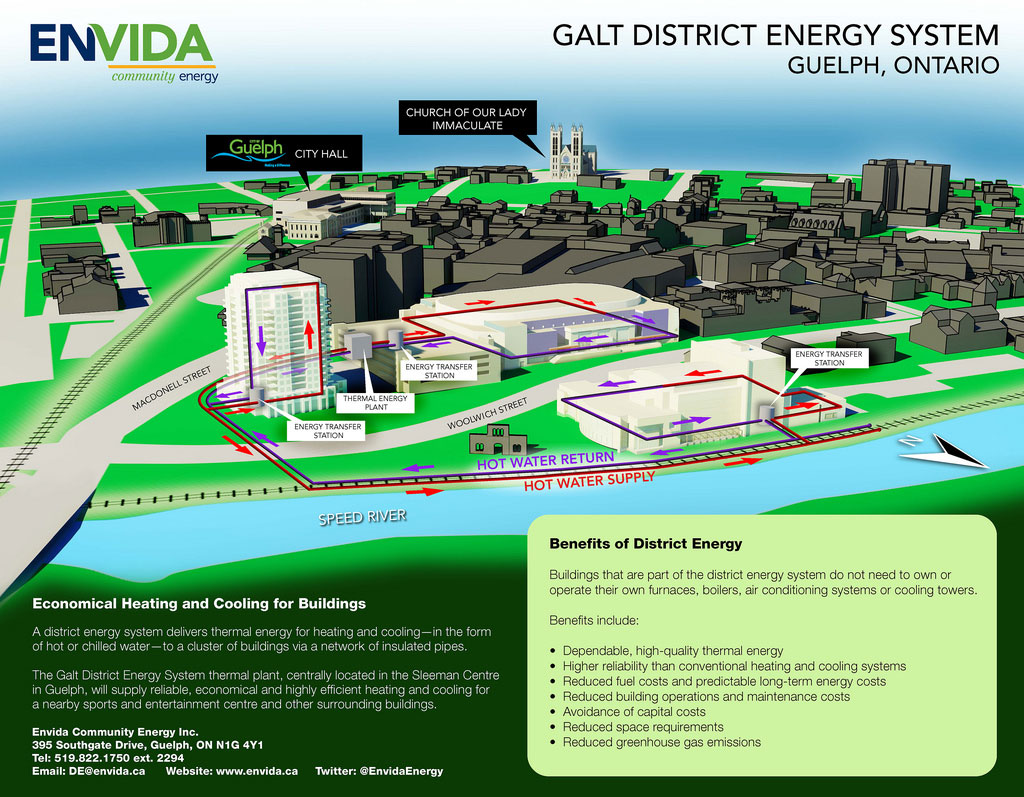

The first building, or node as it’s called in the system, is the Sleeman Centre, the city’s large sports and recreational centre. It has already started contributing to the system.

“It’s a natural first customer,” Kerr said. “The Sleeman Centre is not only the first customer but is also the host to the heating plant that will create heat for the entire neighbourhood.”

The city is moving out from that building to serve the River Run Centre, a theatre across from Sleeman and is in negotiations with a list of private sector buildings.

District heating is used across Europe in cities in Germany, Denmark and England. Because heating or cooling a home or building comes from a central location, it’s extremely efficient.

“Instead of having every individual home…who all have their own separate systems, every system has its own efficiency,” Duquette said. “So if you have a boiler, or a furnace to heat your house, it works very well.”

This, Duquette said, is because using our current method of heating — with furnaces or boilers, for example — would work at just half its capacity during the coldest time of the year.

“What’s nice about a district energy system is that everyone is using the same furnace or same boiler, so all of these peaks…it basically levels off overall. So you have one system that’s running at optimal efficiency providing energy to everybody.”

Another advantage to district energy systems, aside from their ability to reduce a city’s carbon footprint is the flexibility of fuel: a multitude of sources can be used throughout the system, something that Guelph seeks to capitalize on. Currently the city has 200 homes or buildings with solar panels. The city could use that as part of the integrated system. Some other sources are geothermal, natural gas, or biomass.

Making the city denser is also key to improving its efficiency.

“Integrated is the keyword,” said Kerr. “We are trying to create a platform in our community to attract investment, to stimulate activity,” he said.

Though Guelph seeks to be the first city to use an entire network, there are other cities throughout Canada that use some form of district energy.

In Toronto, Lake Ontario provides heating and cooling to some buildings in the downtown core. North of the city, in Markham, a district energy system is used to heat and cool buildings like the city hall and several residential and commercial buildings.

According to the Canadian URBAN institute and the Canadian District Energy Association, almost 120 district energy systems were operating in Canada in 2009 across nearly every province. Of that, Ontario has the highest number with about 43 per cent.

But district energy still represents only about 0.29 per cent of total sales of energy in Canada.

With newer technology and more cities seeking to save money and reduce their carbon footprint, there may be more cities like Guelph in the years to come.

Comments