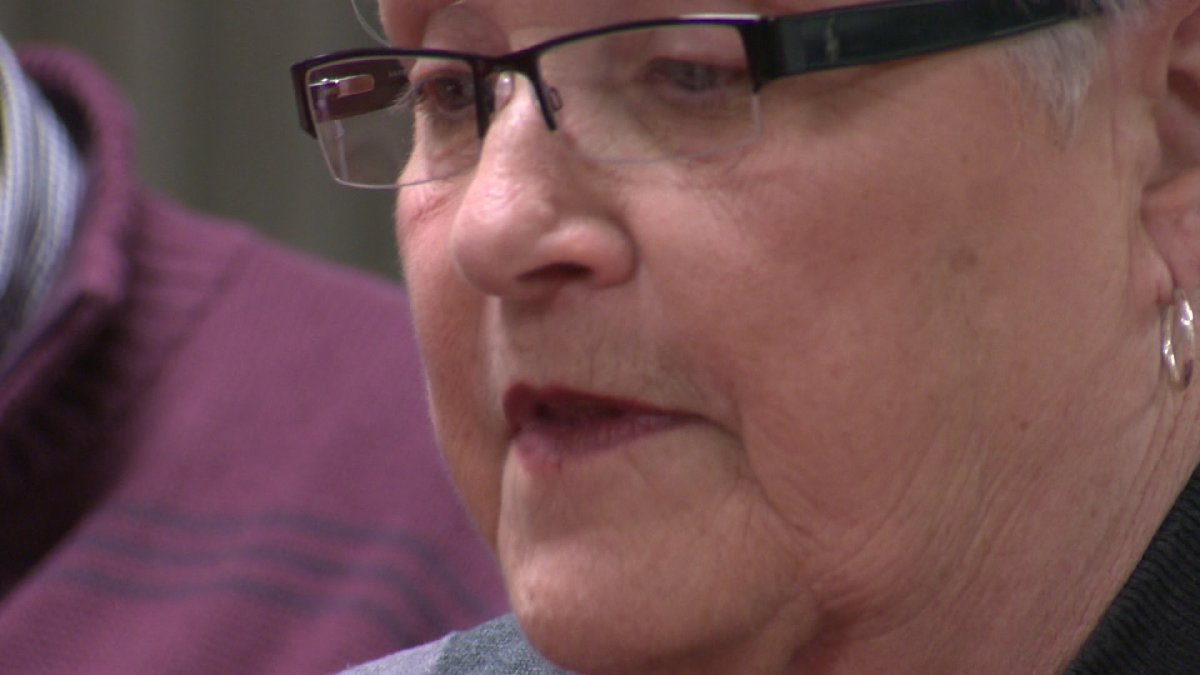

HALIFAX – Speaking has been a struggle for Ginny Doucet ever since her stroke seven years ago, which then lead to aphasia.

“I still…lots of things I can’t talk,” she said, speaking slowly. “It’s in your head but it won’t come out.”

Doucet spent three weeks in hospital after her stroke, then three months at the Nova Scotia Rehab Centre.

“I couldn’t talk,” she said. “Nothing at first but with some help, I got better.”

Aphasia, a language communication disorder, affects an individual’s ability to read, speak, write and comprehend.

It is often caused by strokes but is also triggered by head injuries, brain tumours and other neurological conditions.

The senior worked in a bank for 30 years but her aphasia has now made it difficult for her to count money. She continues to work with a speech therapist.

Doucet’s speech has been improving, however, thanks in part to a monthly meeting in Halifax for people like her who live with aphasia.

The Expressive Cafe, run by the Nova Scotia Aphasia Association, gives aphasia patients and their loved ones a safe space to communicate and a community to lean back on.

“You’re with people that have the same things with you, on you, you know what I mean.” Doucet says the group is a comfort at a time when the simple act of piecing a sentence together can be a nerve-wracking, Herculean effort.

Get weekly health news

“It makes me worse when you think it’s in your head, when you get to try it out, it doesn’t come out right,” said Doucet.

“It doesn’t come out right. Then you get more nervous and that makes it worse you know.”

Gord McNeil had a stroke in September 2012 and has been dealing with aphasia ever since.

“I couldn’t say any words so I had to learn the sounds to make the words and then I had to develop my speech,” he said.

McNeil says life with aphasia is difficult but notes that he’s happy he retained his ability to speak at all.

“It’s slow going,” he said of his progress. “But it’s worth it.”

The senior reflects on an incident where he wanted to respond to an email with “Ok” but found himself struggling due to his disorder.

“I got the “o” and I couldn’t figure out for the life of me what came next. I tried all the letters of the alphabet and nothing, nothing seemed to work,” he said.

But with the monthly meeting, McNeil finds that he is not alone.

Judy Arbique, president of the Nova Scotia Aphasia Association, said 500 people in the province develop the condition every year.

Arbique, who also has aphasia, said group members tell stories to practice their speaking skills and sometimes play games like bingo, charades or Pictionary.

The whole point of the cafe, she said, is to get people out and interacting with one another.

“To have loss of your communication skills, it’s a loss of confidence and self esteem,” she said.

But, she said group members create an environment of understanding, support and, most importantly, encouragement.

“Each person in the group has different challenges, learning about own conditions and to understand and then explore resources in using them to get better language skills.”

Doucet can attest to that; she is hopeful for a full recovery.

“I would hope to but I’m not sure. We’ll just have to do it one day at a time,” she said.

Her fellow group member McNeil is confident though that his condition will improve.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever get to where I was, but I can still get better.”

The Aphasia Institute estimates there are more than 100,000 Canadians living with aphasia.

Comments