As rents continued to surge across Ontario during the past year, availability for people trying to make a home in a given city got a lot tighter, according to Canada’s housing agency.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.’s (CMHC) latest annual rental market report, which surveys property managers on key statistics like costs and turnover, continues to paint a picture of low vacancies and rents growing much faster than people’s incomes.

Pauline Roberts, who moved to Hamilton from Winnipeg some 20 years ago, remembers how easy it was to find a spot for just $800 a month when she took on a role as a personal support worker in Oakville.

“No problems,” she recalls. “There was no problem finding a place.”

However, the mother of three had to leave Ontario in 2016 and move to Calgary to care for her father suffering from cancer.

“So when I officially came back to Hamilton in 2019 after my father passed away, It was ridiculous,” Roberts says. “A one-bedroom was $1,600 to $2,100. I’m like … yeah … there’s no way.”

Roberts has lived in five different locations across the city since then, was homeless for eight months, and is now in a space that she claims has been deemed an illegal dwelling by the city.

The 49-year-old is one of 6,000-plus people on the city’s affordable housing waitlist and is fearful she may be thrown out of her current Gage Park area rental.

“If bylaw comes and evicts, I’m looking at being on the street again. So I live in fear every day,” Roberts says.

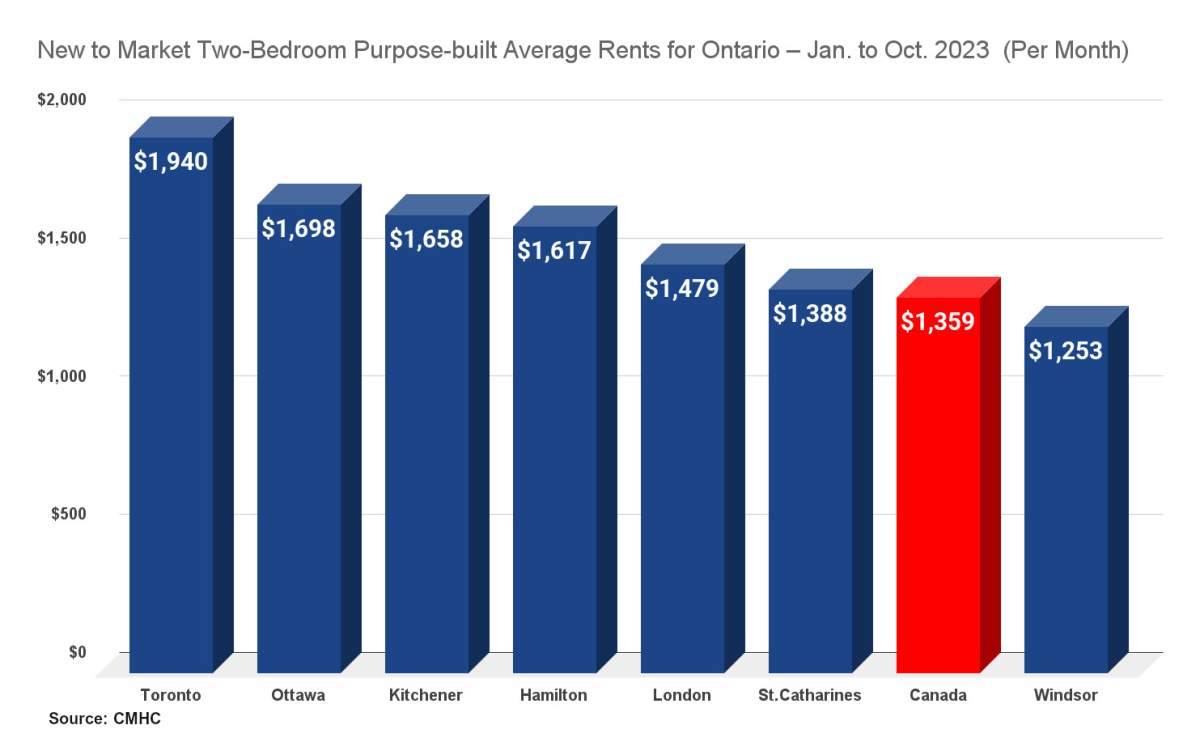

The rental market in Hamilton is as tough as it gets in Ontario with costs up 13.7 per cent year over year for an average two-bedroom purpose-built unit between January and the end of September.

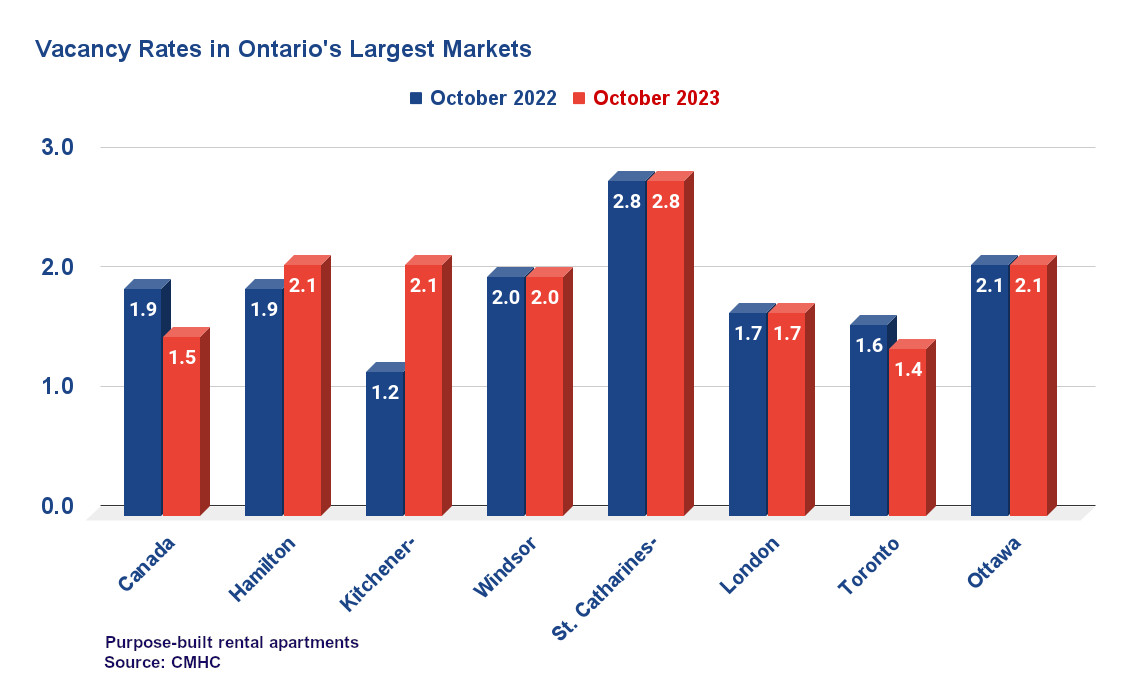

Those units, priced at an average of around $1,617 a month, accounted for a record-low vacancy rate of around 2.1 per cent across the city.

Get breaking National news

Finding a condominium-style dwelling was a bit easier, with a vacancy rate of 2.6 per cent, but at an average price of $2,373.

Hamilton’s rent increase represented the second highest of 18 cities surveyed in Canada, just behind Calgary’s 14.3 per cent jump.

Those most affected by high rents were renters new to the market, especially young workers earning minimum wage.

CHMC’s senior analyst for southern Ontario Anthony Passarelli says record international migration and a booming young adult population is a big part of a trend creating “robust rental demand” while stifling homeownership opportunities.

“It started to happen in the last few years because of that crunch on the homeownership market where people can’t move out of a rental to buy,” Passarelli said. “And the population growth just being so strong and supply not keeping up.”

- Stepfather of two missing N.S. kids charged with sexual assault of adult, forcible confinement

- 10 people abducted from Mexico mining site, confirms Vancouver-based firm

- Canadians have billions in uncashed cheques, rebates. Are you one of them?

- Is Canada making progress in knocking down internal trade barriers?

International migration, up a record 56 per cent in Ontario as of July 1, played a part in putting non-permanent residents with work and study permits into the mix. Some 280,000 study permits for international students were handed out across Ontario, up 30 per cent compared to January and September of 2022.

The millennial cohort in Hamilton, people born from the early 1980s to the early 2000s, was up five per cent in 2023. That group now represents about 40 per cent of all households seeking a rental in the city, according to census numbers.

Pasarelli says that led to the double-digit growth in two-bedroom rents and a resulting lack of available units.

“So when a unit came back on the market, there was intense competition for those units, which really drove up the rents overall in the region,” he revealed. “Because … most of them are rent-controlled, it would have been only a 2.5 per cent increase (in rent) if you didn’t move.”

Finding a rental in the Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo region became easier year over year as the vacancy rate rose to 2.1 per cent in 2023 compared to the 1.2 per cent seen the previous year.

The CMHC report attributed that bump to “significant additions” in new rental supply across the region.

However, rising interest rates and high house prices putting a lot of potential homeowners on the sidelines and kept the regions vacancy numbers in line with other Ontario cities.

The report estimates a low-income earner under $49,000 a year in Kitchener-Waterloo seeking a two-bedroom dwelling had to dole out close to $380 more a month than they could afford, assuming affordable rent for a household is less than 30 per cent of their before-tax income.

Despite a nine per cent increase in supply year over year, renters in Toronto looking for a two-bedroom condo-style apartment battled a low 0.7 per cent vacancy rate in 2023.

On top of that, a two-bedroom rental sets an average household back about $2,862 a month.

Passarelli says not a lot of relief is coming for renters in the short-term, but says recent “banging of the drum” appears to be delivering the message to the three levels of government about the country’s housing needs.

“It really drives home how bad the situation has gotten and how much more supply is needed to be added,” he says. “Seems like all the levels of government are finally on the same page, and really pushing forward this agenda of increasing the supply as quickly as possible.”

Roberts, who joined the advocacy group ACORN in 2022, is putting her hope for stable housing behind the recent passing of renoviction bylaws that aim to stifle attempts by landlords to end tenancy via repair applications.

“That is something that Hamiltonians should be proud of, because we are the first city in Canada that had two bylaws passed in one day,” said Roberts.

Comments