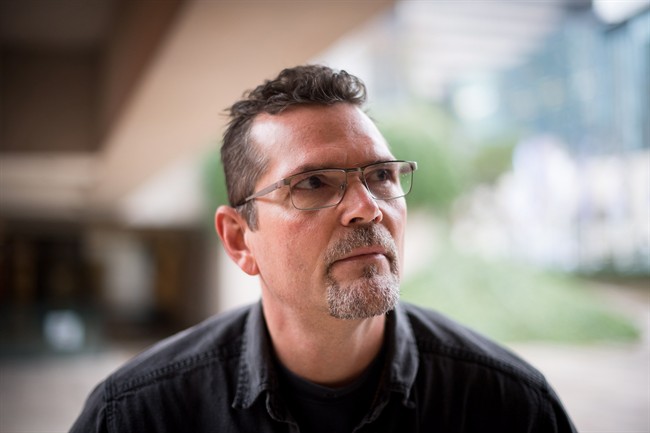

VANCOUVER – John Lenec remembers the song “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” going through his head moments after he slipped off a detox centre bed and began convulsing on the floor. It had been six hours since his last hit of heroin.

“It was a scary moment for me,” Lenec said of his withdrawal experience in early 2007. “I’ve never felt like that in my life.”

This year’s surge in fentanyl-related deaths has highlighted the struggle of people suffering from drug addiction, raising questions around the origins of substance dependency and the challenges associated with overcoming it.

People who use opioids such as fentanyl talk about the pain of withdrawal, and some say the main reason they continue to use drugs is to avoid the experience.

WATCH: Overdose deaths reach shocking new levels

Lenec’s detox stint in New Westminster, B.C., in 2007 was just one of his dozens of unsuccessful attempts to overcome a drug addiction he had struggled with for more than three decades.

At his peak, Lenec was using a quarter gram of heroin every four hours, or 1 1/2 grams daily — so much that even his dealer advised him to slow down.

“Withdrawal starts with the panic in your head that you’re running out of drugs,” Lenec said.

“Then once you’ve had some abstinence for two, five, six hours, depending on your length of use and amount of use, you start feeling a little nauseous. Lower-back pain kicks in. You start getting sweats. Then chills will run up your body.”

Fentanyl overdoses killed hundreds of Canadians this year, experts say 2017 could be deadlier

He would go from sweating to hiding under the covers trying to stay warm before the nausea would kicks in, Lenec said.

“You start vomiting. Then once everything is out of you, you still vomit. You’re dry-heaving. You’re going so hard that your stomach hurts. Your muscles are going. You have major diarrhea for one, two days. Then you’re blocked.”

WATCH: B.C. nurses and firefighters say overdose crisis is taking toll

And the hardest part is knowing that “all this could go away with one puff,” he said.

Lenec hasn’t used drugs illicitly for nearly four years.

Hugh Lampkin, a longtime drug user and community advocate in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, said he would never again go through the horrors of withdrawal.

9 overdose deaths in one night prompt officials in Vancouver to demand more treatment

“If anybody who has never done drugs had one hour of dope sickness, I guarantee you they’d never want that feeling ever again in their entire life. Ever,” Lampkin said, explaining how quickly an opioid addiction can develop.

- ‘It’s nice to be the villain’: Vancouver Canucks gear up for Game 3 in Nashville

- ‘Why aren’t we doing more?’ White Rock on edge with killer on the loose

- Joffre Lakes to close for 3 periods this year under agreement with First Nations

- B.C. carjacking victim says she doesn’t trust the ‘catch-and-release’ system

“Before (you) realize it, you’re wired,” he said. “Before long you’re not doing it to get high. You’re doing it to not get sick, so you can feel normal.”

Research indicates opioids stimulate the brain’s reward system. But continuous use leads to tolerance and eventually dependence on the drug, to the point where the brain needs it to function normally, something users call “maintaining.”

Dr. Philip Berger, an addictions specialist and medical professor at the University of Toronto, said one of the primary motivators for people to continue using drugs is to relieve or avoid withdrawal.

B.C. paramedics to use bikes, ATVs to fight opioid crisis

He described the experience as similar to “a terrible flu,” but said symptoms typically subside after three to four days, more quickly than first-hand reports from some drug users.

Dr. Christian Schutz, a psychiatrist at the University of British Columbia, said opioids induce powerful chemical changes within the body, which he said means a drug user’s personal experience of withdrawal can vary.

“That’s another reason why people die,” Schutz said. “When they start using drugs they develop tolerance, so they need more of the substance to have the same effect.”

So if someone with a history of drug use abstains for a period, their tolerance wanes and there’s a risk of overdose if they return to using the same amount, he said.

Bill Wong has been clean from heroin and alcohol for 32 years, but he still remembers going through withdrawal.

“It’s a point of total, extreme pain — not only physically but mentally also. And this pain is unbearable,” he said.

“And then there’s the total obsession,” he added. “All you can think about is getting those drugs.

“It’s not a pleasant place to be.”

Comments