Ameeta Singh’s patients should know better.

The Edmonton doctor and infectious disease specialist is seeing more people with more severe sexually transmitted infections — young men with chlamydia and hemorrhagic proctitis who say they’ve had 30-odd partners in the past six months and didn’t use condoms half the time; seemingly healthy people who’ve been on intensive HIV treatment for ages and have contracted syphilis, gonorrhea, hepatitis C from unprotected sex.

“It’s frustrating,” she said.

“I don’t know what to say any more. I don’t believe that me saying anything is going to change their behaviour.”

READ MORE: Tracking sexually transmitted infections in a Tinder age

We’re better at treating, preventing and screening for sexually transmitted infections than ever before. But Canadian communities are seeing historic levels of syphilis and gonorrhea.

Ontario’s had sky-high syphilis rates for so long, it’s what University of Toronto epidemiologist Dionne Gesink calls a “mature epidemic.” Gonorrhea is catching up and is increasingly resistant to the only drugs we have to treat it.

“It’s about time this thing ends,” Gesink said.

“We don’t really know what’s driving this epidemic and keeping it sustained, because a lot of the traditional things we would do to end an epidemic aren’t working.”

Last month Alberta declared a public outbreak for both syphilis and gonorrhea. The province’s infectious syphilis rates more than doubled between 2014 and 2015 after several years of slow growth — even as Canada faces a national shortage in the drugs used to treat the disease.

In Alberta, as in Ontario, the jump in STIs was overwhelmingly among men.

Note: Our data is gender-binary. It’s less than ideal but it’s all we’ve got right now. We think it’s worth using.

Gonorrhea has also increased, albeit not as steeply and with less of a gender disparity.

And there’s a significant disparity between health regions.

Edmonton has seen by far the biggest increase and highest rates, almost doubling Calgary, which is second-highest.

- As Canada’s tax deadline nears, what happens if you don’t file your return?

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Drumheller hoping to break record for ‘largest gathering of people dressed as dinosaurs’

The infectious syphilis rate among men in Edmonton rose the most dramatically — it more than quadrupled in a single year:

“The biggest rise in infectious syphilis cases has been among men who have sex with men, although we are seeing cases in heterosexual persons, as well,” Singh said.

“There’ve been a number of reasons put forward to try and explain that rise.”

READ MORE: Don’t blame hookup apps for casual sex; they just make it tougher to track

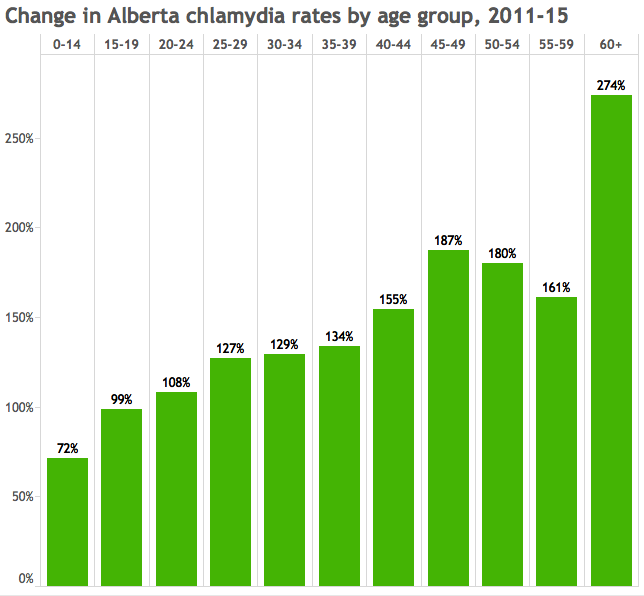

Steepest disease increase among people over 40

Alberta’s also seeing a spike in STI rates among people 40 years old and up — what Singh calls their “second peak” in sexual activity.

Between 2011 and 2015, syphilis rates among people aged 40 to 44 increased more than 2,000 per cent.

The second-steepest increase was among people 60 and over.

Chlamydia rates haven’t increased nearly as much, but they increased the most among people 60 and over:

“There’s a second peak in sexual activity” for people over 40, Singh said.

And in this respect, age does not bring wisdom or risk aversion (or an affinity for condom use).

“It does seem like the older people, I guess, either are not aware that they, too, are at risk of acquiring STIs, they haven’t thought about it, haven’t had to think about it for a long time, may presume their partner or partners are low risk.”

READ MORE: Safe sex misconceptions

Risk and reward

Singh also suspects people are having unprotected sex because they’re less afraid of contracting HIV, which has become much easier to treat and, with the advent of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), easier to prevent.

“I think that has increased risky sexual behaviour because they’re less concerned about getting HIV,” she said.

About a quarter of the infectious syphilis cases in Alberta are among people who are HIV-positive, Singh said. In Ontario,

“It definitely seems like the fear around HIV is just gone,” Singh said.

Or, as Gesink sees it, fear around HIV “dwarfs the other STIs. And you can only stress about so many things before you reach stress fatigue.”

Julio Montaner, who made a name for himself internationally through his work in HIV/AIDS treatment as prevention, does not buy the hypothesis that advances in tackling HIV/AIDS have made people have riskier sex.

“It has been long part of the folklore that if and when a treatment became available for HIV, or a prevention became available, that it could lead to behavioural dis-inhibition,” he said.

“The truth is that whenever this issue has been monitored carefully there is no evidence that people change their behaviour as a result of accessing treatment or even pre-exposure prophylaxis.”

We’ve got the causation backwards, Montaner says: If we’re seeing high STI rates among people who are on PrEP, Montaner said, that’s because PrEP is given to people with epidemiologically riskier sex lives.

“There’s a bit of a circular argument.”

There have always been risks associated with sex and that’s never stopped people from having sex, Montaner said: Lack of contraception doesn’t make people celibate, it just makes it more likely they’ll have an unplanned pregnancy. And while the spectre of a generation decimated by AIDS horrified people three decades ago, people didn’t stop having sex because there wasn’t yet an effective HIV treatment.

“There is a spectrum: There are people that are much more reserved in their sexual practices and there are others that are not,” Montaner said.

“Syphilis is currently out of control. It’s an epidemic that continues to rise. We’re all concerned about it, but we can’t blame antiretroviral therapy.”

As a consultant and research in gay men’s health with the Health Initiative for Men, Jody Jollimore’s job is helping people work though that risk-reward calculus.

“There are people who feel that getting a bacterial STI (syphilis or gonnorehea) is a negligible risk, worth having condomless sex. After all, they are treated with antibiotics like any other infection. It is possible to pick up bacteria from travelling or eating certain foods, but that doesn’t stop most of us,” he wrote in an email.

“The public health message: get tested more often. Make people feel comfortable enough to talk about their sex to their healthcare provider.”

Shame and stigma, he noted, “stop people from getting tested.”

‘We need a new approach’

The problem is the same as it’s always been, Montaner said: People like having sex. Many would rather have sex without condoms. Health advances have come up with ways of mitigating the risk of pregnancy and HIV transmission; we’re now up against a host of other diseases.

“The war on STIs has failed as we know it. We need a new approach,” he said.

Montaner’s already started looking: He and researchers from the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS have a $5 million provincial grant to research harm reduction when it comes to hepatitis C transmission — to treat people and lower the likelihood they’re infected again.

“How afraid do you have to be to not jaywalk? … It just doesn’t work that way,” he said.

“Education is the better way to go and help people to make better choices, support them in making better choices. And for those that cannot, will not and are not interested, we need to have a more effective compassionate approach.”

Comments