Maybe you heard: Canada’s books took a turn for the ugly over the past few months.

Or, as Finance Minister Bill Morneau put it when he unveiled his government’s fall economic update Friday morning, the economy “tilted to the downside.”

The federal budget is $6 billion poorer than last spring’s budget thought it would be after GDP growth fell in the first half of this year.

“This is the situation we’ve inherited,” Morneau said, calling these figures a “starting point” for his government to determine how the gloomy economic outlook will fit with his party’s pricey pledges.

“We will continue to be prudent with our decisions and we will make another budget with our promises,” he said.

“We built our platform with an understanding that we were facing a low-growth economy. So our decision to make significant investments in infrastructure were designed to both improve Canadians’ lives and provide some fiscal stimulus.”

What’s dragging Canada’s economy down?

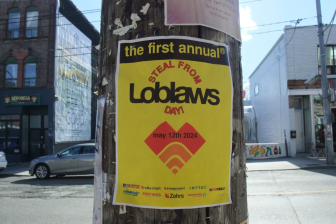

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

Blame commodity prices.

More specifically, blame oil.

The price of crude continues to tank, hitting its lowest point since 2009 last month at $46.22 USD a barrel:

Canadian oil inventories, meanwhile, hit their highest point in a decade in August (they dropped slightly in September). That’s a bad sign because it means companies that have ramped up oil production now can’t sell the bitumen they pulled out of the ground.

And that’s hit Alberta hard.

The province’s unemployment rate increased significantly overall, but it doubled between October 2014 and October 2015 for men, to its highest point since 2009:

And Alberta’s EI beneficiaries have more than doubled since August 2014:

But none of this should come come as a shock to anyone, says Mowat Centre chief economist and Ivey School of Business economist Mike Moffatt.

“Nobody should be surprised,” he said.

“I don’t think there’s any big bombshells here. It’s what we all suspected.”

These numbers are pretty close to ones the Parliamentary Budget Officer released earlier this month.

But they’re significantly less optimistic than Bank of Canada estimates the Liberals used in their election platform.

“When you design a platform, normally you would use publicly available numbers. So they used the most up-to-date ones that were available at the time, and those were from the Bank of Canada,” he said.

“That said, I think they would have at least entertained the possibility that the situation was worse than even the Bank of Canada was saying.”

So the Liberals are left with a choice they should have seen coming: Raise taxes, cut spending or run bigger deficits than the $10 billion a year they promised.

“Something has to give. No question,” Moffatt said.

“They’re going to get accused of breaking a campaign promise no matter what they do.”

Of the three, Moffatt figures the latter makes the most economic sense.

But it also may be the most politically palatable. Voters knew the Liberals were going to run deficits. Most people have a poor grasp of how much a billion is.

“I think the general public tends to see this as either, ‘You’re running a deficit or you’re not.'”

It’s also possible to run deficits of more than $10 billion a year and still reduce Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio, as long as the economy keeps growing.

(The slower the economy grows the less wiggle room the feds will have to run higher deficits. But Moffatt figures as long as annual economic growth doesn’t dip below 1 per cent and the deficit doesn’t get higher than $20 billion, they should be able to keep shrinking the debt-to-GDP ratio — or at least keep it from growing.)

And the only two spending cuts big enough to make a dent in Liberals’ budget — infrastructure cash and the new Canada Child Benefit — are there to provide economic stimulus and address inequity, respectively, and will arguably be more needed than ever during a slowdown, Moffatt said.

“Part of the rationale behind the Liberal platform to begin with is that the infrastructure spending would act as stimulus,” he said.

“It would be strange if the government pulled back on their stimulus in reaction to the news that the economy is even worse: It’d kind of be working at cross-purposes.”

INTERACTIVE: Click the options on the right to explore unemployment rates by province, gender and age

Comments