Julie Linkunatis loves to work.

“The more busy I was, the more happy I was. Not being busy makes me stagnant,” she said in an interview at her Brampton apartment.

Time was, she was working three jobs at once through different temp agencies, sleeping in her car between shifts. It was exhausting but brought in the cash she needed to support her youngest daughter Victoria and the mortgages she was left with after a breakup.

Linkunatis has worked as a forklift operator, an electrician, a baker; she’s lugged 200-pound mats, dismantled bleachers, delivered pizzas, built seats for Chrysler cars. One bitterly cold day she was that person who stands by the road wielding an oversized “Closing Sale” sign.

She knows how to hustle, calling one agency in the early hours of the morning when another job falls through.

As recently as seven or so years ago, “it was great,” she said. “I felt like they were really looking after us.”

The temp agencies are still there, she says – more of them than ever.

But the jobs are not.

“I’m finding dead ends. And it’s tragic.”

She’ll spend hours filling out paperwork for one agency after another and never get a call.

Employers have an advantage in the supply and demand equation, and she knows it.

“They can pick and choose who they want. … And I’m 54 years old. So that’s a barrier,” she said.

“There are a million people behind me who want that job.”

She figures she’s worked at least 10 jobs where she spent nine months at a company only to be fired just when she thought she’d finally get a full-time gig.

“It’s like a slap in the face.”

Read the series

- Canadians want to work. Why have so many stopped looking?

- Instability trap: When you’re income rich, but asset-poor

- Chequed out: Inside the payday loan cycle

- Feb. 23: Retirement lost

- Your Stories

Government response: What the feds had to say about Canadians’ labour instability trap

Sandwiched between work, family and bills to pay

Mary McPhee’s day begins pre-dawn.

By 5:30 a.m. she’s up and heading to her daughter’s house to give her a ride to work. Then it’s back to get her three grandchildren – aged nine, six and four – ready for school and drop them off.

Then McPhee, who’s employed through an agency as a personal support worker, will be with a client until about 2:30 p.m. – unless her parents need her, in which case that day’s work could be scuppered and, with it, her pay.

She picks up the three kids by 3 p.m. and stays with them until it’s time to pick up their mom from work; then she’ll work evenings and get home around 10 p.m.

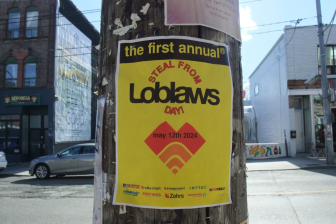

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- As Canada’s tax deadline nears, what happens if you don’t file your return?

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

Ask how she’s doing and the answer, on any given day, is “Crazy.”

McPhee has worked with agencies on and off for decades. She’d work independently but can’t afford to buy her own insurance, she says.

Sometimes agency work isn’t so bad: It can give her the flexibility she needs to care for multiple generations of her tightly knit family.

Other times it means less stability, less predictability, less cash – the agency takes a portion of what she makes caring from a client. Money for your uniform, and any criminal records check required, often comes out of whatever’s left, Linkunatis notes.

“You are at their mercy for some work,” Mcphee said. “It sucks when they don’t have any jobs available and you need the money.”

Oh, and benefits are an issue: There are none. When someone in McPhee’s family has a medical emergency, as her daughter did just before Christmas, it can be catastrophic.

True north, work uncertain

Linkunatis and McPhee are among a growing group of Canadians doing temp and part-time work.

Last year, about one in 10 employed Canadians was doing temporary work, compared with about 8.6 per cent in 1997, according to Statistics Canada. In that same time, the percentage of people in temporary or contract jobs, specifically (as opposed to seasonal or casual work) was up to 6 from 4 per cent. (Statistics Canada stopped tracking temp agencies in 1997, so data on people working through those agencies is scant.)

For his part, Ken Graham, director of training and professional services at Adecco, says he’s seeing more young people at his agency.

“We tend to see a lot more sort of college grads, university grads showing up on our doorstep looking for work than we would normally,” he said.

“They’re having a really tough time. There’s just not the same number of positions out there.

“… The challenge that we have, from an agency standpoint, is these youth mnay come out of college with theoretical knowledge, but they’re unskilled.”

Whatever the age, Canadians in temp and part-time work are increasingly in that position but would rather not be, according to Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey.

Almost a third of Ontarians working part-time are doing so involuntarily, compared to less than a quarter in 2007. In Manitoba last year, the percentage of people working part time by necessity was at its highest level since 1998.

“What’s really been increasing is the insecurity of jobs,” said McMaster University labour professor Wayne Lewchuk.

That labour uncertainty can be a blow to your paycheque: Last year, the median hourly wage for temp work was 83% what you’d make in a permanent job, down from close to 86% in 2008.

It can also be bad for your health. Lewchuk has written a book exploring the broader implications of precarious work, which extend well beyond the labour itself.

“People in temp agencies have poorer health. And it’s not all because they start with poorer health,” he said.

They’re more stressed, less trained and more likely to be involved in workplace accidents than their permanent counterparts.

“They may not be given the information they need to work safely.”

This precarious lifestyle can hurt individuals’ ability to save, to plan, to raise families, to deal with health emergencies when they’ve no benefits or sick days to fall back on.

Lewchuk has found the inability to plan, or being at the mercy of an agency’s timetable, can take a toll on family and community cohesion.

“What is this doing to families and the next generation of young kids growing up in a household where there’s all this insecurity?”

It doesn’t help that the most obvious government support isn’t available to workers who routinely find themselves between jobs: Changes to Employment Insurance mean you get less money for a shorter period of time the more frequently you need to use the program.

It’s meant to encourage people to find work, even if it means moving to another region of the country. But the result is less support for those who need it most.

Graphic by Janet Cordahi

Fewer than a third of Ontario and Alberta’s unemployed are getting EI; in B.C. and Manitoba, it’s fewer than half.

During the last major recession of the early ’90s, that figure was closer to 80 per cent nationally, says Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives senior economist David Macdonald.

“This isn’t a universal program,” he said. “The folks working odd jobs, working part time, they pay in and they can’t get the benefits. …

“What it means is there’s a much smaller safety net, particularly for folks at the bottom end.”

Precarious labour, uncertain solution

The full-time, permanent workplace is not coming back, Lewchuk says.

“So what do we do about it? … We have a whole set of institutions based on the 1970s labour market and we don’t have a 1970s labour market any more.”

Lewchuk argues government actions so far aren’t helping.

“There’s a sense that somehow the markets going to fix everything here. And it’s not going to fix everything.”

WATCH: Deb Matthews talks to Global News about precarious work

Deb Matthews knows it. Ontario’s Deputy Premier and Treasury Board President has been appointed Minister responsible for the province’s Poverty Reduction Strategy.

So she has a lot on her plate.

“Our economy is changing, make no mistake about it: Some of those manufacturing jobs that we had in the past, that were steady jobs with good income, they’re not here any more.”

In an interview with Global News last fall she cited her government’s child benefit, childcare subsidies and expansion of health care for kids in poverty.

“We know, for some, if you’ve got a child with asthma you might be better off on social assistance than working full time, right? If you’ve got to pay for that drug. So we want to remove that barrier going forward.”

Matthews also called out the federal government’s income-splitting plan, which will overwhelmingly benefit wealthier households.

But there’s no concrete plan to tackle precarious employment.

“Precarious employment is something we have been focused on for some time. … We haven’t fixed that problem. But what we have done is we’ve worked with the advocates in that area to make things better. And we will continue to make things better.”

WATCH: Deb Matthews on education and the ‘welfare wall’

One possibility Lewchuk suggests would be to increase the minimum wage for temp and part-time work – effectively forcing employers to pay for the flexibility and, to a degree, make up for the benefits part-time employees don’t get.

Right now, he said, “employers are getting the flexibility they say they need but they’re not paying the full expense of that flexibility that the workers bear.”

For her part, Linkunatis dreams of opening a restaurant — the kind of comfort food that gives hardworking families a small sense of luxury. She’s still at the business research stage, not ready to apply for a loan yet.

“I’ve been thinking about the food places we have now, thinking, ‘I could do better than what’s out there,'” she says, laughing.

“The experience, the atmosphere. It’s just gotta be right.”

After years of hustling for innumerable temp agencies, she’s ready to be her own boss.

Tell us your story: Have you found yourself trapped in precarious work? We’d love to hear from you.

Note: We may use your response in this or other stories. While we may give you a shout to follow up we won’t publish your contact info.

Comments