Tim Iqbal’s first job in Canada was shovelling snow.

The computer science graduate and his wife, a teacher, had just arrived from Pakistan and needed to pay the bills while they got their skills Canadian certification. So when the temp agency called, he jumped at the chance.

He was decked out in dress pants and fancy shoes, but took off his tie before starting to shovel.

That was eight years ago. A few months after his arrival in Canada in 2006, Iqbal got his first job in IT. Now, he runs his own company – two, actually: solar and IT development and consulting – and mentors new Canadians who find themselves in the same position he and his wife were in.

Except today, the prospects for Canada’s most highly educated new Canadians is far more dismal.

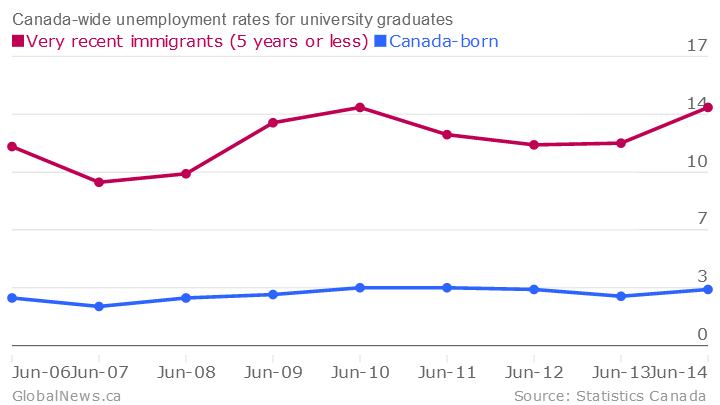

Unemployment levels for recent immigrants with university degrees hit their highest point since June, 2010 last month.

According to data Statistics Canada crunched for Global News, 14 per cent of university-educated immigrants who’ve come to Canada in the last five years are without a job – more than their counterparts with a post-secondary certificate or high-school diploma.

Only 3.3 per cent of Canadian-born university grads, on the other hand, are unemployed, as are 5.6 per cent of university-educated immigrants who’ve been in Canada a decade or more.

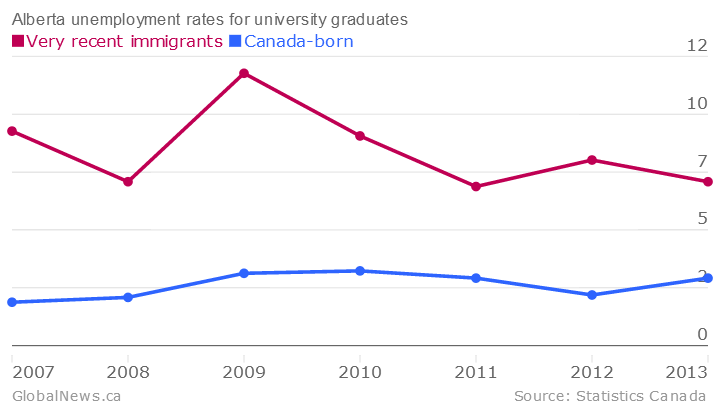

And 2013 numbers indicate Ontario’s swapped places with Quebec as the worst place to be a highly educated new immigrant in search of work: Last year 14.7 per cent of recent immigrants in Ontario with university degrees were out of work, compared to 12.4 per cent in Quebec.

(Note: While Canada-wide numbers are a three-month moving average and include June 2014, provincial statistics are annual and end at 2013)

Get weekly money news

The job picture’s much rosier in Alberta, and although the gap between new Canadians and those who were born here persists, it’s much smaller than elsewhere.

Of course, these numbers don’t count the thousands of newcomers who find work, but not in their field. These under-employed immigrants cost the economy billions annually, economists have estimated: Their skills go under-exploited, their economic potential unreached (they also often take the entry-level positions many younger or less-educated Canadians would otherwise need).

The job market’s ugly in Ontario overall, notes Western University economist Mike Moffatt – so it makes sense that hits more vulnerable parts of the population first. (Young people, too, are bearing the unemployment brunt of the province’s soft economy)

“A lot of other employment indicators have been really weak in Ontario the last calendar year or so,” he said. “It does seem to be disproportionately hurting immigrants. …

“It doesn’t really matter where your credentials are from if nobody’s hiring.”

What is notable, he adds, is that Canadian-born university graduates in Ontario are actually doing okay: The gap between them and their new Canadian counterparts has grown over the past couple of years.

“Normally you’d think the two would move together, and here they’re not.”

Ratna Omidvar‘s been at this long enough you could forgive her frustration. The chair of the board at the Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council (TRIEC) and president of Maytree, Omidvar’s been working to close the chasm between immigrant and Canadian-born unemployment; now that’s it’s yawning wider than ever, safe to say it’s “disappointing.”

“After all the efforts that Canada and Ontario and organizations like ours have made in trying to level the playing field … it’s very disheartening,” she said. “Because despite the great practices we’ve uncovered and promoted, both in terms of hiring and bridging opportunities for immigrants, the two worlds of employers and immigrants often are not on the same page.”

It shouldn’t be news to anyone that Canada’s newcomers enter the labour market with unwarranted disadvantages; if anything, what’s surprising is that employers, advocates and policy-makers have acknowledged the problem for so long yet failed to fix it.

“In spite of all the rhetoric and the discourse around immigrant talent and global skills and a global economy … Canadian employers are remarkably rootbound and fairly, I would say, traditional in their modes of outreach, of selection, of hiring, of assessment,” she said.

Part of the problem is accreditation, and recognizing other countries’ training regimes in regulated Canadian professions.

“Canadian employers discount immigrant experience almost completely.”

So what would she like to see? A national program that does what TRIEC does – matching immigrants with employers or other mentors and helping employers become more inclusive recruiters -would help, she says. Better government incentives, perhaps, could encourage employers to look beyond their own existing networks when hiring.

Until then, “it’s a matter of time and timing,” Omidvar says. When you arrive (hint: recession’s a bad time) and how long you’ve been here.

“Over time … they will climb back up the ladder” to obtain a job that fits their skill sets, she says. In the meantime, newcomers’ skills grow stale as they struggle to establish themselves.

Iqbal’s more optimistic: One of our biggest problems, he says, is a failure to talk about immigrant success stories (that said, as a Mississauga resident who regularly travels to Calgary for work he knows Ontario’s outlook is uglier). Many new Canadians, he says, aren’t aware of the services out there that can help them build skills and professional networks.

“The example I usually use with my fellow new Canadians is that sometimes … you have to take a few steps backward – and then do a high jump.”

Comments