Racism and the lack of primary care providers mean off-reserve First Nations, Metis and Inuit women and girls have poorer health overall compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts, says a study by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Compared with non-Indigenous females, those in the three distinct groups reported a higher prevalence of diagnosed chronic diseases and worse mental health, including mood or anxiety disorders, says the study, which noted Canada’s colonial history of residential schools, forced or coerced sterilization and destruction of traditional lands.

Researchers used data for all females aged 15 to 55 from the annual Canadian Community Health Survey between 2015 and 2020. That amounted to 6,000 people from the three distinct groups and 74,760 non-Indigenous females, all in their reproductive years.

“Indigenous females waited longer for primary care, more used hospital services for non-urgent care and fewer had consultations with dental professionals,” says the study, published Monday in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Co-author of the study Christina Ricci said the study shows the need for change.

“We all need regular, easy-to-get high quality access to care and unfortunately, for Indigenous females, that’s often a struggle to get,” she told Global News in an interview.

“With this study, we’re just hoping to start to understand some of those gaps and work towards steps towards health-care reconciliation and towards equitable health care throughout the country.”

Lead researcher Sebastian Srugo said that while thousands of women across Canada lack a family doctor, “those conversations are happening much, much more among Indigenous women.”

“Even when we compare Indigenous women and people assigned female at birth to non-Indigenous counterparts of a similar age, similar education, income and living in the same places, we still have those gaps,” Srugo said.

While Ricci said the aspect of potential racial discrimination was not specifically touched on in the study, it could be inferred – and based on advice of the Indigenous advisory group involved – the results may speak to that possibility.

A person living in a rural community may face more difficulty accessing care compared to living in an urban centre, she said.

“One could infer that that has to do with systemic racism and a lack of trust in the health-care system,” Ricci said.

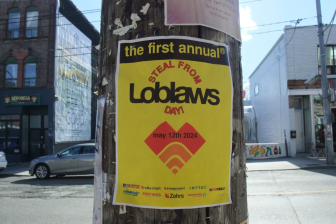

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- As Canada’s tax deadline nears, what happens if you don’t file your return?

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

Women who were pregnant or had just given birth were worse off, and that could affect their children years later, he said.

“This is about intergenerational impacts of not having access to this care,” Srugo said. “It’s also about a justifiable lack of trust that Indigenous communities have with the health-care system in Canada.”

Ricci went on to to say not having access to a permanent health-care provider creates a “major hurdle” for those going through pregnancy, such as being unable to book a gynecological appointment.

“You have potentially that justifiable lack of trust in the health-care system, because you’re removing all the other sort of things that could possibly contribute to why somebody who lives in a certain place is getting better health care than another,” she said.

She added that when people are not able to get that care from a primary care physician, they may be going to the hospital or to the emergency room for issues that are “not immediate.”

As a result, she said the “quality of care is declining.”

Primary care providers could support the women in their reproductive decisions and assess them for conditions including heart disease, depression and cancer, he said.

Multiple studies have connected poorer health outcomes for Indigenous females compared to the wider population.

But Srugo said the PHAC study adds to limited research involving First Nations, Metis and Inuit, which have diverse cultures, languages and histories but are typically lumped together as Indigenous Peoples.

The study included 2,902 First Nations, 2,345 Metis and 742 Inuit women and girls. Researchers also received input from an advisory committee specifically created for the project. Members were from four organizations – Les Femmes Michif Otipemisiwak (Women of the Metis Nation), the Native Women’s Association of Canada, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada and 2 Spirits in Motion.

While Lee Clark, director of health for the Native Women’s Association of Canada, lauded federal researchers for partnering with Indigenous organizations, she said their study should not become “one more paper in the pile of evidence” that has made little difference in the lives of women deprived of equitable care.

Researchers themselves cited the challenges in access to care in a “disjointed jurisdictional system, resulting in medical relocations for birthing and general health care.”

Clark said she hoped the federal government would use the findings to “hold provinces accountable” to deliver targeted programs for women whose needs have been sidelined for too long.

Indigenous communities are still deeply affected by the 2020 death of Atikamekw woman Joyce Echaquan in a Quebec hospital, where she filmed staff insulting her as she lay dying, she said.

“The majority of people I speak with in the community, we have stories of blatant racism,” she said from Gatineau, Que. “Colonialism isn’t historic. It’s ongoing. These harms are continuing and they’re perpetuated still. Joyce’s example is just one of the examples that was recorded.”

In a decision earlier this month, anarbitration tribunal ordered the reinstatement of an orderly who was fired by the hospital. An arbitrator wrote that while the employee made inappropriate comments toward Echaquan, she was not responsible for most of the poor treatment the patient received compared to the “insulting, vulgar, racist and rude remarks and behaviour” of a nurse. That nurse was also fired for telling Echaquan that she was stupid and “better off dead.”

Clark also called on federal and provincial governments to work together to incorporate Indigenous practices in health care, including midwifery that uses traditional practices.

“Pockets of this is happening, recently in Nova Scotia. It needs to be everywhere. It needs to be more accepted. The medicalization of birth is just an outright stamp of colonialism.”

–With files from Sean Previl, Global News

Comments