Climate scientists proclaimed July 3, 2023, the hottest day in human record keeping.

Canada has seen a swathe of heat warnings in the past week, warning of elevated risks for heat-related illnesses and air quality. And the return of El Niño, a naturally occurring climate pattern, is bringing even warmer weather than the country has seen in the past seven years.

But data shows many Canadians don’t have air conditioning.

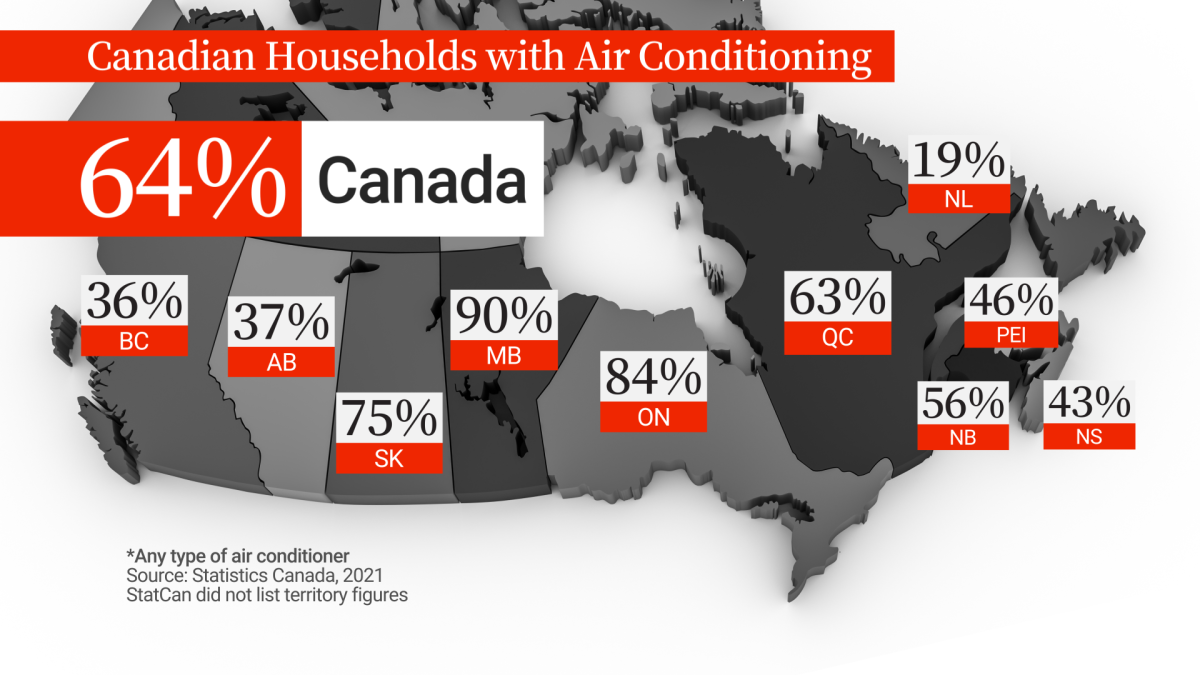

According to Statistics Canada, 64 per cent of Canadian households had some kind of air conditioning in 2021, the most recent year for which figures are available.

The numbers vary by province, as low as 19 per cent in Newfoundland and Labrador and as high as 90 per cent in Manitoba.

Dr. Melissa Lem, president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, told Global News those numbers were likely appropriate, based on local climates, in the past. She said they likely aren’t enough for the future as climate change brings about more heat waves.

“Our bodies are designed to operate in a really narrow temperature range,” she said, speaking from Vancouver, “and when we go past that temperature range, we start to get sick.”

Lem said it’s important for people to have access to cool indoor environments, either in their own homes or via public transit, and to keep in contact with others.

Get weekly health news

“One of the major risk factors for death during the 2021 heat dome on the West Coast was social isolation,” she said, adding that many seniors — who are among those more vulnerable to extreme heat — are socially isolated.

With that said, how we create cooler environments matters too, she noted. Adapting in the wrong way could make things worse.

“People talk about air conditioning as being the solution, but in fact, what’s even more important is electrifying our cooling,” she said.

Using air conditioners, depending on how the electricity powering them is generated, can create more carbon emissions and ultimately raise temperatures even further.

Lem said it’s also important to reduce fossil fuel use.

According to city data, 55 per cent of Vancouver’s carbon emissions come from heating buildings with natural gas.

“If we rapidly retrofit our buildings to electrify and install heat pumps that can cool, that will both keep us safe indoors but also tackle the climate change issue at the same time,” she said.

Using air conditioning can pose further challenges, a University of Waterloo researcher told Global News.

Joanna Eyquem said air conditioning units pump hot air outdoors – just one of the reasons why urban areas can be between 10 to 15 degrees warmer than surrounding rural areas.

Eyquem said the artificial surfaces within cities retain heat and release it in the evening.

Moreover, if many people are using air conditioning during hot weather, the strain on the power grid can heighten the risk of blackouts, which could lead to other problems.

Eyquem’s research showed that the National Building Code does not consider extreme heat to be an emergency. Eyquem said that means most cities or apartment buildings don’t have more than two hours of emergency backup power.

According to Eyquem, adaptation is necessary. That involves preparing homes to keep heat out and cool air in – meaning using things like more awnings and energy-efficient windows.

Outside of households, she said it requires adding more green spaces to cities, limiting the amount of heat-storing concrete and metal, as well as planting more trees that provide shade.

Both Eyquem and Lem said provincial and federal governments must update building codes to ensure living spaces are cooler.

“If we’ve only relied on air conditioning, we haven’t put any of those kinds of passive approaches that really stop heat entering our homes,” Eyquem told Global News.

Eyquem and Lem both said adaptation is ultimately about keeping people safe.

“It’s not just important to start to gradually electrify and start to introduce cooling. This has to be done at speed and scale to make sure that lives are protected,” Lem said.

– with files from The Canadian Press and Reuters

Comments