Members of the celiac and gluten-intolerant community in Nova Scotia say they are struggling amid the rising cost of gluten-free necessities.

Inflation has made the most basic dietary staples, like bread and cereal, up to five times the cost of their gluten counterparts, according to Celiac Canada, the national organization for the autoimmune disease.

“I work full-time, I’m 31 years old, I have a college education, and I would not be able to live on my own,” said Deanna Wilband, who has celiac and recently moved in with her brother in order to support herself and her 10-year-old son.

Wilband, who works for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans as a data coordinator, was diagnosed with celiac disease in 2018, after months of bloating, stomach pain, migraines, rashes, sore throat and fatigue.

She said she’s seen the prices for gluten-free food triple in the last three years.

“I find in the grocery store I have to put things back,” Wilband said.

“I will never buy something myself and put something back for my child. So either I don’t eat, or I’m eating a lot less than I should be eating because I have to sacrifice.”

Wilband said it has gotten so bad at times that her parents have had to buy her groceries or have given her gluten-free snacks as Christmas and birthday presents, which have now become luxuries due to marked-up prices.

Angela Thomson is in a similar position. As the mother of two young children, she frequently has to watch her pocketbook, while trying to ensure her daughter is included despite having celiac.

“Trying to afford the everyday basics for their lunches, for their breakfasts, just their food — it has been really, really, hard,” Thomson said.

Four-year-old Marissa was diagnosed with celiac when she was two years old, after lots of stomach complaints, flu-like symptoms, and weight loss.

Lately, Thomson said making sure both her children have everything they need week-to-week is challenging.

Get daily National news

“I would go to the grocery store and say ‘OK, Zachary needs a box of cereal, but so does Marissa. Well, they both need the cereal.’ So, it’s just frustrating, to have to pick between my kids,” Thomson said through tears.

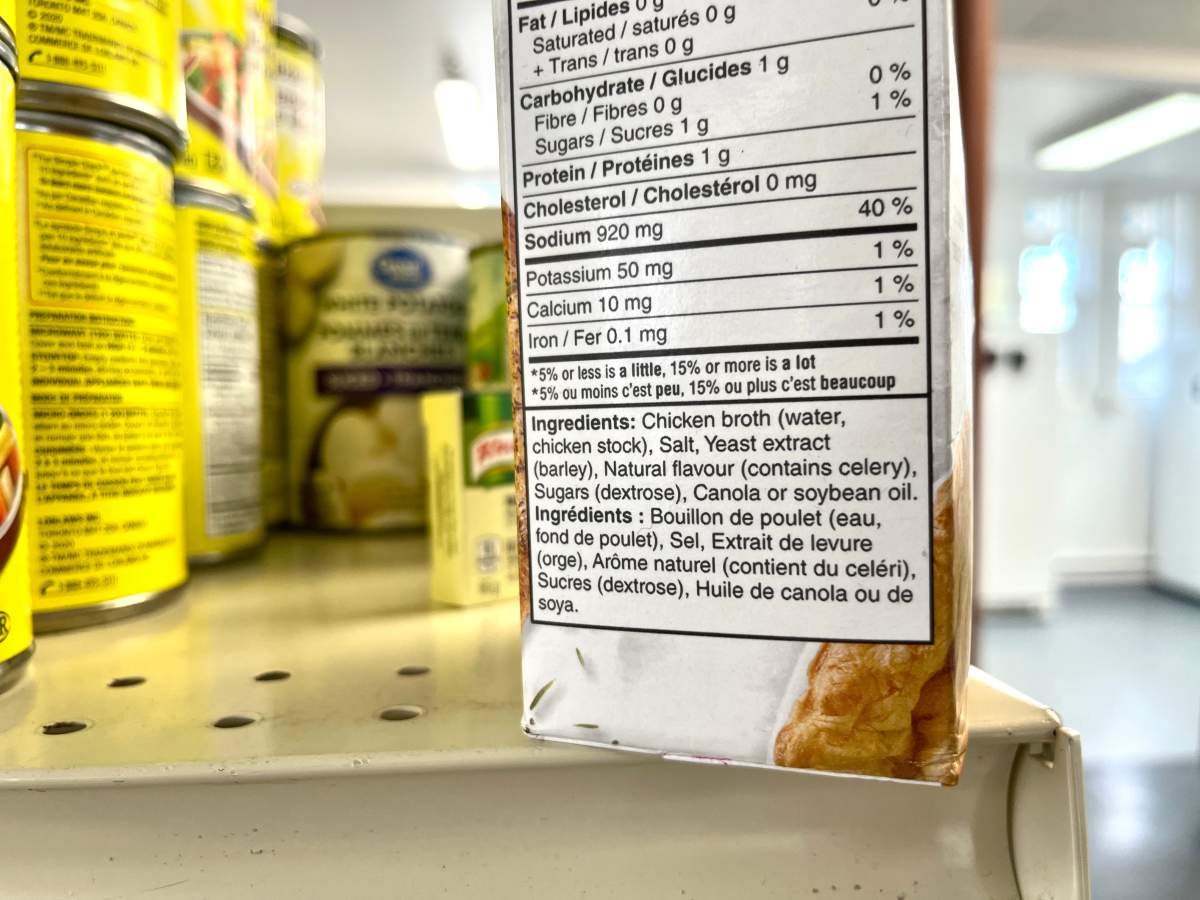

For people like Wilband and Marissa, cutting out the regular gluten-containing products, like wheat, rye, barley, oats, brewer’s yeast, triticale and malt, isn’t enough as cross-contamination could still cause weeks of illness.

Wilband said it takes as little as a crumb for her to get sick, making going out for meals near impossible.

“A lot of the time I’ll just get water. Or I’ll eat my bar while all my friends or my family eat because I can’t risk being sick for two weeks.”

It causes a lot of anxiety, Wilband said, not just out of the house, but also at home where she has to constantly ensure her son’s gluten-containing food doesn’t contaminate her own.

“We have separate utensils, separate toasters, a lot of separation,” Wilband said.

But even extreme diligence is not enough in some cases. A few months ago, Marissa broke out in a full-body celiac-induced rash. Thomson said they went over every exposure Marissa could possibly have.

“We were talking back and forth with the daycare, back and forth with the school, and it finally hit me that she was coming into contact with Play-Doh,” Thomson said.

Thomson said she is constantly trying to make sure Marissa has the same opportunities as her brother. Every school event, celebration and holiday requires planning.

“Going to a birthday party, I have to go and buy a cupcake mix. Well, a cupcake mix with gluten is like $3 or $4. For a gluten-free cake mix, it’s about $8.99, $10,” Thomson said.

According to dietitian Acacia Puddester, even the most basic staples have shot up in price.

“A loaf of gluten-free bread is anywhere from say $6.99 up to $10.99 for one loaf,” she said, adding that she worries that people who can’t afford specialty gluten-free may try to put up with discomfort.

“If they have celiac disease, it is doing damage inside, specifically to their intestine, that they may not be aware of and that damage can prevent your body from absorbing nutrients from other foods for long-term,” Puddester said.

This is on top of the risks of cancer, infertility, as well as other chronic illnesses.

Lisa Harrison, executive director of the Brunswick Street Mission, said its foodbank always tries to have gluten-free food available, but the costs have been rising, limiting access.

“People often make themselves sick by eating food they are not supposed to because it’s all they can get. Speaking as someone who is gluten-free myself, I will sometimes cheat and eat something that’s got gluten in it just because I’m starving,” Harrison said.

Celiac Canada is pushing the federal government for better tax relief for those with celiac disease after many Canadians with celiac said Ottawa’s most recent grocery rebate didn’t go far enough.

“When they announce things like a grocery rebate I’m like, ‘OK, that’s great, that would really help, I could go out and stock up on things and fill the freezer for Marissa,’” Thomson said. “But then I come to find out, ‘No, you don’t qualify because you make too much money.’ Well, how is it that I make too much money and my cupboards are bare most of the time?”

Without the federal support they need, celiac Haligonians will have to get creative when it comes to feeding themselves.

Puddester suggests focusing on foods that are naturally gluten-free in the grain food group, like rice and quinoa, and going to potatoes for much-needed carbohydrates.

She also recommended Haligonians take advantage of the FlashFood app and buy in bulk when possible.

Canadians need to know being gluten-free is not a choice for those who are celiac or gluten-intolerant, Wilband said.

“We will be violently ill, and it causes a lot of heartache, a lot of stress, a lot of anxiety,” she said. “We’re not doing this as a fad, we really are suffering from a disease.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.