TORONTO — The decision to end funding for a program that provides care for patients without health insurance will not be reversed, Ontario’s health minister said Monday as she defended the move that’s come under fire from the province’s doctors.

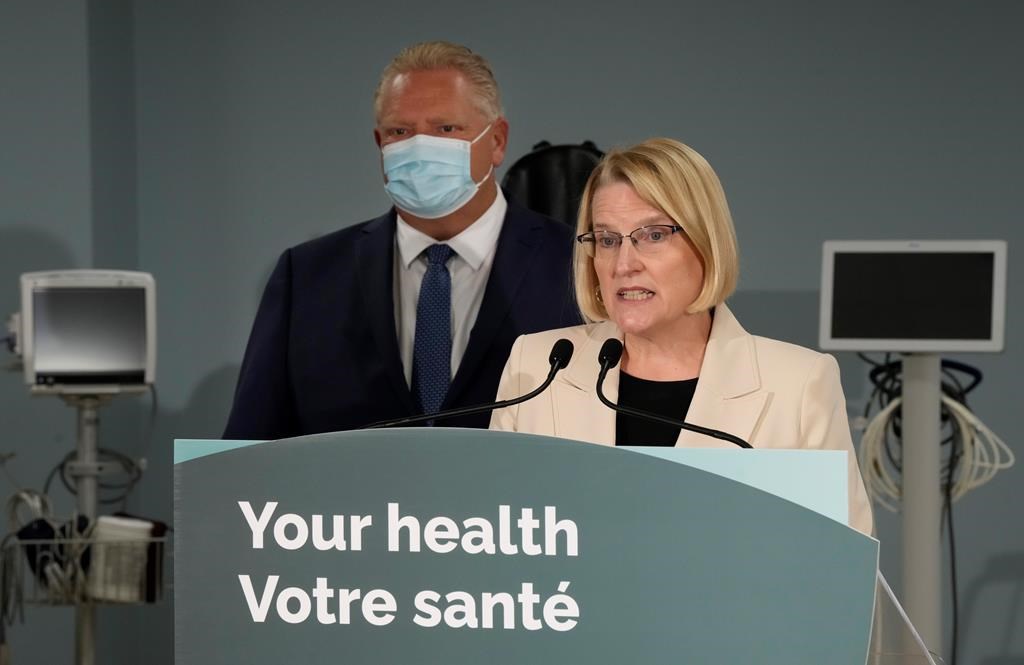

Sylvia Jones said uninsured patients can still receive health care through other programs after the Physician and Hospital Services for Uninsured Persons Program ends this Friday.

“There’s no change in the way that uninsured persons will receive care in the province of Ontario, the only change is how hospitals, community health, and midwifery centres will be reimbursed for ensuring and providing that care,” Jones said in the legislature’s question period on Monday.

Hospitals cannot refuse care to a patient who has a life-threatening emergency and there are community-based programs to help those without a health card get primary care, Jones said.

The province informed Ontario’s doctors about its decision to end the program last Friday, which caught them by surprise.

The Ontario Medical Association had asked for a six-month extension to work on a better solution for the uninsured. Its president said ending the program would be detrimental to those who do not have health coverage.

The association has said those who are uninsured include people who are homeless, those facing language barriers or mobility issues, many newcomers, migrants and international students.

Under the program — introduced in March 2020 when the pandemic hit — 7,000 doctors billed the province for providing some 400,000 patient services, the OMA said.

Get weekly health news

Jones and Dr. Rose Zacharias, the president of the association, spoke by phone over the weekend about the issue.

“The OMA feels the decision to end the program will be detrimental to the livelihood of marginalized Ontarians who often face the greatest barriers in our society,” Zacharias said Monday.

“Instead, the government will rely on the goodwill of physicians who often exercise a moral obligation to care for uninsured persons without being compensated.”

The program cost $6.8 million in 2020-21, $6.3 million in 2021-22 and $2.7 million so far this year, the OMA said.

The association is still asking the government to reverse its decision.

Jones said after question period that the program would not be extended.

She said the program was put in place to help reduce the spread of COVID-19 at a time when movement outside Ontario was restricted due to border closures.

She said there are other programs already in place that can help the uninsured get health care.

“That could be through an emergency department, that can be at over 75 community health care centres that operate in the province of Ontario today, right now, and are funded to ensure that people can get access without an OHIP card,” Jones said.

But those community health centres are not an adequate substitute, said Dr. Michaela Beder, a psychiatrist who works with marginalized patients in Toronto.

“There’s just not enough of them, many, many people will not be able to access care through these centres,” said Beder, who is also part of Healthcare 4 All Coalition, a collective of health-care workers who advocate for permanent access to health care.

“This is a devastating cut _ cutting this program will cause suffering and might cost people their lives.”

Doctors said the soon-to-be-cancelled program has been wildly successful.

The issue of providing care for those without insurance or with lost or expired health cards has been a decades-long problem that the province had seemingly solved with the program, they said.

“The uninsured program was a very welcome and progressive policy to ensure that people could get better access during a global pandemic,” said Dr. Andrew Boozary, the executive director of social medicine at University Health Network.

“You can’t pull this back completely and believe there are not going to be serious consequences for people who are already very marginalized and structurally vulnerable.”

Boozary said the policy helped uninsured individuals feel comfortable enough to go to a clinic to get vaccinated against COVID-19 or to receive treatment for another illness.

“This policy saves lives because it removes barriers,” he said.

Doctors and the OMA are hopeful something can be salvaged by Friday.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.