The number of annual visitors to Alberta’s parks has been steadily rising, sparking a question of how to balance the desire for recreation with environmental concerns.

“Places like Banff National Park and Waterton are being loved to death,” said Jody Hilty, president of Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative.

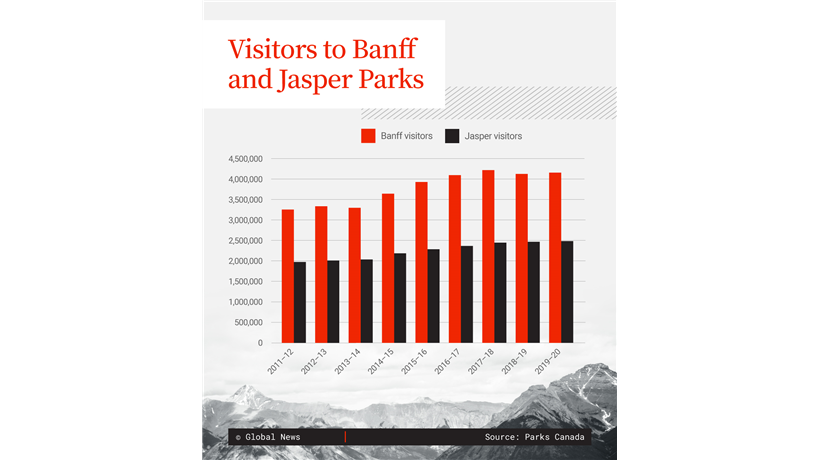

The number of visitors to both Banff and Jasper national parks increased by around 25 per cent from 2011 to 2020.

The Alberta government said the number of visitors to provincial parks, meanwhile, has increased by more than 33 per cent over the last five years.

Hilty’s organization recently released a study that found that about a quarter of trails in the mountains of Alberta and southern B.C. are unmanaged, which can lead to concerns around sensitive wildlife, she said.

“If trails are going through creeks and rivers that have endangered bull trout or other species, it can actually impact the water quality and impact their ability to reproduce,” she said, adding human activity may also cause animals to abandon their dens.

She wonders if the unmanaged trails were created by hikers looking to get away from packed attractions.

“Is it because people just kind of want to toot off on their own and kind of get away from the crowds? We don’t know,” she said.

The influx of visitors to the parks has lead to some government agencies putting conservation above recreation by making changes to how parks can be accessed.

Parks Canada made waves in recent months with the purchase of two backcountry lodges that operated on the habitat of dwindling caribou herds in Jasper National Park.

Then in mid-January, the agency made the decision to restrict personal vehicles on the access road to Moraine Lake near Lake Louise in Banff National Park.

Parks Canada said the parking lot at Moraine Lake — world famous for its picturesque, Instagram-worthy views — was at times full 24 hours a day, requiring around-the-clock staff who turned away as many as 5,000 cars a day.

Cars with disability tags, as well as shuttles, regional transit and commercial vehicles, are still allowed on the road.

Get breaking National news

The agency said the road runs through an important wildlife corridor and this change will reduce stress on animals in the area.

Banff mayor Corrie DiManno said there wasn’t a choice when it came to restricting access to the wildly popular destination.

“When it comes to folks moving around (the town of Banff) and the national park, we know that it’s not going to be sustainable for folks to be able to go to popular destinations by personal vehicle,” she said.

“We simply do not have the road capacity. We don’t have the parking capacity.”

In recent years, the Town of Banff has put out warnings before expected busy periods — like long weekends — that taking private vehicles into the townsite is not recommended.

“So then what becomes the answer? And that is: transit,” said Dimanno.

The town operates Roam Public Transit with 10 routes from Banff to destinations such as Canmore, Moraine Lake, the Banff Gondola and Johnston Canyon.

“Parking lots fill up really quickly in the morning and you’re not promised a spot, but you can reserve on a lot of the shuttles,” said Dimanno, adding shuttles are the only way tourists can guarantee they’ll see the sights.

Other changes to how Banff National Park is accessed are sorely needed, according to a panel convened to make recommendations on sustainable transportation in the park.

Last summer it cost $12.25 to park a vehicle at the Lake Louise lakeshore for the day.

Meanwhile, the Parks Canada shuttle tickets are priced at $8 per adult plus $3-$6 for a booking fee and the fare for Roam Transit’s Lake Louise route is $10 per adult with an hour-long transfer period.

This means it’s cheaper to drive and split parking spots with friends than to take the shuttle — but it’s time for that to change, according to a report detailing the findings of the panel.

“Pricing should make public transit more attractive and personal vehicle use less so.”

In the next few weeks, this year’s parking fee for Lake Louise will be determined and announced, according to a Parks Canada representative.

The report suggested charging more to access the park in a private vehicle than via public transit.

Apart from pricing disparities, the report said there are other reasons visitors will be unlikely to ditch their personal car — mass transit lacks facilities to carry sporting equipment and strollers, and the system has holes that affect connectivity.

Banff is not the first park to consider restricting or changing access in the name of conservation — Lake O’Hara in B.C.’s Yoho National Park has long required visitors to pre-register for shuttles from a nearby parking lot to the pristine and popular lake.

Three popular provincial parks in B.C. — Golden Ears, Joffre Lake and three trailheads at Garibaldi — require day-use passes during peak times.

Nancy DaDalt, director of visitor experience for Banff & Lake Louise Tourism, said a tourist’s experience won’t be the same today as it was 10 years ago, when it was easy to spontaneously show up to the parks and be able to access anything without a huge wait.

DaDalt said tourists are now going to need to plan ahead when visiting.

“Make your reservation and ensure that you can see everything, and then come and see us at the visitor center so we can then fill in some of those gaps,” she said, adding the agency can recommend less popular attractions that may be less crowded.

DeDalt also recommends Albertans take the opportunity to visit the parks in the off-season — when international tourists aren’t likely to be visiting — and even to consider evening visits in the summer.

“Where else in the world can you go that it’s light until 10:30 p.m.? You can arrive at four in the afternoon when everybody else is heading back to their hotel and you’re just heading into those locations because you can still get back to Calgary with lots of light by 9:30 at night,” she said.

Hilty said visitors need to make careful changes to the way they access the park so it stays enjoyable.

“Sometimes that kind of takes people off guard — their experience was they could do anything, because there were very few people when they were growing up and they want that same thing for their kids,” she said.

“That’s a real challenge — we can’t do that when we have so many more people out on the landscape.”

Comments