TORONTO – Seeing a pregnant women smoking a cigarette, imbibing a glass of wine or using drugs is sure to raise a societal eyebrow.

But a new report says women with substance abuse problems should be treated with compassion by health providers and society at large, especially during pregnancy, because addiction is a brain disorder and not a personal failing.

“It’s harmful for us to look upon pregnant women with addiction issues and assume it’s as simple as saying: ‘For the sake of the baby, stop using,”‘ said Colleen Dell, research chair in substance abuse at the University of Saskatchewan.

Dell was among a trio of experts discussing a report by the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA) released Monday in Ottawa, which calls on health professionals to provide non-judgmental information to women about the dangers to themselves and their newborns from substance abuse during pregnancy.

Read more: Childbirth economics: What older moms and teenage pregnancy say about opportunity in Ontario

The report shows smoking, drinking and drug use while pregnant are significant problems in Canada and worldwide. The 2008 Canadian Perinatal Health report found 13 per cent of pregnant women admitted to previous-month cigarette smoking; 11 per cent said they had consumed alcohol; and five per cent reported using drugs.

Monday’s report also cited cases of newborn withdrawal arising from a mother’s drug use during pregnancy. In Ontario, the number of cases of neonatal abstinence syndrome, or NAS, jumped to 654 in 2010 from 171 in 2003 – an almost four-fold increase.

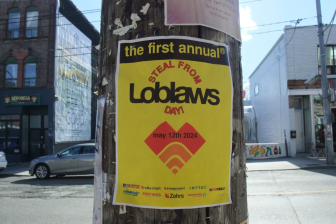

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

Substance abuse during pregnancy can lead to other complications for babies, including premature birth, low birth weight and sudden infant death syndrome. Children can be left with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder as well as other developmental and cognitive difficulties. Such problems can persist into childhood and adulthood.

“Babies born to chronic opioid users, such as heroin or prescription drugs, are often born with physiological dependence to the drug,” said Dr. Loretta Finnegan, who authored the report.

Read more: Toronto hospital launching

“Withdrawal symptoms after birth, though not lethal, affect vital functions in the neonatal period that affect growth and normalcy such as feeding, elimination and sleep,” added Finnegan, founder and former director of the Family Center, Comprehensive Services for Pregnant Drug Dependent Women in Philadelphia.

The report says pregnancy offers an opportunity for doctors to help women seek treatment for addiction, while providing comprehensive care aimed at maximizing the health of both mother and baby.

That treatment should involve a wide range of care providers and programs, including addiction counselling, medication-assisted therapy and community resources for parents, the report says.

“When this continuum of care is provided, we see healthier babies and fewer premature births, and overall maternal and infant mortality rates go down,” said Finnegan.

But many women are hesitant to seek treatment because of the stigma around using a substance that’s known to be harmful to their developing fetus, she said.

It’s important to look at the antecedents to drug addiction, said Finnegan, noting that about 98 per cent of the women in her clinic had been sexually or physically abused as children or as adults.

“This is very much like PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). They have had trauma and taking a drug permits them to forget these terrible feelings that they have had. When they take the psychoactive drugs … they become addicted.

“So the first step is that we get them into treatment and help them feel welcome.”

Often women also won’t seek medical help because they’re afraid of losing their children to protective services if they admit to an addiction, she said, suggesting the judicial system has to change.

Dealing with stigma is the greatest challenge in trying to help pregnant women with an addiction, said Franco Vaccarino, a professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Toronto and chairman of the CCSA’s scientific advisory council.

“Addiction is a disorder of the brain,” he stressed.

“Simply put, your brain is different after prolonged substance abuse than it was before. Addiction fundamentally changes neurological functioning and it makes it next to impossible to just quit for the sake of the baby without significant supports.

“The challenge is anchoring the narrative of this discussion in health terms,” Vaccarino said. “If you anchor it in health terms and move it away from justice and moral and will-related issues, you focus the narrative around addiction, which is where it should be.”

Comments