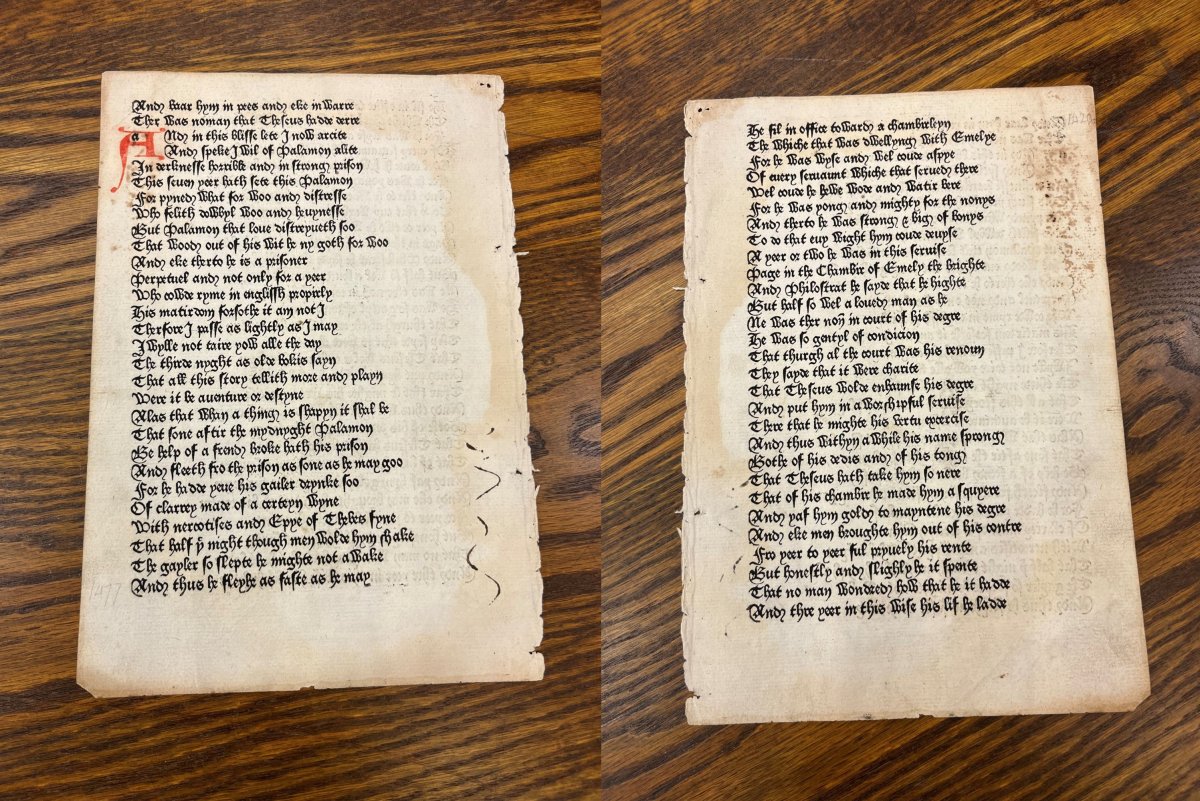

Nearly 550 years ago, William Caxton made history when he established the first printing press in England and used it to produce copies of the country’s first printed books: The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer.

More than half a millennium later, a leaf from one of those copies has found its way into the collection of Western University.

It’s not clear exactly how many copies Caxton printed of the book in 1476, but it’s estimated that about 10 complete first edition copies exist today, along with roughly three dozen fragments or individual pages in collections around the world, according to Western.

The university acquired its Caxton leaf from a well known U.K.-based vendor, Peter Harrington, who had exhibited the rare piece at Toronto’s Antiquarian Book Fair, said Deborah Meert-Williston, a special collections librarian with Western Libraries’ Archives and Special Collections.

Harrington had invited Meert-Williston to see the leaf in exhibition, but she says she was unable to attend.

“Even though I wasn’t going to the book sale, that caught my attention, and I reached out to Peter Harrington and I said, ‘Is it for sale or is it just an exhibit item?’ And they said, ‘Well, it could be for sale.'”

- Trudeau says ‘good luck’ to Saskatchewan premier in carbon price spat

- Canadians more likely to eat food past best-before date. What are the risks?

- Hundreds mourn 16-year-old Halifax homicide victim: ‘The youth are feeling it’

- On the ‘frontline’: Toronto-area residents hiring security firms to fight auto theft

A price was ultimately negotiated, with Western paying roughly CAD$20,000 to $25,000 to acquire the leaf, including an educational discount, she said. A complete copy of The Canterbury Tales would likely fetch well over $1 million.

The Caxton leaf joins six incunabula (a book printed before 1501) already in Western’s collection, donated to the school in 1918 by the university’s first librarian, John Davis Barnett. The Caxton print represents a pivotal time in the history of the printed word, she said.

The transition came when Johannes Gutenberg of Germany introduced the first metal movable-type printing press in Europe in the mid 15th century, ushering in a new era of communication and sparking the proliferation of printing presses around the world.

“It changed the world in the same way like the Internet changed the world in the 1990s because of the access it provided to information,” Meert-Williston said. Gutenberg is also known for the Gutenberg Bible, his printing of the Vulgate, the 4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

Before the printing press, manuscripts had to be made by hand, a laborious and expensive process. As a result, “not a lot of people had access to books,” she said.

“Movable type now allowed us to start printing things. There was some printing before, but you always had to carve a full page or a picture or an illustration into a block of wood or some other type of metal or substrate to print something. It was very, very time-consuming,” she said.

“This just kind of changed everything in Europe and then across the world, to have this movable type replace block printing.”

Caxton, Meert-Willison says, “immediately saw this and understood the value of this,” and adopted the process, printing the world’s first book in English, The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, in 1473 in Belgium.

“Then he decided he was going to go to England, because nobody was printing in England, and he wanted to take advantage of the situation. We think he printed probably a few small things first, some pamphlets, broadsides, things like that,” she said.

“But he wanted to do a great work, and his first choice for a book was The Canterbury Tales. It was very popular… Everybody, kind of, knew (it) through plays or hearing about those stories. But very few people could ever own one because you’d have to own one that was a medieval manuscript.”

Meert-Williston guesses that Caxton may have printed about 600 copies of The Canterbury Tales, however an exact figure is not known. It was from one of those copies that Western’s leaf originates. A second edition of the book was printed a few years later.

“It was a very important book in the Middle Ages, and it continues to be an important book today. There was a movie made about one of the stories recently,” she said, referring to The Knight’s Tale, the first story in The Canterbury Tales, which inspired the 2001 film A Knight’s Tale. Western’s leaf contains lines from the story.

“I really loved that we were getting another incunabula, that we were getting one that everybody would recognize, because the other six that we have, a lot of students wouldn’t really recognize it… And even though it’s a single leaf, what it represents is just so much greater than that.”

Early and rare books and medieval manuscripts often get taken apart and sold page by page. It’s likely that’s what happened with Western’s Caxton leaf, Meert-Williston said.

“We have had other medieval manuscript leads that we’ve been able to find which book they came from and put them back together digitally, even though the leaves live all over the world. So that’s possible with this leaf. That’s for the scholars to do,” she said.

Western officials say the historic leaf will be used as a hands-on learning tool for students at the university studying medieval literature, book preservation, and others.

In a statement, Richard Moll, professor and medieval studies program director, said he would integrate the Caxton print into his course on medieval studies.

“For teaching, it’s fantastic. There is great joy for students when they look at these physical examples. There’s an immediacy to seeing how, in the late 1400s, they were consuming Chaucer,” he said.

Meert-Willison says the leaf will also find use by researchers studying rare books and incunabula, focusing on text layout and paper quality. First edition copies sometimes differ slightly from one another, she said.

“The monetary value of our collection isn’t really what we focus on at all. It’s the research and teaching value from our collection,” she said.

“That’s kind of where our focus is, is what’s the value for teaching and research? I’ve already had this particular item, the Caxton leaf, booked into five classes over the next two months, so it is already popular and will get well-used.”

Comments