In Europe, global warming has been a mixed blessing this winter.

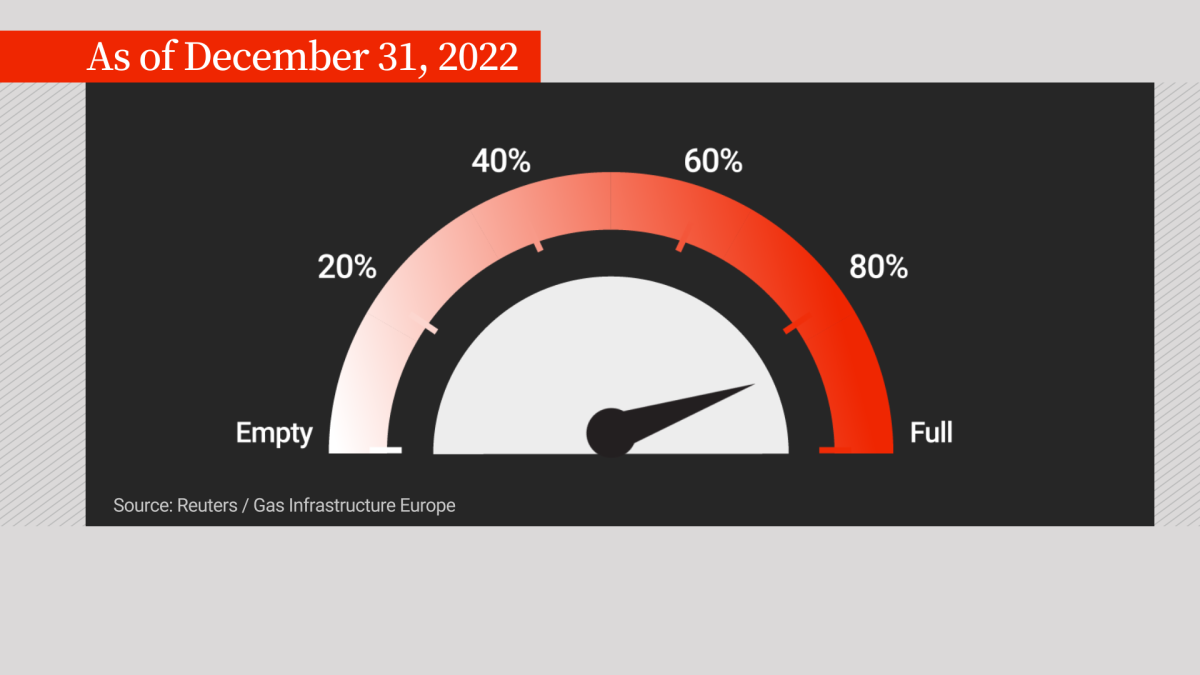

Fears of a massive energy crunch leaving millions of homes in the dark have largely dissipated, at least for now. The European Union’s reserves of natural gas are at least 83 per cent full, and gas prices are a fifth of what they were in August, as supply outstrips demand.

Don’t get your hopes up about Europe’s lower energy prices coming to Canada, though. Experts forecast volatility – energy price swings up and down – to continue for several years, and that’s not great news for consumers.

Energy volatility, says Andreas Goldthau, a public policy professor at the University of Erfurt in Germany, is not good for anyone, from businesses to individual consumers. He says that energy prices that are stable and affordable, is “what, in the end, benefits consumers, because industry can plan, businesses can plan.”

Unreliable or unstable energy supply, in other words, costs businesses money – which gets passed down to the average person, Goldthau explains.

Price swings

Supply and demand for energy are affected by a range of factors that cause constant ups and downs in prices. Those factors include everything from weather to refinery shutdowns, to the political whims of dictators.

While energy might be cheaper in Europe right now, that doesn’t mean it will last.

“Anything can happen,” says Philip Andrews-Speed, a U.K.-based energy policy specialist at the National University of Singapore. “You just need one thing to change again, and (prices) can go up again.”

The upshot?

Energy volatility may be bad for consumers in the short term, but experts say it’s evidence of a global energy landscape that’s changing – toward more diverse sources of energy and, importantly, a more reliable domestic energy supply.

Energy transition in action

Get breaking National news

Vladimir Putin’s fortunes have long been made by relying on fuel exports, including to nearby Germany. But Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has had one unintended consequence: the shift toward clean energy.

“There’s no looking back for Russian gas,” Goldthau says.

That doesn’t mean that Germany’s dependence on natural gas will disappear overnight. But the war has been a wake-up call that countries can get into trouble very quickly if their energy security depends on another country, especially a hostile one like Russia.

Goldthau says that energy – electricity, as well as the hydrocarbon molecules contained in fossil fuels like oil and gas – isn’t simply a commodity traded on the market. Energy, he says, gives countries a distinct geopolitical advantage.

“It has become absolutely crystal clear that electrons and molecules are not only a commodity, they’re a strategic good.”

If Germany avoids the worst this winter, that’ll be in part thanks to Mother Nature, but also to energy conservation measures. The German government is also practicing a modern form of realpolitik: almost more than any other country, it’s shifted away from fossil fuels to a domestic supply of renewable energy.

In Germany, about 40 per cent of the power system was ‘fueled’ by wind and solar in 2021, and that’s only going to increase.

With renewables, says Hari Seshasayee, an energy expert, and trade advisor for the government of Colombia, “you have a lot more control on how much supply you’re going to get over the course of a year, you know what your installed capacity is,” even with the intermittency issues around the availability of wind and sun.

“You don’t have to depend on external factors as much as you would for fossil fuels,” Seshasayee says.

Unfortunately, the price swings will continue, he says, until world energy markets adapt to the transition from fossil fuels to cleaner sources.

“We’re facing probably a decade or so of very volatile commodity prices when it comes to fossil fuels,” Goldthau concurs.

An ‘outcome’ of change

“It’s really not easy to transition from something the world has been dependent on for half a century or more,” Seshasayee says.

The existence of market volatility, however, shows that the world is moving away from fossil fuels, trying to figure out what the energy mix of the future will look like.

“Because if we were continuing to depend on fossil fuels to the same extent as we have over the past few decades, you may not see this much volatility.”

For some analysts, though, that transition is happening without taking into account the importance of maintaining a stable source of energy, first and foremost.

“We do not have enough lithium in this world. We do not have enough copper,” insists Laura Lau, an analyst with Brompton Funds in Toronto, referring to elements needed for the clean-energy transition.

She fears that politicians are foisting a transition onto people without having a good-enough plan to replace existing sources. The world, she says, needs energy, and you can’t just cut off what is available without having something else to make up for the shortfall.

“In an energy-constrained world, we still need energy to grow our economies.”

The future of energy

That’s not so much a challenge in Canada, a country that has vast stores of cheap, reliable energy, mostly oil and gas, but also electricity, about 60 per cent of which is generated from renewable sources.

In many countries, the tradeoff between energy security and energy transition is political upheaval.

If the lights go out, or if people go bankrupt because their energy bills are too high, “you will be met with social unrest … and that’s not what you want,” Goldthau says.

That doesn’t mean that the world can’t keep relying on fossil fuels for a while to keep the lights on, while simultaneously building windmills and solar panels as fast as possible. “It’s both things together,” points out Andrews-Speed.

“The construction of renewable energy will continue apace, and it is being accelerated this year.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.