By

Jamie Mauracher &

Teresa Wright

Global News

Published October 10, 2022

8 min read

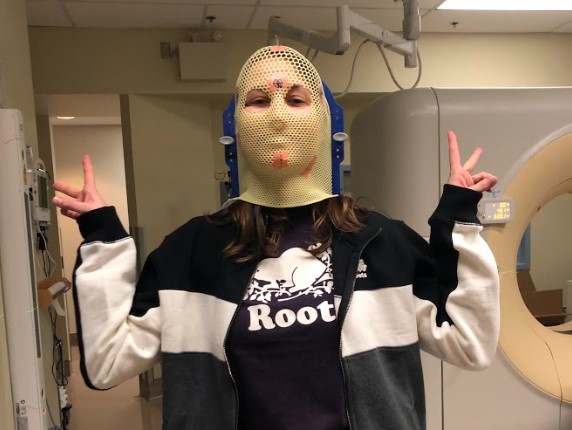

Four years ago, Ontarian Rebecca Grundy got a nightmare diagnosis that sent her into a blind panic.

She was only 28 years old and had no reason to believe she was anything other than perfectly healthy, except for a few headaches.

But after waking up on a stretcher in the hallway of a Toronto hospital after suffering three grand mal seizures, doctors found a cancerous tumour the size of her fist on the front left lobe of her brain.

“As soon as I was told, everything closed in around me… I felt like the floor was falling beneath me and the world was just spinning around. And I literally couldn’t see out of the tears that were coming down my face,” she said.

“In that moment, my life was changed forever.”

Her diagnosis: grade four glioblastoma, an extremely aggressive form of brain cancer with one of the lowest survival rates — typically less than 18 months.

And it’s not usually seen in adults under the age of 45.

When it comes to treating cancer in Canada, it turns out that age does matter.

The drug Grundy needed to survive, an at-home chemotherapy treatment called Temozolomide, is not covered provincially for patients of her age.

As shocking as it may seem, for cancer patients under the age of 65 in Ontario, provincial drug programs only cover intravenous chemo administered in hospitals.

Patients who are prescribed in-hospital treatments can start taking them as quickly as they are needed, in some cases within two weeks, according to the CanCertainty Coalition, a group of more than 30 Canadian patient groups, charities and caregiver organizations that work to improve affordability and accessibility of cancer treatment.

But patients who would benefit from more targeted treatments administered at home in pill form or by self-injection face a “maze of prescription drug coverage programs,” the coalition says.

People diagnosed with cancer under the age of 65 must navigate their own funding solutions for these life-saving medications, as Ontario’s public coverage only includes individuals over 65 and under 25 and those on social services.

That is a huge subsection of people — with a gap of 40 years — who are not eligible for the appropriate care.

A similar situation exists in Atlantic Canada, where public drug insurance plans are designed to support patients only on social assistance or those 65 and older, according to a 2022 study on disparities in public cancer drug funding by Dalhousie Medical Department oncologists Dr. Stephanie Snow and Dr. Ceilidh MacPhail.

Young adults who would benefit from at-home therapies – many of which are newer, more targeted and come with fewer side effects – must first exhaust all private insurance options, and many younger Canadians are uninsured or underinsured.

A 2021 study conducted by the pharmaceutical pricing consultancy PDCI Market Access found 17 to 30 per cent of cancer patients aged 25 to–64 in Ontario have no form of drug coverage whatsoever.

Those patients are left to navigate complex bureaucratic red tape as they attempt to apply to emergency or high-cost provincial drug programs, or to compassionate programs provided by pharmaceutical manufacturers to avoid eye-popping medical bills.

All of this paperwork takes time, and a vast amount of already-depleted energy to complete.

Needless to say, for Grundy, both time and energy were in short supply after her rare-cancer diagnosis.

“I would have to jump through all of these hoops as a young person under the age of 65 to get access to this treatment that is supposed to kill the cancer cells and save my life. And that’s just not fair,” she said.

She spent weeks waiting for provincial assistance. In fact, trying to find a way to pay for her medications was more stressful than recovering from the brain surgery she underwent to have the tumor removed, Grundy said.

“This is a time that I should have been focusing on my wellness, and instead I had to fight for the treatment when I really should have been fighting for my life.”

Meanwhile, in Quebec, where all adults are mandated to have private or public drug insurance, oral cancer drugs are covered and treated the same as hospital-administered therapies.

Patients who live in western provinces have their cancer drugs paid for by the provincial government regardless of their age, socioeconomic status or the drug’s route of administration, according to the PDCI Market Access study.

The disparity that exists among provinces when it comes to cancer drug coverage for younger Canadian patients is why many have been calling for a national cancer drug formulary, – or the acceleration of a long-promised national, universal pharmacare program.

Dr. Snow, one of the oncologists who conducted the Dalhousie study, says the hurdles younger patients have to jump through to get access to more targeted, at-home therapies means some young Canadian adults with cancer are not getting the best treatment and are being exposed to greater toxicities from the drugs that are actually covered.

“That’s the most devastating situation — when the most effective, the most convenient, the best- tolerated treatment just no longer becomes an option,” she said.

For those who try to fight for the more targeted therapies, in addition to the added burden of paperwork and bureaucracy, it often means significant co-pays.

Some are forced to mortgage their homes, some must try to raise money through fundraisers and those trying to use private insurance are often met with roadblocks due to their decreased ability to work, which can affect coverage levels, Snow said.

All of this takes time, energy and resources away from healing, and before long all of this stress is snowballing out of control.

For young patients given a grim diagnosis of a few months or years to live, it’s a devastating situation. Many have young families and are earlier on in their careers and thus have fewer resources available to them, Snow said.

“It means for some people, they’ll take their drugs every second day, they’ll not take them the way they’re supposed to,” she said.

“And that’s really devastating because there should be no difference on what drugs you get no matter where you are in Canada.”

Even in Western Canada, which is considered by many cancer treatment specialists and advocates to be ahead of the curve when it comes to drug coverage, this access comes with caveats.

Megan Goett, 36, was diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer last year.

She was prescribed the chemotherapy drug Lynparza, another at-home medication with less severe side effects.

But in Alberta — where Goett and her young family live — the $8,500-a-month cost is only covered for ovarian and prostate cancers.

Without her husband’s private insurance, the mother of one says she likely wouldn’t be alive today.

“I was really, really scared at that time that I wasn’t going to be able to see (my son) graduate kindergarten,” she said.

“Thanks to this drug… and the fact of how amazing it is working for me has extended my longevity by quite a bit.”

Not only does Goett have Stage 4 breast cancer that spread throughout her body after undergoing a double mastectomy, she also tested positive for the BRCA gene, which means she is at an increased risk of developing multiple cancers.

That’s why the extension of life she has been given by her medication is “everything.”

“It means more birthdays, more memories, just more milestones that I’m able to create,” Goett said.

MJ DeCoteau of Rethink Breast Cancer, a charity and advocacy organization for breast cancer patients, says many younger cancer patients are more likely to be diagnosed with aggressive forms of cancer, which means time is of the essence for treatment.

They shouldn’t have to be using precious time they should be spending with family “jumping through bureaucratic hoops” to pay for the best possible treatments, she said.

The problem, she says, is that provincial cancer treatment systems and the organizations responsible for approving medications for coverage for different types of cancer and different age groups have not kept pace with the evolution of drug therapies.

Her group has been lobbying governments, including the Ontario provincial government, to move more quickly to approve new forms of cancer treatments.

But progress has been slow.

“We’re frustrated,” DeCoteau said.

“We had hoped that our cancer care system would have evolved and tried to keep pace with how cancer treatment is changing.”

Canadian cancer patients between the ages of 25 and 65 who are fighting for their lives don’t have time to wait for the slow wheels of government to move in their favour.

That’s why many advocacy organizations like Rethink have been pushing for more rapid progress in approving life-saving therapies to be more widely available —- therapies that are already approved and listed in provincial drug formularies, but are more difficult and expensive to access for younger cancer patients.

“We’ve been calling for change. We’ve been calling for equal funding for take-home cancer treatments,” DeCouteau said.

“It shouldn’t matter how old you are. Young people shouldn’t be punished and risk higher rates of recurrence, higher rates of dying from their cancer.”

—

Against All Odds: Young Canadians & Cancer’ is a biweekly ongoing Global News series looking at the realities young adults face when they receive a cancer diagnosis.

Examining issues like institutional and familial support, medicine and accessibility, any roadblocks as well as positive developments in the space, the series shines a light on what it’s like to deal with the life-changing disease.

Comments