Canada still faces its own disparities in abortion access and may struggle to act as a “safe haven” for Americans impacted by the overturning of Roe v. Wade, advocates north of the border say.

Although Canadian officials are promising to ensure abortion access and have committed some funding to that effort, experts say more needs to be done to reduce the stigma surrounding the procedure and incentivize provinces and territories to offer care.

“What happened in the U.S. is very scary, and it’s certainly something we have to be vigilant about,” said Insiya Mankani, public affairs officer for Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights.

“At the same time, we need to continue to make sure that there is better access to abortion across this country. And I think the federal government can certainly play a role in that.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Friday promised to defend abortion rights in Canada and around the world after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling that guaranteed the constitutional right to an abortion.

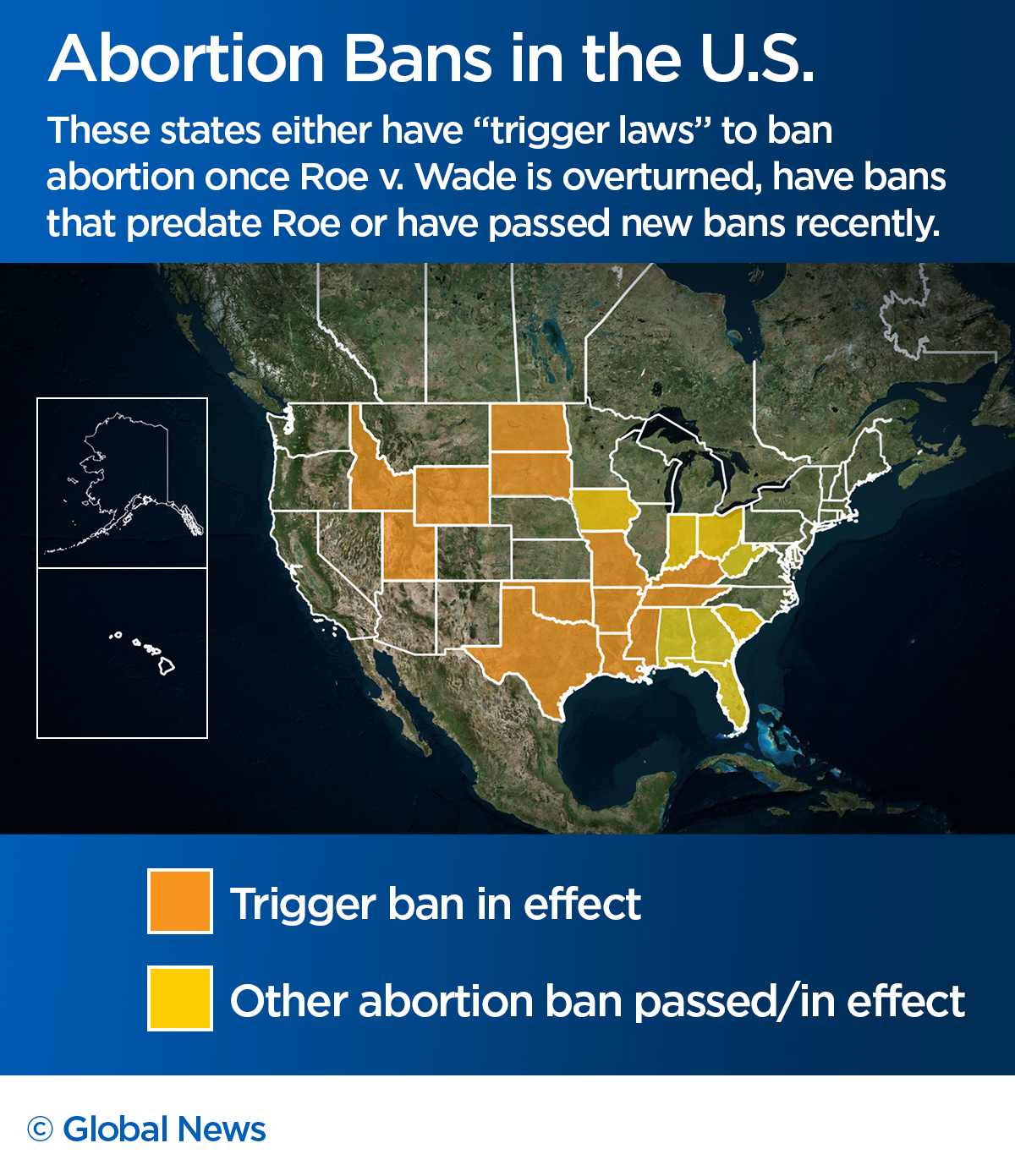

He called the court’s decision a “devastating setback” for American women, who will now face tremendous disparities in access depending on which state they live in. Several states moved immediately to ban abortions in the hours after the ruling.

“Quite frankly, it’s an attack on everyone’s freedoms and rights,” Trudeau said from the Commonwealth summit in Kigali, Rwanda.

“It shows how much standing up and fighting for rights matters every day, that we can’t take anything for granted.”

Abortion is decriminalized in Canada because of a 1988 Supreme Court decision, but no bill has ever been passed to enshrine access into law.

Yet access varies greatly across the country. Women in rural areas of some provinces — including Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba — are forced to travel to urban centres for surgical abortions.

Abortion pills can also be difficult to obtain, as they are not prescribed by family doctors or walk-in clinics.

Though the U.S. decision is sending “shock waves” everywhere, the legal ability to have an abortion in Canada is not under threat, said Joyce Arthur, executive director of the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada.

Get weekly health news

But her organization is concerned about Americans coming north for abortion care and is advocating for federal and provincial governments to help clinics with more funding because, as Arthur puts it, “even a small number of Americans can overwhelm our system.”

Mankani could not say how many women advocates expect to cross the border for care.

Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino said last month he would be speaking with the Canada Border Services Agency to make sure its staff know Americans seeking abortions can come to Canada.

Dr. Martha Paynter, a registered nurse working in abortion care and a post-doctoral fellow with UBC’s contraception and abortion research team, told Global News clinics across the country may see an increased demand.

“And of course, we will care for them,” she said.

But she warned Americans will face “significant costs” as a result.

“They do not have provincial health insurance and will have to pay for their care if they come to Canada to seek it,” Paynter said.

Not all parts of Canada are likely to see a surge from the United States.

Western states like Washington, Oregon and California are moving to protect abortion rights and promote themselves as safe havens, while abortion rights bills have been passed in states like New York and the surrounding northeast.

That means British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes are unlikely to see a “significant” spillover, Dr. Dustin Costescu, an associate professor at McMaster University as well as a family planning and sexual health specialist, previously told Global News.

Yet the Prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba — which already struggle with access — could see Americans coming from states like Idaho, North Dakota and South Dakota, which have banned abortion through “trigger laws” that went into effect after the Supreme Court ruling.

- Ontario government home care vendor paid ransom to regain access to its servers: report

- Concerns over capacity at Vernon hospital psych ward after young man’s death

- Manitoba government proposes health charter but Opposition questions effectiveness

- Nova Scotia only faith-based hospital to end religious sponsorship

No need for a national law in Canada

Although the right to an abortion doesn’t exist in Canada in the same way it was once enshrined in Roe v. Wade, experts say a national law or similar legal precedent would likely backfire.

“It is not within the Criminal Code, and that is actually a good thing because it means subsequent governments cannot overturn any ruling, suddenly making it very restrictive,” Mankani said.

“It lives within the Canada Health Act as a piece of health care, because it is health care.”

Mankani says instead, the Liberal government should focus on fulfilling its election promise to create Canada Health Act regulations that would penalize provinces for failing to provide access to sexual and reproductive health services.

Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos told reporters in May such mechanisms already exist, but his officials were looking at reinforcing them in the coming months.

Last year, the Liberal government confirmed it had withheld about $140,000 of New Brunswick’s share of the federal health transfer because it does not fund abortions provided at a clinic in Fredericton.

Another priority, Mankani says, should be the creation of a government-run web portal that can direct women seeking an abortion to proper information, their closest provider or how to access abortion pills.

While Action Canada and other advocates provide similar services, she said these groups survive through donations and are a “stopgap” for a more permanent solution.

“The lack of access to accurate information in Canada is a huge barrier for people seeking abortion care,” she said.

Ottawa has provided $3.5 million to Action Canada and the National Abortion Federation to improve their efforts to provide information and support to women seeking care.

Mankani says while the news out of the U.S. is “devastating,” she’s heartened that organizations and advocates are stepping up to ensure rights aren’t scaled back elsewhere.

“There is that devastation, but there is certainly that hope for change as well,” she said.

— with files from Global’s Amy Judd, Amanda Connolly and the Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.