The presence of ancient multi-tools in southern Africa may suggest that communication between ancient humans spanned long distances, according to a study published in Scientific Reports on Thursday.

But ancient humans weren’t only talking to each other, the research found, they were also sharing knowledge that may have aided in the overall survival of the human race.

The Howiesons Poort blade is known as the “stone Swiss Army knife” of prehistory because it is an early example of a composite tool that had multiple purposes. While stone tools were not revolutionary for the time, the Howiesons Poort blades were so groundbreaking because they are ‘hafted‘ — meaning that the stone blades are affixed to handles — using glue and adhesives.

Ancient humans in southern Africa produced these early multi-tools in large numbers for hunting (fashioned into spears and arrows) and cutting wood, plants, bone, skin, feathers and flesh.

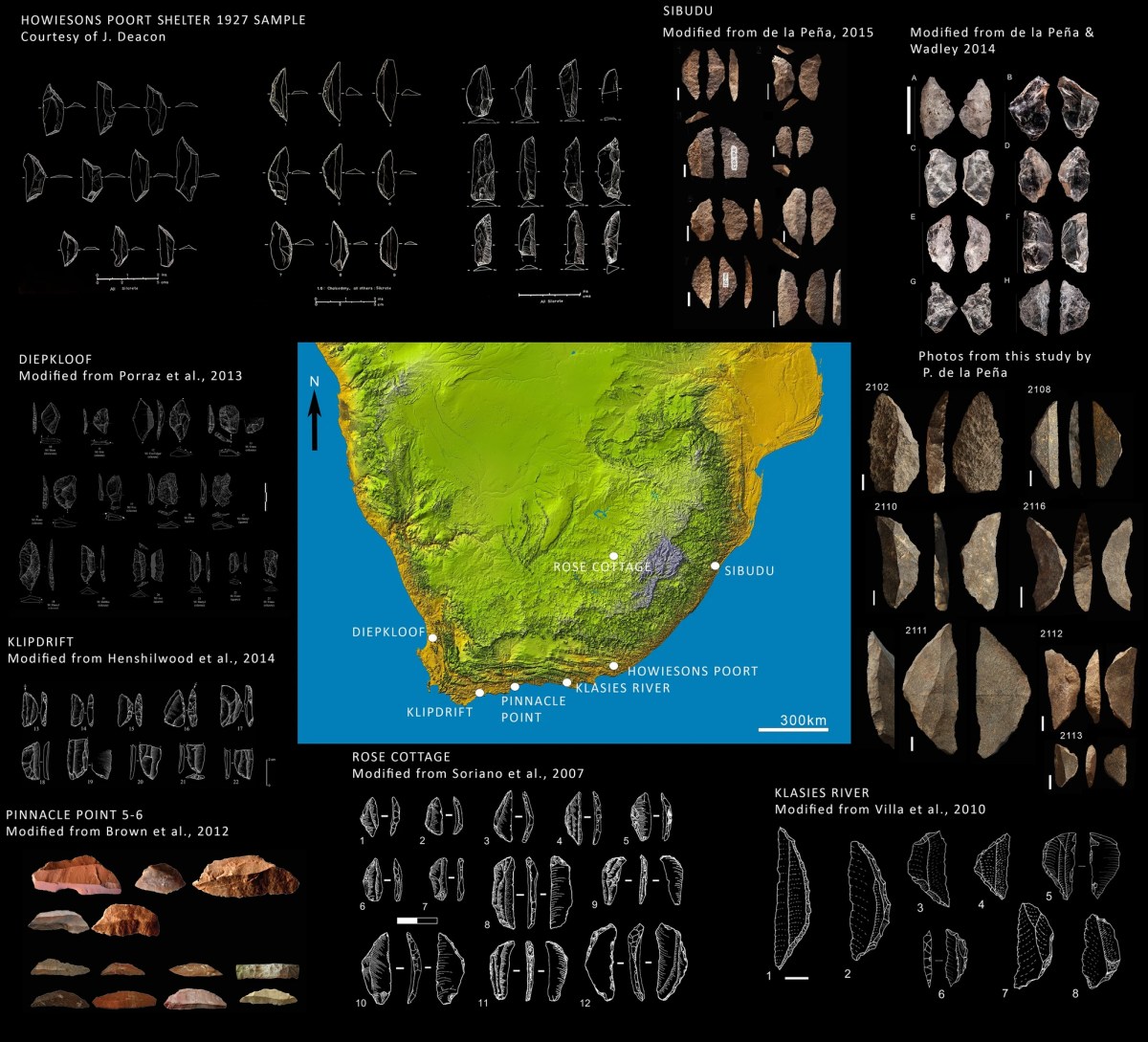

Researchers compared the Swiss Army knife-like tools from seven sites across southern Africa and found that they all had the same shape and used the same template.

Hafted tools were developed independently in other parts of the world across vastly different time periods — and they took on many shapes. But these southern African cultures chose to make their tools look the same, something researchers found “culturally meaningful.”

The team of international scientists analyzing these 65,000-year-old tools was led by University of Sydney archaeologist Amy Way. They concluded that the similarities among the tools across southern Africa indicate that early humans must have been sharing information with each other — they were social networking.

“The really exciting thing about this find is that it gives us evidence that there was long-distance social connection between people, just before the big migration out of Africa, which involved all of our ancestors,” Way said via The Guardian.

Early humans had been migrating out of Africa in smaller numbers before the large exodus approximately 60,000 years ago.

“Why was this exodus so successful where the earlier excursions were not? The main theory is that social networks were stronger then,” Way added.

- Invasive strep: ‘Don’t wait’ to seek care, N.S. woman warns on long road to recovery

- Ontario First Nation declares state of emergency amid skyrocketing benzene levels

- T. Rex an intelligent tool-user and culture-builder? Not so fast, says new U of A research

- Nearly 200 fossil fuel, chemical lobbyists to join plastic treaty talks in Ottawa

“This analysis shows for the first time that these social connections were in place in southern Africa just before the big exodus.”

But just how far did this knowledge-sharing reach? Way says Howiesons Poort blades have been found 1,200 kilometres apart in southern Africa.

“One hundred kilometres takes five days to walk, so it’s probably a whole network of groups that are mostly in contact with the neighbouring group,” she said.

Social networking may have been the reason why homo sapiens were so successful at migrating across the world where other early human species failed, according to Paloma de la Peña, a senior research associate at the University of Cambridge and a lead author in the study.

“The main theory as to why modern humans replaced all the other humans living outside Africa around 60-70,000 years ago is that our ancestors were much better at social networking than the other species, such as Neanderthals, who were possibly smarter and stronger as individuals, but not great at sharing information,” de la Peña said.

Perhaps this research suggests that what makes us people is not intelligence alone, but our capacity to help our fellow humans.

Comments