The Dutch man accused of tormenting B.C. teen Amanda Todd before she took her own life a decade ago pleaded not guilty to all charges in B.C. Supreme Court on Monday.

Aydin Coban was extradited to Canada in 2020 on allegations he harassed and extorted the 15-year-old prior to her death in 2012.

“For me, this is Amanda being able to share her voice. She made this happen. I’m overwhelmed because the day is finally here,” said Todd’s mother, Carol Todd, outside the courtroom on Monday morning.

Coban is charged with extortion, possession of child pornography, communication with a young person to commit a sexual offence and criminal harassment.

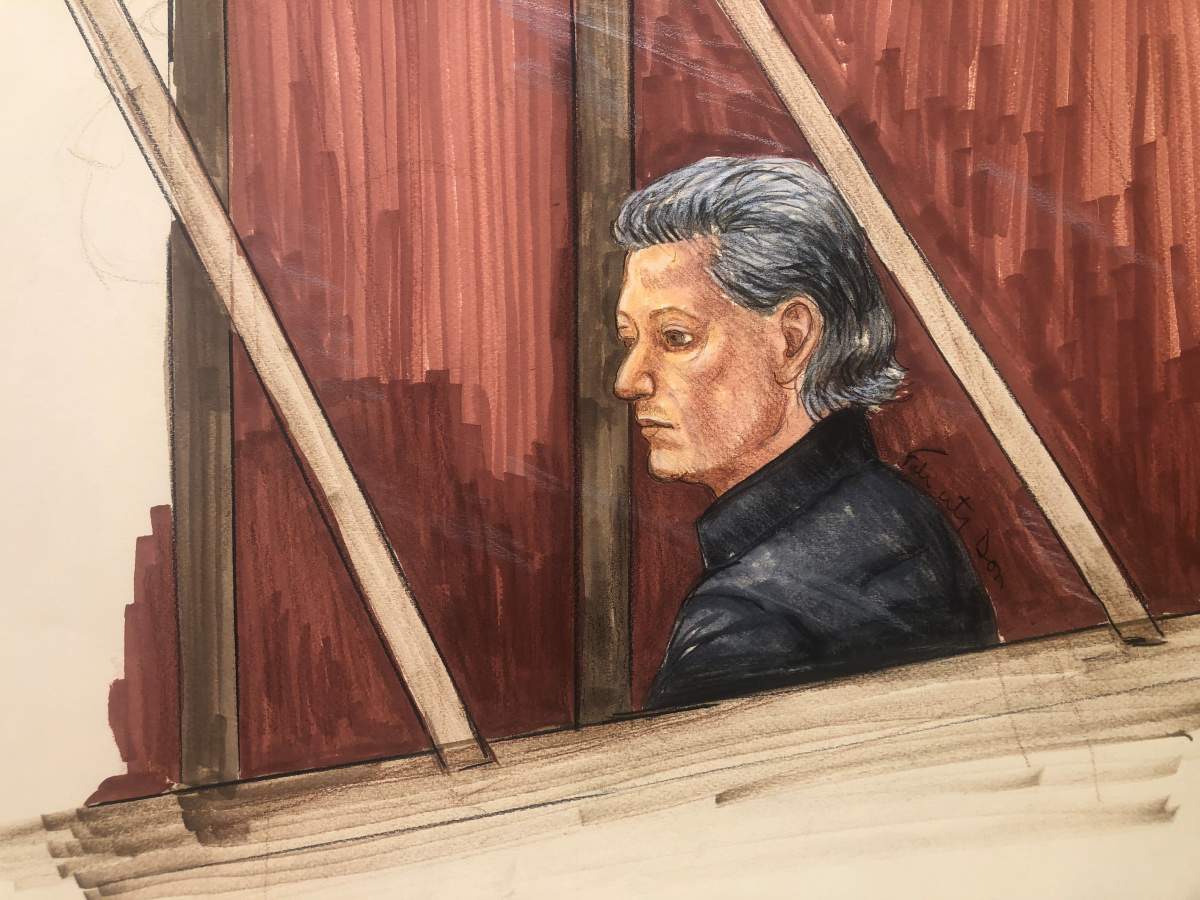

Dressed in a dark collared shirt with his grey hair combed back, he sat silently in the prisoner’s box in the New Westminster courthouse, speaking only to plead not guilty to all counts.

Justice Martha Devlin spent Monday morning laying out court protocols and standards of evidence for the 12-member jury. The trial is scheduled to run 35 days.

Crown alleges ‘sextortion’

In her opening statement, prosecutor Louise Kenworthy laid out the Crown’s theory, telling the jury she would prove Coban used a network of 22 different social media accounts to mount a campaign of harassment and extortion against Todd, grouped into four major “episodes” between 2009 and 2012.

“Amanda was the victim of a persistent campaign of online sextortion,” Kenworthy said.

The Crown alleges that Coban came into possession of explicit media showing Todd baring her breasts and putting her hand in her underwear, which he leveraged in an effort to force her to perform pornographic shows via webcam.

Over the course of the four episodes between November 2009 and December 2011, the Crown alleges Coban used the offending accounts to either pressure Todd by threatening to distribute the intimate material, or to actually send links to the material hosted on websites to scores of people, including friends, family members or her school community.

The Crown presented several examples of the message exchanges, including two in December 2010 from different accounts allegedly both operated by Coban, demanding 10 camera “shows” or he would send video of Todd to friends and family.

Get daily National news

“There is this video of you flashing tits on blogTV,” stated one message to Todd from a Skype message read out in court, to which Todd replied, “What do I have to do so you won’t show anyone?”

“Once a week we just do fun stuff on cam is all,” was the reply.

Later that month, the Crown said Todd received a second threatening message from a different user name.

“Look cam w—, enough nice guy act, you’re going to do as you are told or I am going to f— up your life, got that b—-?” the court heard.

Kenworthy told the jury the Crown would prove both that the 22 accounts, along with other “alternate” accounts used to befriend or collect information from Todd, were all operated by the same person, and that the offender was Coban. She said the Crown would present technical analysis of Facebook login data, common contact information used between accounts, and the content and timing of messages to prove the connection.

“We say that it may become clear to you, when you review certain messages together, that they were authored by the same person,” she said. “We expect you will see that sometimes these users refer back to earlier events or earlier messages that were sent by different users.”

The Crown intends to call numerous witnesses over the course of the trial, including Todd’s mother Carol and father Norm, one of her friends, and one of her teachers.

Numerous Canadian police officers are scheduled to testify, including experts in technology and forensic computing.

The Crown said it will also call several Dutch witnesses, including police who searched the holiday bungalow where Coban lived when he was arrested in 2014, and technology experts who examined computers and hard drives seized at the time.

Todd’s mother takes the stand

For the first time, Todd’s mother Carol came face to face with the man accused in her daughter’s case, taking the stand as Crown’s first witness.

Carol described her daughter as a young woman with an interest in art, singing and social media who had taught herself at a young age to record herself and post it online. Like many kids her age, Carol said her daughter wanted to be the next Justin Bieber to be discovered through YouTube.

She described how her heart “skipped a beat” when she received a disturbing Facebook message from an unknown person a few days before Christmas in 2010.

“It was a link to a video. It was her topless. Shirtless. Did I click on the link to further watch any part of the video? No,” she said.

“I understood what we were seeing — what had been done — was child pornography.”

That same night, the RCMP became involved, Carol testified, arriving at her house to perform a welfare check as a result of a report of something involving her daughter that had been posted online. She told the court she gave the officer a printout and screenshot of the message and link she’d received.

After Christmas, she said she met with Mounties, her daughter and her ex-husband to discuss the issue.

“(Amanda) was quiet, she was a little — a lot — uncommunicative. She appeared to have, sort of, issues with sharing what it was that we all saw,” she said.

“It appeared that her behaviours were that of belligerence, but in talking with Amanda later, it was more about shame, guilt, and afraid of getting in trouble.”

Early the next year, Amanda transferred to another school near her father’s home, where she was living, amid bullying and cyberbullying in the fallout of the explicit video that had been shared in December.

Carol told the court her daughter’s mental health began declining, and outlined two other instances in which her daughter approached her after receiving upsetting messages in May and October of 2011.

“She was scared, she was frightened. It created high anxiety,” she said.

“With Amanda, when she got anxious, she just escalated. It just escalated. It’s hard to describe. She was all over the place. But she wanted something done about it.”

Speaking outside court, Coban’s lawyer, Joseph Saulnier, said the Crown’s case is “probably not as strong as people expect.”

“There’s no doubt that Amanda Todd was the victim of a lot of crimes. This case is about who is behind that. There’s been a lot of publicity about this for 10 years. There’s a lot of emotion wrapped up in these charges,” he said.

“This case is about whether the Crown can prove who is behind the messages that were sent to Amanda Todd … Crown is going to present a very complicated, technical case and my hope is members of the public who follow this case, who read it online, who watch it on your newscasts, can keep an open mind … it’s a case like this where the presumption of innocence is so important.”

Not long before Todd’s death, she posted a video to YouTube chronicling her ordeal, which gained worldwide attention and became a rallying cry against cyberbullying. In the video, Todd silently held up a series of flashcards describing the torment she endured.

The teen described how someone in an online chatroom asked her to expose her breasts, and how she later received messages from a man threatening to release intimate photos of her if she didn’t “put on a show” for him.

In January, a B.C. Supreme Court judge lifted a ban on reporting Todd’s name following an application from Todd’s mother and multiple media organizations. Under Canadian law, the identity of any victim of child pornography is automatically protected.

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs help, resources are available. In case of an emergency, please call 911 for immediate help.

For a directory of support services in your area, visit the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention.

Learn more about how to help someone in crisis here.

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.