Signs that the Canadian housing market might be cooling are coming too late for many prospective homebuyers, as their ability to save for a home is dampened by inflation and rising interest rates limit their ability to catch up to the high home prices that marked the COVID-19 pandemic.

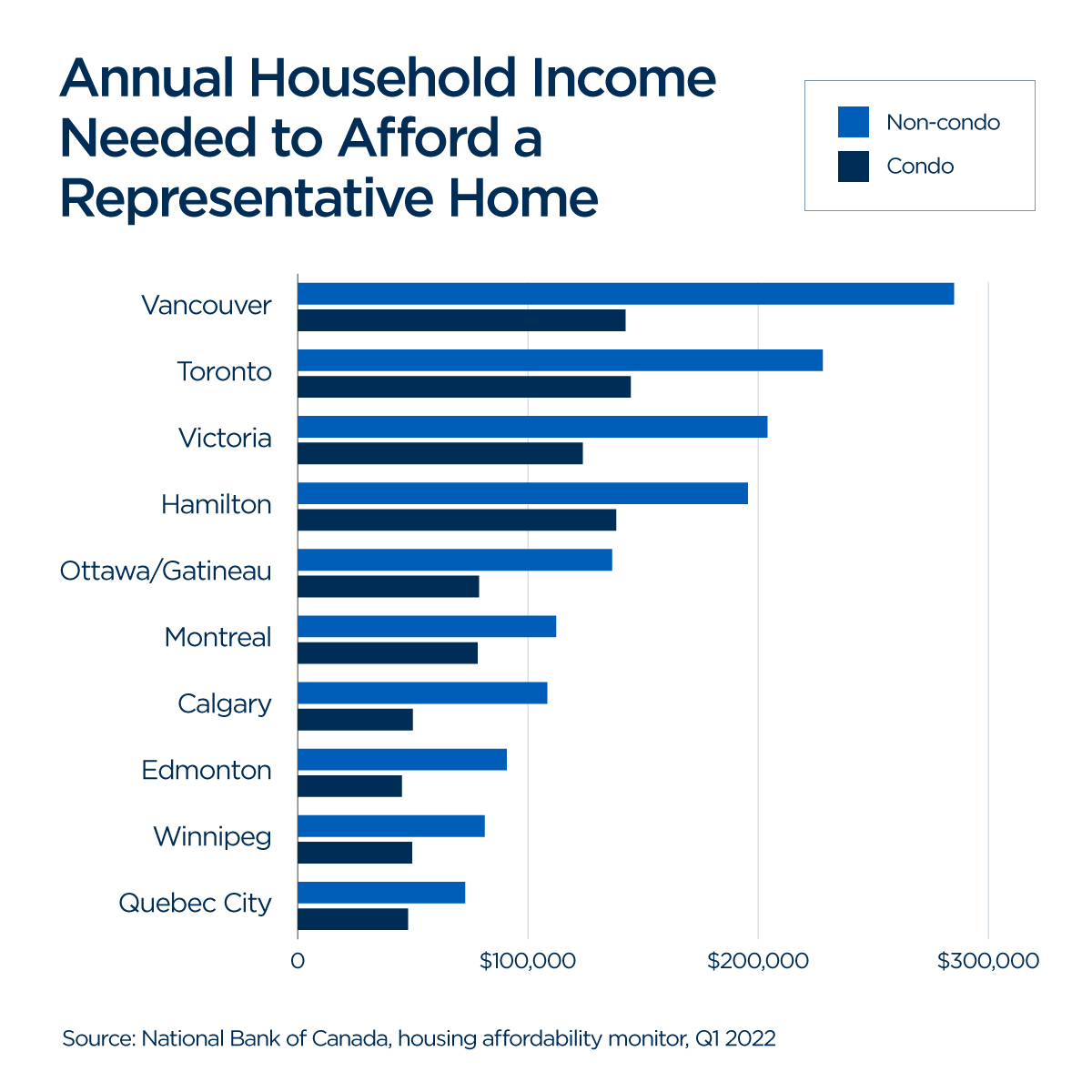

The first quarter of 2022 saw the worst decline in housing affordability nationwide in 27 years, according to a report released Wednesday from National Bank of Canada, with rising mortgage rates pegged as a key factor sidelining would-be buyers.

For Global News’ Sticker Shock series helping Canadians navigate rampant inflation, we spoke to experts and homebuyers exasperated by the eroding housing affordability in the country and broke down how some might be able to make the purchase work.

Shelter, or housing-related costs, was one of the biggest factors driving up the annual rate of inflation to a decades-high 6.8 per cent last month, according to Statistics Canada.

Though some markets such as Toronto saw prices ease month-to-month in April, prices in the GTA were still up more than 15 per cent year-over-year.

Tembeka Pratt, a 30-year-old management consultant looking to buy a home with her partner in the city, says it’s “heartbreaking” to see their dream of owning a home so far out of reach.

“I really don’t know how people in my generation or younger are going to be able to afford something just to get into the market,” she tells Global News.

Home prices out of reach even with six-figure salaries

Pratt tells Global News that she and her partner have been saving up to buy a home for the past two years, something she’s dreamed of for more than a decade.

She put a prudent plan in place over the pandemic: she worked towards a higher-paying job that now earns her a roughly $100,000 salary, well above the average $51,500 annual income the typical Toronto resident their age took home in 2020, per the latest StatCan data.

Together with her partner, the two have a combined income of roughly $200,000.

But National Bank’s affordability monitor shows the annual income needed to afford the median or “representative” non-condo home in Toronto rose to $228,100 in the first quarter of the year.

Pratt says she’s been disheartened to see how little her hard work to bring in a six-figure salary can actually get the couple in Toronto’s hot market.

Get weekly money news

“You would think that that would open so many doors for you, when in reality it’s just not possible,” she says.

The couple is ready to adjust expectations and are looking at townhome properties in the $700,000-to-$800,000 range around the outer limits of the GTA, but there, too, prices are high.

The Toronto Regional Real Estate Board (TRREB) said earlier this month that townhome prices in the so-called 905, outside the city core, hit an average of $997,416 in April.

The inability for younger Canadians to break into the market is a familiar story to Paul Kershaw, professor at the University of British Columbia and founder of Generation Squeeze, which looks at eroding housing affordability across the country.

Someone buying a home in the 1970s needed only five years of full-time work under their belt to afford a home in Canada, he says, while that figure has risen to 17 years of work today. It takes 22-27 years in markets such as Ontario and B.C.

“The amount of work required today to try to break into home ownership has increased so dramatically and in such a soul-crushing way for a younger demographic or a newcomer of any age,” he says.

What goes into buying a home?

Leah Zlatkin, a mortgage broker and expert with lowestrates.ca, says the salary band and price range Pratt and her partner have in mind are a “great starting point” if they manage to find a home that fits their needs.

She says that an individual or couple can typically qualify for mortgages equal to four or five times their income, which could put Pratt and her partner’s affordable range between $800,000 and $1,000,000, depending on their liabilities and whether they take on a fixed or variable-rate mortgage.

Saving for the down payment can be the tricky part in today’s market, however.

A minimum down-payment is equal to five per cent of the home’s purchase price for the first $500,000, 10 per cent of the next $499,999, and rises to 20 per cent above a million dollars.

A sample home at $750,000 would have a minimum down payment of 6.67 per cent, or roughly $50,000.

Hitting the 20-per cent bar on a down payment can also help a buyer avoid paying the mortgage insurance premiums from the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), which are typically tacked onto the monthly cost of the mortgage.

“So you won’t feel it upfront, but you will feel it across the duration of your mortgage,” Zlatkin says.

The decision of whether to try and save to hit the 20-per cent mark or get in with the minimum upfront payment and higher monthly fees comes down to how aggressively you can save, she notes.

The longer you take to save up for a down payment, the more home prices can escalate, raising the overall amount you have to put down.

“It’s like you’re constantly chasing the car that’s slowly rolling downhill. You have to really be able to save that money aggressively in order to catch up to that car,” Zlatkin says.

The down payment and monthly mortgage costs aren’t the only things you need to factor into a purchase, however.

Land-transfer taxes at a cost of $11,445 are paid at both the municipal and provincial levels in Toronto, for example, though rebates are available for first-time buyers in each case.

There are legal fees and title insurance that come with closing a purchase you’ll have to account for, as well as annual property taxes — something most buyers coming from renting have not had to factor into their budgets previously.

“So you want to be really cautious and you want to do your research to understand what those upfront costs might be for somebody who’s looking to buy that first home,” Zlatkin says.

Housing is an ‘intergenerational injustice’

Kershaw says that “housing inflation” is tolerated differently than, say, inflation on the price of gasoline because Canadian homeowners are the ones who generate wealth when real estate prices rise, as opposed to a faceless corporation.

While the Baby Boomer generation has been happy to see their homes rise in value — and even lend some of that equity to their kids to break into the same market — Kershaw says we need a societal shift to show the impact on our younger demographics when we expect home prices to only go up.

“We’ve wanted housing to be this great grower of our wealth, and we need to stop if we think housing should be delivering affordability, because you can’t have it be both,” he says.

Kershaw says he was heartened to hear Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland recently refer to the gap in housing affordability as an “intergenerational injustice,” and hopes it’s the start of a wider policy discussion that could see an end to unchecked growth in the housing market that leaves the youngest Canadians sidelined.

Pratt acknowledges that this understanding of what a home represents for an adult’s financial stability is part of what attracts her to the ideal of homeownership.

“It’s something that will outlive you and can create generational wealth,” she says.

“My parents own their home and pretty much everyone around me owns a home. So it was almost like a given that that’s the next step as you get older.”

Pratt and her partner are willing to be patient, she says, in an effort to avoid jumping at a home and ending up “house poor.” The couple, who’s also saving for a wedding this summer, hopes to get into the market in the next two-to-five years.

“We’re just going to go at our own pace,” she says. “We will own at some point, but we’re not going to deplenish our savings just to get into the market.”

— with files from Global News’s Anne Gaviola

Comments