A fundraising effort has been launched to help save and restore London’s historic fugitive slave chapel and relocate it to Fanshawe Pioneer Village (FPV) from its current home in the city’s SoHo neighbourhood.

Officials with FPV announced the fundraising campaign on Tuesday, the first day of Black History Month, stating that the building’s condition was at risk of further deterioration, and that if action didn’t come soon, “a key piece of the London area’s Black History could be lost.”

The campaign has set a $300,000 fundraising goal for the project, which is being carried out with the support of local community groups, including Black Lives Matter London, the London Black History Coordinating Committee, The Chapel Committee, and the London chapter of the Congress of Black Women of Canada.

“Our board wants to ensure that this project is a success when the building is moved here, and so we want to make sure that we’ve got the funds raised in support of that,” said Dawn Miskelly, executive director of FPV, in an interview Tuesday.

“Ideally, we would love to be able to have the building moved here with its exterior building envelope sealed before next winter. We’re hoping that we can, with the funding coming in place, be able to to make this happen within a little bit longer than a year.”

More than $50,000 has been raised already through The Chapel Project via the London Community Foundation, Miskelly said, and there are plans to apply for matching funds programs, such as the federal government’s Canada Cultural Spaces Fund, and to issue appeals for individual, corporate and municipal contributions.

“We’ll be working with a heritage architect. Right now, our board has commissioned that we can hire him to do the design-development phase, which gives us the very basic drawings for the building,” Miskelly said, adding officials hoped to restore it to how it looked when it was first constructed in the mid-1800s.

“There’s a lot of research that’s happened in the past on this building to give us some insight into how it may be finished once it’s restored here.”

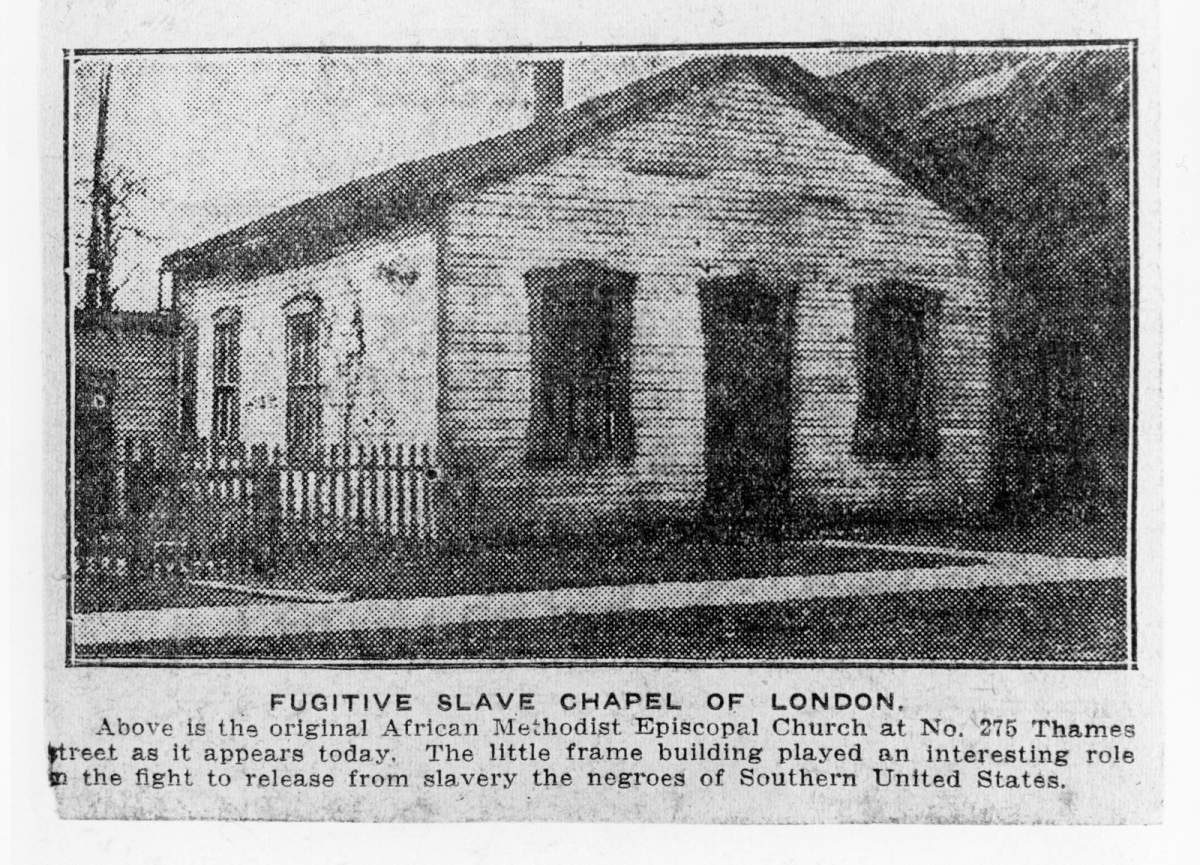

Originally the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the chapel was erected along Thames Street in 1848, and served as a sanctuary for African Americans who had escaped slavery in the U.S. through the Underground Railroad and who had built homes and resided in what is now London’s SoHo neighbourhood.

“Chapel houses of worship were more than houses of worship to the Black community. They were kind of centres of the community … they were meeting places,” said Carl Cadogan, chair of the London Black History Coordinating Committee, one of the groups involved in the project.

Get daily National news

“I think it was important for the community as they were trying to establish themselves in London and southwestern Ontario … the first thing they would build is something like a church, because they serve many purposes.”

Land speculation brought on by the construction of the Great Western Railway in the 1850s brought wealth to the area, making it the richest Black community in Canada, according to a London Free Press report.

The chapel, located at 275 Thames St., later became the British Methodist Episcopal Church in 1856, according to the London Public Library, which notes that abolitionist John Brown is believed to have spoken at the church in 1858, a year before his ill-fated raid on the Harpers Ferry Armory in Virginia in a bid to initiate a slave rebellion.

In 1869, the Thames Street church was replaced by a new church on Grey Street, according to the library. A private residence for years, the former chapel remained and was spared demolition in 2013 following calls from the community. The following year, it was relocated to Grey Street where it has stood since, weathering the elements.

The British Methodist Episcopal Church (BMEC) of Canada, which owns the chapel, had initially planned to restore and turn the historic structure into a heritage and research centre, however the COVID-19 pandemic stalled the plans, according to a Free Press report from early last year.

Last August, it was unveiled that BMEC and the London and Middlesex Heritage Museum, the non-profit which owns and operates Fanshawe Pioneer Village, had entered into talks to gift the chapel over so it could be relocated to the village, preserved and used to educate.

“There are still families in London who’ve been here for hundreds of years,” Cadogan said.

“We want to ensure that the community, not just the Black community, but the community at large, understands the real role that London played during this very important period in the lives of escaped Africans who came to seek freedom in Canada.”

Both Cadogan and Miskelly noted that when the chapel is finally moved, it will share a different narrative about the region’s past than what has been seen previously at the village.

“It adds another voice to the story that we tell at Fanshawe Pioneer Village,” Miskelly said. “It highlights that there were Black people in our community before London was even incorporated as a city. It’s a very important story to share, and we want to make sure that it’s heard.”

Cadogan adds that part of the plan will be to develop an educational program around the chapel to provide a more integrated learning experience so, “It’s not just a building sitting there.”

“We have a committee that’s trying to raise money now, but I think we’ve also had a discussion about a committee that will look at what the programming would look like as well,” he said.

“We’re excited about the possibility that this will bring a different look to Fanshawe Pioneer Village. It will add a dimension that was missing, and it will enhance the overall educational aspect of the contributions of the Black community in London, and also help people to get a broader understanding of where it fits in to the history of London.”

Information on how to donate to the campaign can be found on the London Community Foundation’s website.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.