Circuit breaker lockdowns or COVID-Zero?

To mix COVID-19 vaccines or not to mix vaccines?

Two vaccine doses or three or four?

Self-isolate for five days or 10? How about 14?

Public health guidance surrounding COVID-19 has been constantly shifting — a regular process as science evolves and scientists learn more about the virus.

But no matter how closely people follow the scientific process, it appears messaging from health officials has resonated differently around the world.

Remember when many were left confused as the CDC revoked, then reinstated, mask mandates for fully-vaccinated Americans in indoor settings?

How about when the National Advisory on Immunization (NACI) appeared to say that mRNA vaccines were “preferred”, seemingly opposing the scientific consensus that the best vaccine is the one offered to you first?

Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table doesn’t think there’s much division as some play it out to be.

“We’re really on the same page about the ways to interrupt transmission,” Robert Steiner, director of communications for the table, told Global over Zoom.

“We’re not fighting much anymore about whether we need to put a pause on big hockey games or put a pause on restaurants … We’re really not fighting about vaccines. It’s incredible when you compare us to all sorts of other countries in the world, not just the U.S. ”

Steiner says the messaging from different provinces has been largely consistent, and that the public’s compliance to guidance is a tell-tale sign of success.

“The fact that the public is letting officials change the guidance is a very good thing,” Steiner said.

Not everyone shares the same view, though.

“I’d say the past two years, the messaging has been really inconsistent,” said Jessica Mudry, director of the Healthcare User Experience Lab at Ryerson University.

Mudry says there were several “lost opportunities” for public health officials to resonate with Canadians — starting with teaching them the basics of viral transmission and mutation.

“We did not ever — as a public health message — explain to people what the virus is, what it looks like, how it acts in the body.”

Because many may not understand that viral mutations are common — and that vaccines need to be updated to keep up — Mudry says the public is scratching their heads at the need for booster shots. She says people don’t see how that Omicron is spreading at an incredible speed, despite 77.9 per cent of eligible Canadians being double-vaxxed.

Get weekly health news

“The public assumed, through no fault of their own, that getting a vaccine will be a free pass from COVID-19. There was a really poor explanation to the public about how a vaccine works,” said Mudry.

But it’s not just about communicating the science, Mudry says. It’s about being able to combine science with human behaviour — to produce a message and take action that resonates both logically and emotionally.

One example, she says, would’ve been to base COVID-19 case modelling on the expectation that people will definitely gather over the holidays, because they are ‘social creatures’ that cannot be in isolation for long.

“Sometimes I wonder if they’ve been consulting at all with social psychologists,” Mudry said.

Steiner says health officials did a great job at following the “precautionary principle” — where decision-makers take swift action with the scientific evidence they have at the given moment to avoid a serious crisis — and then tweak guidance as further evidence becomes available.

He also says this process, the norm in science, was communicated clearly to the public.

“We’re learning in live time. We’re communicating in live time,” Steiner said.

But Mudry says the public was largely blamed for not understanding this scientific process, and was met with threats of lockdown from government officials instead — something she says is “really insulting.”

Amidst it all, misinformation surrounding the virus and vaccines has gone rogue during the pandemic.

During the first few months of the health crisis, nearly all Canadians (96 per cent) who sought COVID-19 information online saw info they suspected was false, misleading or inaccurate. However, only one in five individuals fact-checked the accuracy of what they saw online, according to Stats Canada.

With new data and studies being churned out by the hour, an “infodemic” was born.

This “avalanche of information,” as one science communicator calls it, certainly doesn’t make deciphering what’s real and what’s fake easy.

“What’s really key in a public health crisis is amplifying credible sources, not restating the same info from multiple different sources,” said Samantha Yammine, member of the advisory board at ScienceUpFirst.

Yammine points to numbers from provinces like Ontario that are “very misleading.”

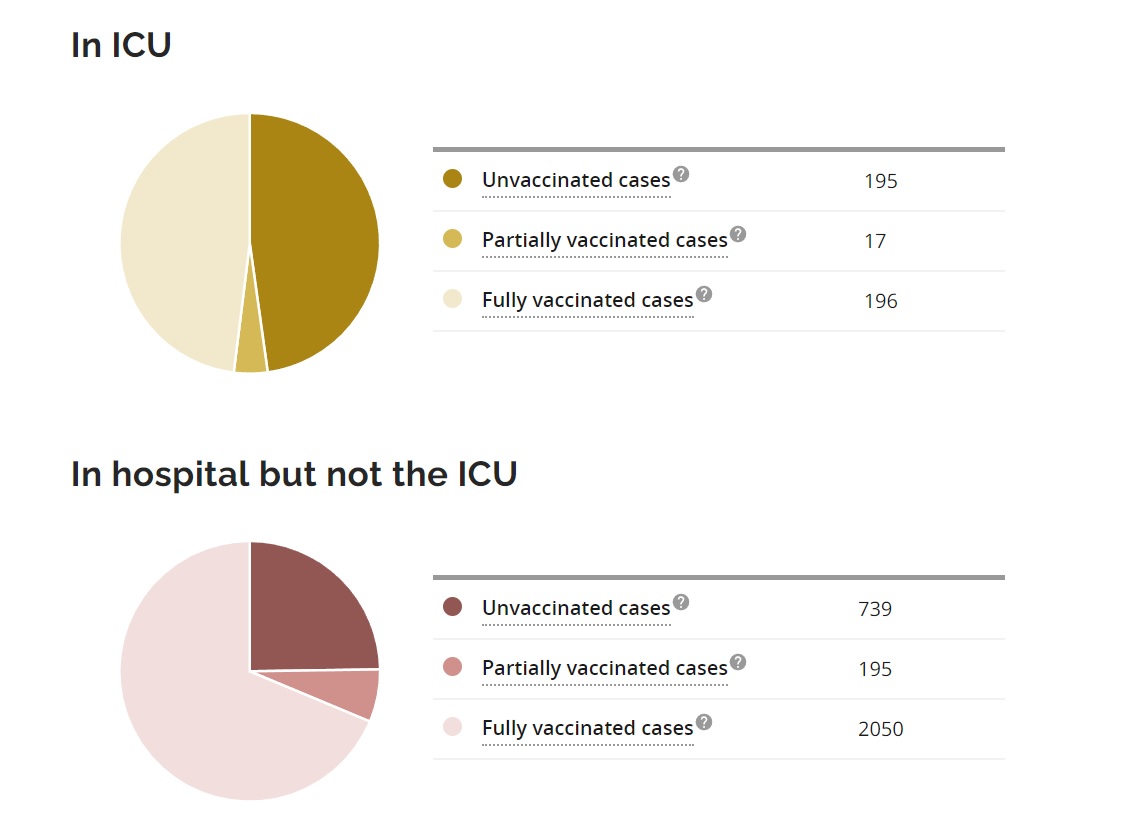

As of Jan. 18, Ontario was reporting COVID-19 hospitalizations based on vaccination status on its online site — but without giving context to the overall number of vaccinated individuals in the province.

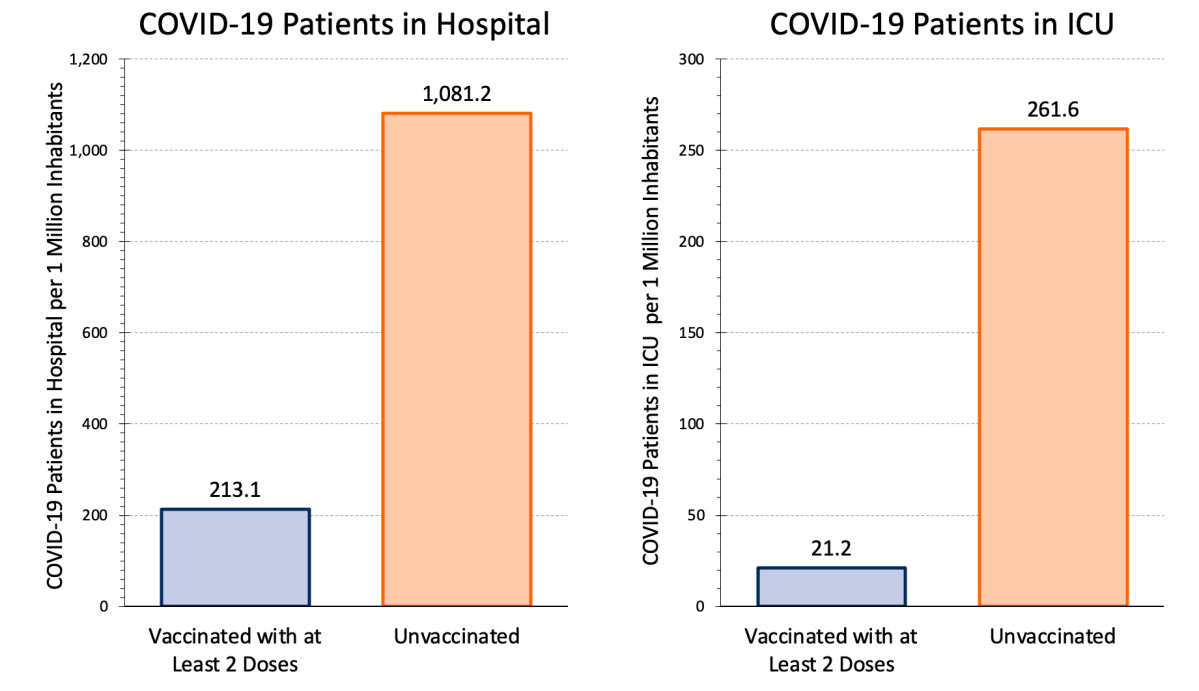

According to the graphs, there were 2,050 fully-vaccinated cases in hospital and 739 unvaccinated cases. This may make it seem that the vaccines are not working, but Yammine says explains that, because vaccinated individuals make up most of the population, it makes sense those with two doses would occupy more beds, even if those unvaccinated are six times more likely to end up in hospital.

“Its a big tactic that disinformers are using,” she said.

Instead, Yammine encourages the public to look at data with a ‘population adjustment’ — such as these stats by the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table.

So what now? As Omicron spreads and pandemic fatigue deepens for many, science communicators say it doesn’t mean there isn’t room for better messaging.

Public health officials have to make it clear that their guidance could be specific to a certain geographic area, according to Yammine. This is why, she says, we could hear different mandates or guidance from officials in eastern provinces than from those in the west. Its also why the U.S. seems slow to enact lockdown measures in comparison to Canada — largely due to its larger hospital capacity.

It’s also important to not blow things out of proportion, such as communicating the number of adverse vaccine events as frequently as the number of vaccinations. According to Yammine, this could create “a bit of a false balance,” giving people the impression that this is a number that is meant to drastically jump up because of how closely it’s being monitored.

The number of adverse events is available to the public.

Engaging with experts in online discussions and on social media is also a great way to combat misinformation, Yammine notes.

And lastly, Yammine says, health officials need to make it clear that treating Omicron like an endemic is not at all possible right now.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.