ST. LOUIS – Pfc. John Eddington was fighting in Europe in World War II when he learned his wife gave birth to a daughter. From the battlefield he penned a letter, sweetly telling the little girl how much he loved her and longed to see her.

But he never made it home, and the letter and his Purple Heart medal ended up in a box thousands of miles away from Peggy Smith, the daughter who was told nearly nothing about him.

Years after a Missouri woman found the box of mementos and underwent an exhaustive search to find the daughter who grew up hesitant to ask about her father because it upset her mother, the letter and medal will be handed over to Smith on Saturday in what figures to be an emotional ceremony in Dayton, Nev., where Smith lives.

It was 14 years ago that Donna Gregory was helping her then-husband clean out his grandparents’ home in Arnold, Mo., a St. Louis suburb. Gregory stumbled upon a cardboard box filled with World War II memorabilia related to Eddington, though no one knows why.

Eddington was from Leadwood, Mo., about 75 miles southwest of St. Louis. Neither Gregory nor Smith know what connection the Arnold couple had to Eddington.

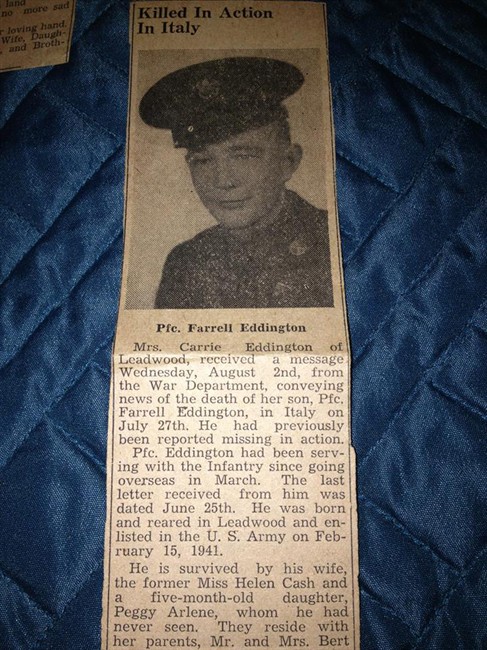

Gregory sorted through several letters, including the War Department’s message to Eddington’s mother about his death in Italy in June 1944, four months after his daughter’s birth. At the bottom of the box she found the Purple Heart, the medal awarded to members of the Armed Forces wounded or killed in action.

Gregory, of St. Louis, then spent the next 14 years in libraries and on the Internet trying to track down the elusive daughter. She called every Eddington in Missouri, trying to find the right Peggy. No one could help.

Earlier this year she enlisted the help of friends and began reaching out on Facebook, leading to a breakthrough — she found Peggy Smith.

Nearly 2,000 miles from St. Louis, Smith said she knew her father died in the war, and knew he earned the Purple Heart. But she didn’t know what happened to it. Smith figured her mother had lost the medal or given it away — until Gregory called.

“It was an unforgettable moment,” Gregory said. Smith said she was “stunned.”

Gregory was touched by the medal, and especially moved by the letter in the box penned by Eddington to his newborn daughter. She declined to quote directly from it, saying Smith should read it first.

“It’s basically a soldier who is pouring out his heart on paper to his daughter,” Gregory, 46, said of the letter. “It’s a letter written so she would know how much her daddy loved her.”

Beyond his death in war, Smith knew little about her father since her heartbroken mother could rarely bring herself to discuss the lost love of her life.

“My mom didn’t tell me much about my dad,” Smith said. “I think she was just distraught. She was so much in love with him. I learned as a young girl not to bring it up because she would just get so upset.”

Smith, 69, grew up in St. Louis and lived there until her mid-20s. By then she was a mother of four young children, but in what she described as an unhealthy marriage. She divorced and moved the kids west for a new life in Nevada.

She spent several years working as an accountant for the state of Nevada, and remarried in 1997. She has since retired from the state job and works at a Wal-Mart store.

Gregory, also an accountant, decided to make the drive to Dayton, near Carson City, to deliver the memorabilia to Smith. She figured it deserved a little more pomp and circumstance.

So Gregory wrote a letter to the Patriot Guard Riders, the volunteer organization perhaps best known for patrolling funerals of soldiers to shield relatives from protesters from Westboro Baptist Church, the Topeka, Kan.-based church whose members believe soldier deaths are God’s retribution for America’s tolerance of homosexuality.

In the letter, Gregory said she thought it would add meaning if veterans presented the medal to Smith.

Before dawn on Tuesday, Gregory, her sister and a friend left St. Louis in an SUV, accompanied by about a dozen motorcyclists with the Nevada unit of the Patriot Guard. Along the route, different groups of riders are taking turns accompanying Gregory.

On Saturday, a parade will begin in Carson City and make the 15-mile trek to Dayton, where Smith will be presented the medal and letter in a ceremony at the high school. Smith’s children and most of her 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren will be there, though she’s a bit embarrassed by all the hoopla.

“I’m not a big shindig person,” Smith said.

Still, she is bracing for the wave of emotions as she reads the letter for the first time and holds that medal in her hands.

“I’ll be crying the whole time,” Smith said.

Gregory knows she’ll be emotional, too.

“I’ve cherished all of this for a very long time,” Gregory said. “I’ve waited for the finale of this journey for over a decade.”

Comments