Santa won’t be the only one taking flight this Christmas Eve, as scientists prepare to launch a telescope that has its sights set on seeing, well, everything in the cosmos.

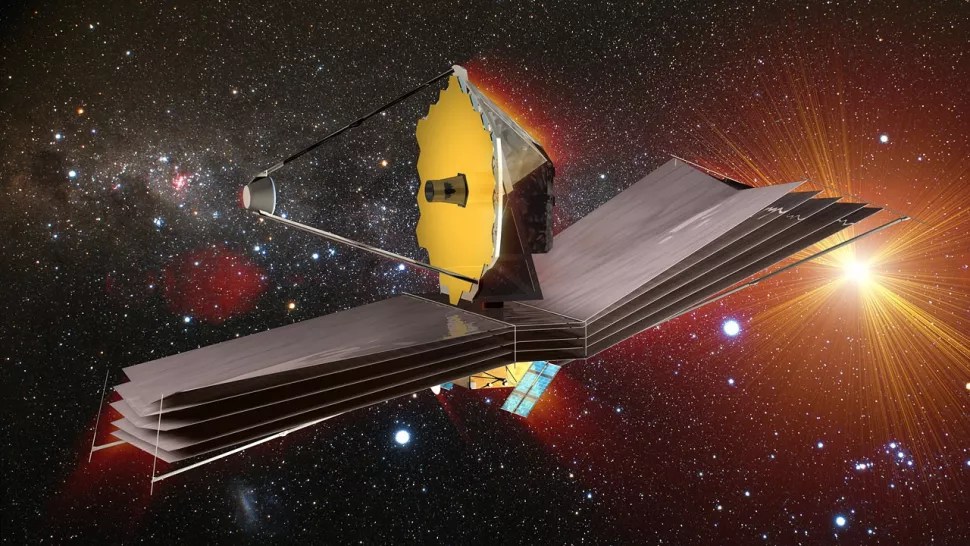

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is set to take flight on Friday, marking the much-anticipated launch of the world’s largest and most expensive telescope to date.

The James Webb is the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which has not only provided stunning images, but has also been vital in providing scientific knowledge about our universe and its origins.

The Webb will be able to peer back in time, possibly to 100 million years after the Big Bang, reports The Atlantic. And not only do scientists think they can look back into galaxies from that time, but they also think they might be able to determine the composition of those galaxies.

“We can actually make detailed measurements of how much of every chemical element is in these distant galaxies,” Steve Finkelstein, an astrophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin who has been working on the project, told The Atlantic.

Finkelstein also said the Webb teams are bracing for some surprises.

“We could make a guess, ‘Okay, I think we’ll do this, I think we’ll see that’ — but we simply don’t know,” Finkelstein said. “We’re looking at the universe in a new way, and we don’t know what we’re going to discover.”

The Canadian Space Agency has contributed to the telescope, providing the Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS) and the Near-InfraRed Imager and Slitless Spectograph, which will be capable of looking for exoplanets, detecting the atmosphere of small, habitable Earth-like planets and giving the ability “to peer inside dust clouds where stars and planetary systems are forming today,” says a NASA fact sheet.

The $10-billion JWST has a much larger primary mirror than Hubble (2.7 times larger in diameter, or about six times larger in area), giving it more light-gathering power and greatly improved sensitivity over the Hubble.

Get daily National news

Rather than operating in the visible light spectrum and ultraviolet, like the Hubble, the JWST is able to look at the infrared slice of the light spectrum, allowing it to see objects previously hidden to the Hubble. It will also be sent much farther from Earth, which means it will have to operate at much colder temperatures.

The Hubble orbits approximately 550 kilometres from Earth, but JWST won’t orbit Earth at all – instead, it will live in space about 1.5 million kilometres from our planet, orbiting a gravitationally stable spot where the pull from the Earth and the sun balance out the observatory’s orbital motion.

And while the JWST has its sights set on the most distant reaches of the universe, Naomi Rowe-Gurney, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, told Al Jazeera that it will also examine the Earth’s solar system.

“There is an entire division dedicated to solar system science, looking at everything from Mars outwards, as well as dwarf planets, comets, asteroids, the rings of all the systems, and all of the moons,” she told Al Jazeera.

To say this technology is exciting would be an understatement – and the space community is having a bit of fun with it. Earlier this month, planetary scientist Peter Gao tweeted: “scicomm: JWST is the biggest telescope to be sent to space it will help find life and tell us how the universe started isn’t it amazing??? / astronomers: my entire career hinges on this bucket of single point failures I’m so nervous I’m crying and throwing up everywhere.”

Astrophysics postdoc Erin May, who studies exoplanet atmospheres, tweeted, “HOW AM I SUPPOSED TO LIVE, LAUGH, LOVE IN THESE CONDITIONS.”

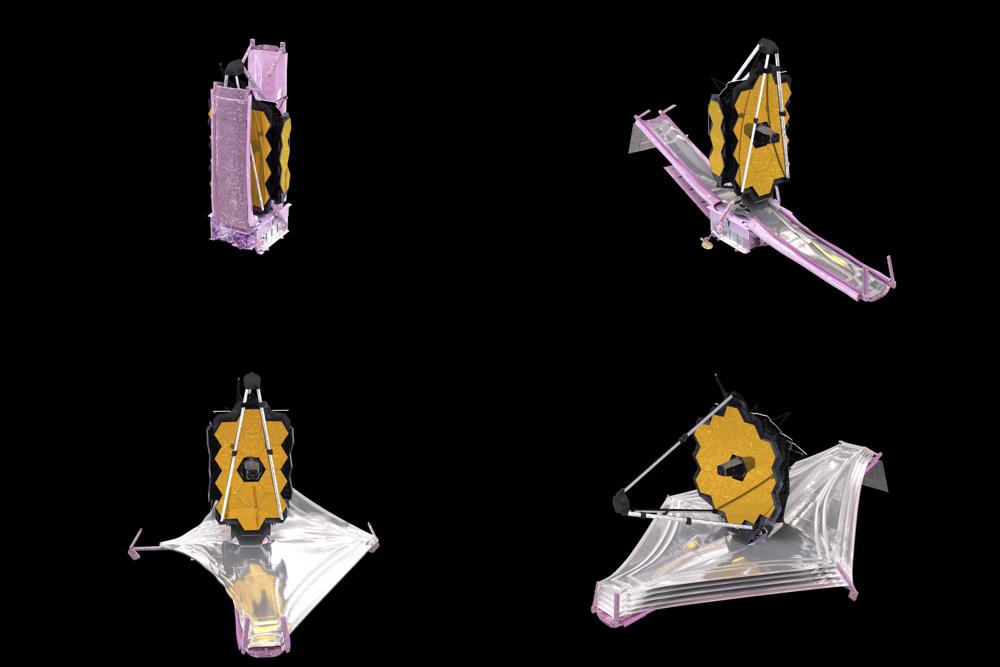

Jokes and memes aside, however, once the JWST launches there will be no second chances. The telescope’s massive sunshield has 107 restraints holding it in place for launch and if one of those restraints doesn’t release correctly, the project will be unsuccessful, reports Slate.

Keith Parrish, observatory manager for the JWST at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, told Slate that “the consequences of just one (of the 107 sunshield restraints) not releasing correctly is fairly dramatic, so I guess the sheer number of those devices (107) that must work correctly can be a little intimidating.”

Working out the kinks of the telescope’s functionality has caused many delays, putting the launch years behind schedule. Because of the distance from Earth, astronauts will not be able to access the Webb for maintenance and fixing, should anything go wrong. NASA has never attempted such a complicated series of steps remotely. Many of the mechanisms have no backup, so the failure of any of 344 such parts could also doom the mission.

So it’s been years and years of testing, and, now, hoping for the best.

“It would be crushing,” Jeyhan Kartaltepe, an astrophysicist at the Rochester Institute of Technology whose team received the biggest chunk of observing time in Webb’s first year, told The Atlantic of the possibility it doesn’t work. “I don’t think I can even express how crushing it would be.”

NASA administrator Bill Nelson said he’s more nervous now than when he launched on space shuttle Columbia in 1986.

“There are over 300 things, any one of which goes wrong, it is not a good day,” Nelson told The Associated Press. “So the whole thing has got to work perfectly.”

The Webb telescope is so big that it had to be folded origami-style to fit into the nose cone of the European Ariane rocket for liftoff from the coast of French Guiana in South America. Its light-collecting mirror is the size of several parking spots and its sunshade the size of a tennis court.

It will take Webb a full month to reach its intended parking spot, four times beyond the moon. From this gravity-balanced, fuel-efficient location, the telescope will keep pace with Earth while orbiting the sun, continuously positioned on Earth’s nightside.

It will take another five months for chilling and checking of Webb’s infrared instruments before it can get to work by the end of June.

— with files from Nicole Mortillaro and The Associated Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.