Staff at Wanuskewin Heritage Park in Saskatchewan have unearthed a major archaeological find, and they did with the unexpected help of some bison that were reintroduced to the park two years ago.

Chief archaeologist Ernie Walker remembers the exact date the discovery happened — Aug. 16, 2020.

Walker and the bison manager were in the paddock located about 800 meters away from the park building and bison jump, which Walker in 1982 named “Newo Asiniak,” which is Cree for “four stones.”

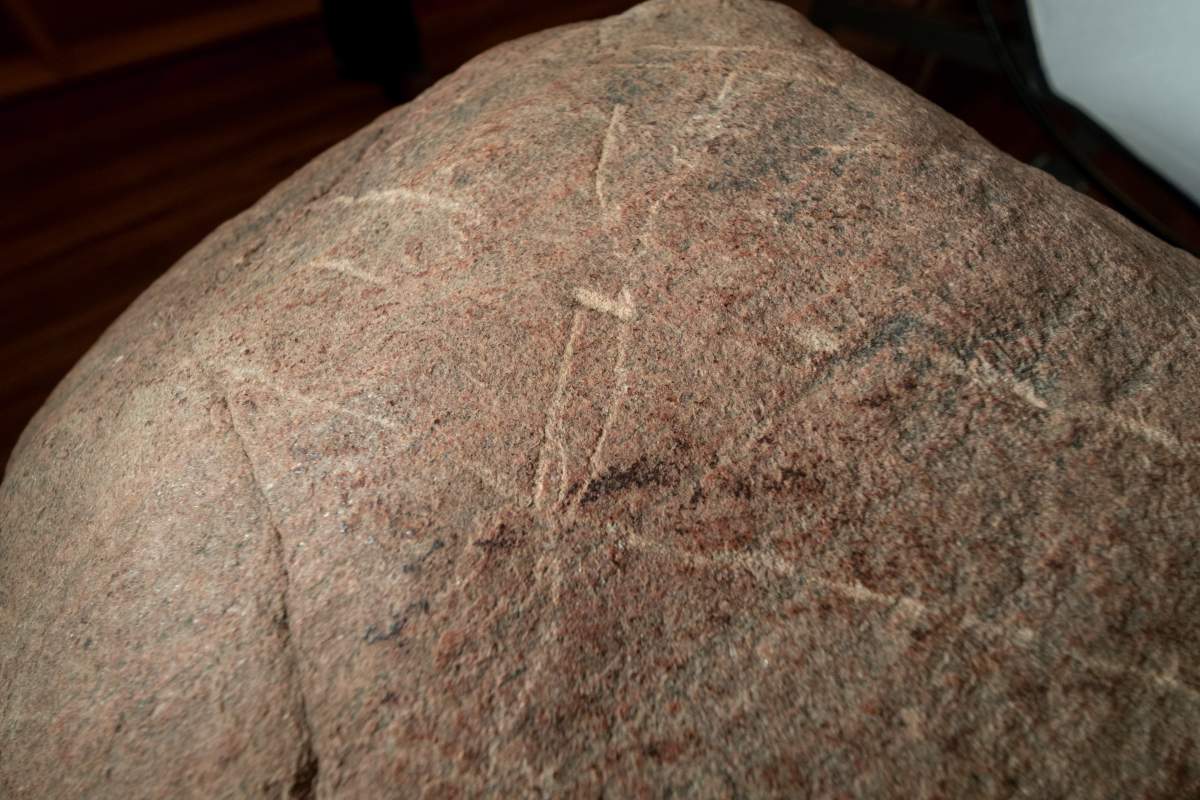

“I just happened to look down at my feet and there was a boulder protruding, partly protruding, through the ground and it had a kind of strange groove over the top of it,” Walker recalled.

He said at the time he thought the groove may have just been damage but ended up brushing away at the soil to expose the rock more.

“It was at that point I realized this is actually what is known as a petroglyph. This is intentionally carved,” Walker said.

“The interesting thing is the bison were the ones that actually partially uncovered it because we’re in their paddock, where they water and they have to pass through this paddock going from one pasture to another. So they do spend quite a bit of time there. They will wallow. They will give themselves dust baths, and they had denuded most of the vegetation.

“They were responsible for showing us these buried boulders,” Walker said. “They’re just very happy to be here.”

Bison were reintroduced to the park in December 2019. It was the first time plains bison were back on their ancestral homeland in over 150 years.

Petroglyphs are carvings, engravings or incisions into a rock, Walker explained.

He said rock art can be found around the world and in the northern plains. There are about nine different styles.

Walker said the four petroglyphs found are carved in the hoofprint tradition, most common in southern Alberta, southern Saskatchewan, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana and Wyoming.

Get daily National news

It’s called hoofprint because instead of engraving a whole bison onto a rock, which would take a lot of work, Indigenous Peoples engraved just the split hooves, Walker said. “So it’s very metaphorical. Those hooves represent a bison.”

From ethnographic information, Walker said there are three things involved with the hoofprint tradition: femaleness, fertility, and renewal.

“And it has to do with bison. It’s about the sacred relationship between females and bison.”

Walker himself was stunned by the discovery. He listed the other artifacts that have been discovered around Wanuskewin: bison jumps, tipi rings, buried campsites, and the most northerly medicine wheel found on the plains.

“What we didn’t have was rock art, and all of a sudden we’re in the rock art business.”

Walker told Wanuskewin CEO Darlene Brander about the discovery right away.

“(Walker) knocked on the door and he knocked in a way that I knew something was up,” Brander said.

“He came in and said that, ‘We found it, we found rock art.’ And my eyes got kind of big,” Brander said. Months before, they had been talking about what Wanuskewin really needed or would like to have. And that conversation led to one thing, she recalled: “Wouldn’t it be great if we had rock art?”

Both Walker and Brander set out to make sure the next steps followed protocol and ceremony, which included consulting elders.

The elders called the rocks “grandfathers.” After some discussion, Brander said the elders granted Wanuskewin permission to move some of them onto the site “so that we could share them with the world.”

She said elders and knowledge keepers were surprised and thoughtful about the discovery.

“There are no manuals that come with the petroglyphs, so really it lends itself to contemplation and thinking about spirituality and the role in culture within the different cultures within the Indigenous communities,” Brander explained. “To see the elders experiencing that was really special.”

The park received a letter from the Saskatchewan Archaeological Society (SAS) attesting that the carvings on the rocks are the result of cultural modification.

“The placement and alignment of the carved images could not be created any other way,” SAS executive director Tomasin Playford wrote.

Brander said this was an extra layer of verification that really supported Walker’s expertise.

She added that if it was any other ordinary person who came across the rock the day Walker did, they may have just walked on by.

She said verification is also really important for the park’s UNESCO World Heritage application. The park was named to the tentative list in 2017 and is still awaiting official designation.

There are 20 World Heritage sites in Canada, none of which are in Saskatchewan.

Brander calls the petroglyphs the final piece that makes Wanuskewin unique in the world.

While excavating to prepare to remove the petroglyph, a stone knife was found adjacent to it about 10 centimetres below the surface.

“This is a stone tool, no question. It had been used and re-sharpened. When I measured the width of the cutting edge of the stone knife, it’s the same width as the grooves on the rock,” Walker said.

Walker said it’s difficult to date rock art, especially petroglyphs, because there isn’t any material to date. He said he typically relies on organic material like charcoal to date an artifact.

However, the hoofprint tradition rock art dates somewhere between 300 and 1,800 years ago.

Walker said he estimates the petroglyphs could be as old as 1,475 years. This is because the biggest bone bed buried in the Newo Asiniak bison jump is 1,475 years old.

Walker says while it’s nice to have found the petroglyphs, he’s more interested in the story behind it.

He says the finding adds to Wanuskewin’s story.

“It’s another dimension now, and this is one that is more related to spiritual kind of things, ceremonial kind of things. Bison jumps are about making a living. Campsites are about habitation and where you live throughout the year.

But when you get around to the medicine wheel and you get around to this, these petroglyph boulders, it’s a different part of society, a different part of life that you don’t see,” Walker said.

He said he believes this find will immensely help the park on its journey for UNESCO World Heritage status.

As for the name Newo Asiniak, Walker can’t recall why he gave that name to the bison jump nearly 40 years ago, but says it’s both interesting and a little strange that now four petroglyphs have been found there.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.