A Quebec man who killed his daughters before taking his own life last July was troubled by an impending divorce and was in psychosis, a coroner’s investigation into their deaths has concluded.

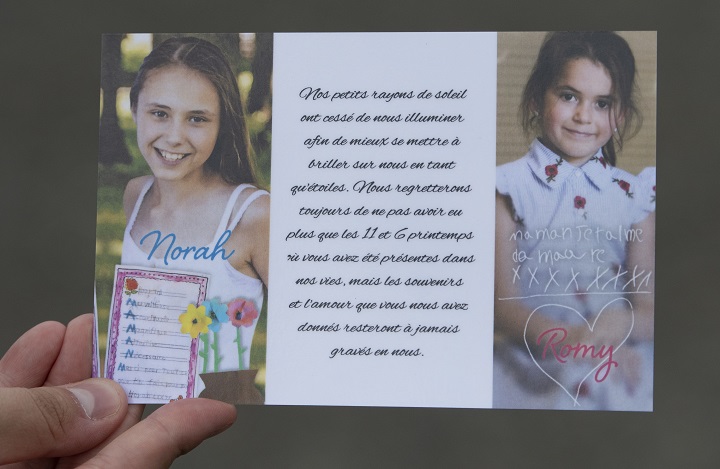

Coroner Sophie Régnière’s report released Thursday sheds new light on the disappearance and killings of young sisters Romy and Norah Carpentier at the hands of their father, Martin Carpentier.

The case gripped the attention of the province, especially in the town of just over 6,000 people where it played out and in the family’s hometown of Levis, across the St. Lawrence River from Quebec City.

Among Régnière’s recommendations are broader criteria for triggering Amber Alerts and the creation of a dedicated police unit to investigate when children’s disappearances are reported in the province.

The coroner found a number of factors hampered the investigation and if things had been handled differently, the girls might have been found more quickly and their deaths prevented.

Romy, 6; Norah, 11; and their father vanished after their car was involved in a serious accident on Highway 20 in St-Apollinaire, Que., southwest of Quebec City, just before 9:30 p.m. on July 8, 2020.

It was not until the next afternoon that authorities took steps to distribute an Amber Alert, issued in cases of child abductions, and even then it was delayed 90 minutes because the initial draft surpassed a 300-character limit for such messages. The alert finally went out at 3 p.m.

Get daily National news

While the coroner agreed an Amber Alert for people missing in a wooded area might not be effective, it could have led to witnesses providing information more quickly. She noted that witnesses who saw the trio going into the forest only came forward after the alert was sent.

The coroner recommended Quebec provincial police conduct an exhaustive overview of their procedures when a child disappears and review their communications strategy.

She found that Martin Carpentier’s actions were possibly triggered by an impending divorce from the mother of the two girls and he was fearful of losing access to them. Romy was Carpentier’s biological daughter but Norah was not and he had adopted her when she was born.

The coroner wrote that Carpentier had been separated from Amelie Lemieux, the girls’ mother, since 2015. But even though he was hoping to remarry, he had not finalized the divorce out of fear of losing access to the children. He was particularly worried about Norah, as Lemieux had re-established contact with the girl’s biological father.

“It was a highly anxiety-provoking situation for him, with a view to losing his children or the meaningful relationship he had with them,” Régnière wrote.

According to his doctor, Carpentier had finally met a lawyer in June 2020 about getting divorced and on July 8, received a document to sign, which may have triggered what happened.

The evening of the crash, Carpentier insisted on taking the girls out for ice cream alone after spending the evening with family. The coroner pointed to several signs suggesting the accident was intentional and the failed attempt at death represented a “point of no return” for Carpentier.

Police initially thought they were simply dealing with someone leaving the scene of an accident, and they were often stymied in getting timely information. When investigators reached out to local hospitals shortly after the accident, staff refused to say whether the three had been admitted, citing confidentiality.

Carpentier’s doctor also cited confidentiality in refusing to provide information to police that could have provided insight into Carpentier’s mental state. The coroner noted the medical code of ethics does allow for an exception in such circumstances and recommended the province’s College of Physicians examine the doctor’s conduct.

In another recommendation, the coroner said the government should send directives ensuring that health information is shared quickly during an emergency situation.

In the hours after the disappearance, Carpentier’s family told authorities he didn’t present a danger to the girls. Only in the early morning the next day did police find out he was depressed and anxious about his divorce. At 6 a.m. on July 9, Carpentier’s fiancée presented investigators with text messages he’d sent the previous evening, before the accident, which read like a final farewell.

“There was no longer any doubt in the minds of the police that the children were in danger,” Régnière wrote. But authorities didn’t immediately send out an alert, which would have reached many Quebecers in the morning.

The coroner ordered a psychological autopsy involving consulting documents, which concluded Carpentier was suffering “an episode of major depression with probable psychotic symptoms and it is in this spirit that he would have ended the lives of his daughters and his own.”

The coroner concluded the girls’ deaths likely occurred on the afternoon of July 9, the same day the Amber Alert was launched. They were killed with blows from a branch. Their bodies were found on July 11 not far from each other, a few kilometres from the crash site.

Martin Carpentier took his own life in the hours after the girls’ killings, but his body was only found on July 20.

Comments