By

Sarah Ritchie ,

Alex Kress &

Brian Hill

Global News

Published April 12, 2021

15 min read

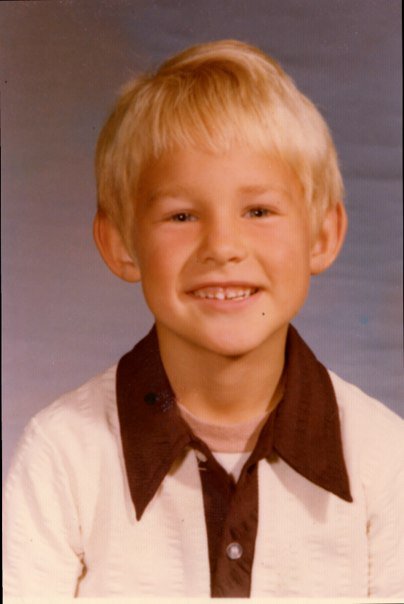

Neil Wortman can vividly describe traumatic experiences from his childhood, decades ago, at the hands of his father. One of the incidents from when he was seven years old lingers in his mind.

“I soiled my shorts. He made me put the soiled shorts on my head, inside out, and told me to start knocking on the doors of neighbours to show them what I had done,” Neil said. “Because I refused to go, he beat me instead.”

Neil, 77, says his father Stanley was a violent man — part of an intergenerational cycle of abuse and violence that culminated in April 2020 with an inexcusable act of mass murder perpetrated by Stanley’s grandson and Neil’s nephew, Gabriel Wortman.

The gunman killed 22 people over 13 hours in Nova Scotia before a chance encounter with two RCMP officers at a service station in Enfield.

The officers noticed a gash on his forehead while filling up their vehicle, and opened fire when they saw him raise a gun he’d just stolen from another police officer after killing her.

The gunman was dead moments later.

Global News has spent months investigating what went wrong, and whether authorities missed early warning signs that could have prevented the tragedy. The investigation included a series of interviews with many people close to the case.

Global News has also reviewed hundreds of pages of court documents and more than a dozen research papers; spoken to psychiatrists, psychologists, sociologists, criminologists, and former and current law enforcement officers to understand what happened and the impact this has had on victims’ families.

Visit Globalnews.ca to read and listen to full episodes ’13 Hours: Inside the Nova Scotia Massacre’

Neil and his brother Glynn Wortman spoke about details of the violent and abusive history throughout multiple generations of their family.

And while no one is making excuses or trying to justify the brutal actions of the gunman, the intergenerational story of violence, revealed through interviews and public records, show a series of warning signs and missed opportunities for intervention that were decades in the making.

“It’s really important not to blame everything on childhood trauma,” said Ardath Whynacht, a sociologist at Mount Allison University in Sackville, N.B. “The overwhelming majority of folks who experience family violence and sexual abuse do not grow up to go on shooting sprees.

“What we’re talking about is untangling the complexity of layers that creates a human capable of engaging in this form of violence. Understanding the reasons doesn’t mean that we’re excusing the violence.”

Scientists have studied the links between childhood maltreatment and violence for decades.

A 2002 study published by the U.S. Department of Justice looked at the arrest records of roughly 900 people with histories of childhood maltreatment.

The study found that abused and neglected children are 4.8 times more likely to be arrested before the age of 18, twice as likely to be arrested as adults, and 3.1 times more likely to be arrested for violent crimes than people who were not abused.

James Densley, a professor of criminal justice at Metropolitan State University, and Jillian Peterson, a psychologist and criminology professor at Hamline University, have studied every public mass shooting in the United States since 1966.

The shootings they study have at least four fatalities that occurred in close geographical proximity. Some of the victims must have been murdered in public spaces.

The pair has identified four commonalities in the lives of mass shooters: opportunity, including access to guns; radicalization; a noticeable crisis point before the shooting; and a history of childhood maltreatment.

After access to guns, childhood abuse and neglect was the most common, occurring in 92 per cent of cases.

“We’re talking about perpetrators whose parents had committed very serious crimes that they themselves witnessed. We’re talking about parental suicide, horrific child abuse, neglect,” Densley said. “Sometimes it goes back two or three generations.”

Wortman appears to share at least three of four commonalities identified in the typical “pathway to violence” for mass shooters — access to guns, a noticeable crisis point, and a history of childhood maltreatment.

While it’s well known that Wortman had access to an arsenal of illegally-obtained guns, and that he reached a crisis point in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, there hasn’t been a lot of public discussion about the details of his family’s violent past.

The gunman’s uncles, Glynn and Neil Wortman, agreed to share some of these details with Global News.

Glynn and Neil said they were abused by their father, Stanley Wortman, and Stanley was also abused by his own father.

They allege the cycle of abuse continued with their brother Paul, who is the gunman’s father.

“There has been a history in the Wortman family from my grandfather, who was brutal to my father, who was brutal to Paul, who was brutal to Gabriel,” Neil said. “Each generation seemed to get worse.”

Glynn is now living with dementia in a care home in Moncton. Neil is his power of attorney and told Global News that Glynn’s condition doesn’t affect his ability to function and that his long-term memory is “excellent.”

Global News has spoken to Glynn six times during the course of this investigation and his description of his memories was consistent from one conversation to the next. Global News has also attempted to verify what he said with other sources.

One of Glynn’s earliest memories is from a trip he and his brother Paul took with their dad when they were young boys.

They were on a ferry that used to run between New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Glynn was about three-and-a-half years old and Paul was around five.

They were standing on the outer deck of the ferry when Stanley picked them up by their ankles and dangled them over the railing, Glynn said.

“I can remember looking down at that water. It was blue-green. I knew it was deep. I couldn’t swim,” he said.

“I was kicking like mad. I don’t know how the asshole ever held on to me. I kept thinking, why isn’t someone coming to help?”

Neil and Glynn also recalled a time when Neil was 12-years-old and Stanley attacked him. He beat him so viciously that their mother Doris ran across the street to get help from a neighbour, who called police.

Stanley had to appear before a judge, Neil said. He was also forced to see a psychiatrist.

“The judge said to him, ‘if you ever come back in front of me again, bring a suitcase,’” Neil said. “My father never hit me again. But he turned at that point from physical torture to mental torture.”

Glynn said their mother was also beaten.

“He used to punch her, knock her down to the floor. I was a little boy,” he said. “I remember in the kitchen he knocked her down in front of Paul and I.”

Neil remembers these beatings, too.

“My mother defended us from a brute, a real tyrant, who would beat us, and she would step in between. So he would beat her instead,” he said.

Glynn and his mother went out drinking one night and came home to find Stanley angry. But after two decades of abuse, Glynn said he couldn’t take it anymore.

He grabbed a knife from the kitchen and went upstairs.

“I thought, you old bastard,” Glynn said. “They were screaming at each other in his bedroom. He had his own bedroom. She wouldn’t sleep with him. He was a pig.

“He got up and started screaming ‘get out of my room!’ And so I ran over to him and stuck the knife in his chest.”

Glynn didn’t kill Stanley, but he wishes he did.

Neil said Glynn was charged with attempted murder, and those charges were later reduced to wounding with intent. Eventually, he said, Glynn was found guilty and sentenced to two years in prison, but released after serving nine months.

The same year Stanley beat Neil so badly that the police were called. Neil’s uncle gave him a gun. He slept with it every night.

“My uncle Arnold gave me, as a gift when I was 12-years-old, a .22-rifle. And I had one shell,” Neil said. “I used to lie in my bed at night and think, ‘I really should shoot that man.’ But I never had the courage.”

Stanley suffered from a heart condition in his final years and died in his bed in the summer of 1977. A young Gabriel Wortman was downstairs playing Monopoly with one of his cousins when Stanley died.

Glynn and Neil stopped by the house on their way to the beach, and the kids told them Stanley hadn’t gotten up that day.

“I went up and looked at his body and thought, thank God, he’s finally gone,” Neil said. “It took a long, long time for the feeling that he left in that house to dissipate. It was there for years. You’d go in there, and you’d get a chill.”

Glynn and Neil said the abuse in their family didn’t end with Stanley.

Search warrant applications prepared by the RCMP included the claim that Gabriel Wortman was “severely abused as a young boy.” Another uncle told police Wortman had a “difficult upbringing.”

Neil and Glynn also had concerns. Glynn said Paul and his wife Evelyn were unfit parents.

Although neither of them ever saw Paul physically abuse his son, they said he was emotionally and psychologically abusive.

Neil also said he witnessed Paul and Evelyn neglecting their son.

“Gabriel was sitting in a chair watching television with his winter clothes on,” Neil said. “When he breathed, you could see the breath, his breath in the air, because Paul refused to turn on the heat.”

Neil and Paul do not have a good relationship and haven’t talked in decades. Much of what Neil knows about his nephew’s early life comes from stories he heard from Glynn, his mother Doris, and Paul.

Glynn told Neil about another incident, when Paul wanted his son to stop carrying around his blankie.

“He made Gabriel sit and watch while he burned his blanket,” Neil said. “This does things to little boys.”

The abuse between father and son allegedly continued into adulthood. Court documents say Wortman was investigated by police for threatening to kill his parents, and that he assaulted Paul on a trip to Cuba.

His common-law partner told police that after the assault, Paul said, “I was a bastard to my wife, I was a bastard to my son, and you need to leave Gabriel.”

Global News tried to reach Paul and Evelyn for an interview by sending letters to their home. A letter was also hand-delivered, but Evelyn refused to take it, saying “I’m not accepting it. Just go away.”

Neither Paul nor Evelyn responded to the letters. Glynn and Neil said they don’t have their contact details.

Global News has talked to family members and friends to gain some insight into what Paul and Evelyn’s home was like when Gabriel Wortman was young. We can tell you what they said about his upbringing, but Paul and Evelyn have not responded to these allegations and there is no way of verifying what we were told.

Paul did speak to the Toronto Sun four days after the killing spree. He told the newspaper that he felt pain and sadness about the shootings and that he was seeing a psychiatrist. He also said he contemplated suicide.

Why some abused and neglected children commit violence and others don’t is unclear.

A 2007 paper by researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, found severe forms of childhood abuse were “endemic” among a group of 37 death row inmates they studied.

All of the prisoners experienced some form of childhood neglect. Roughly 95 per cent were physically abused, 90 per cent were verbally abused and 80 per cent witnessed violence as children.

While the researchers found childhood abuse alone isn’t enough to make someone violent, they said it is “arguably the most crucial single factor” of all risk factors for future aggression.

“Among the many tragic consequences of child abuse, perhaps none is more sobering or more consequential than the increased risk that the abused child will, at some point, turn its pain and suffering against others,” they said.

A study published by researchers at McGill University in 2009 showed childhood abuse and neglect alters the “expression” of DNA. Their work studied the brains of suicide victims after they died.

People with known histories of childhood maltreatment had distinctive “markers” on their DNA when compared to people with no history of abuse.

Their research provided biological evidence of what clinical researchers have observed for decades — abused and neglected children are far more likely to commit violent acts of self-harm, attempt suicide, and die by suicide, than people who were not mistreated.

And that’s important for understanding mass shootings, too. Because many of the killers in The Violence Project’s database were suicidal leading up to or during their attacks.

“They kind of decided it doesn’t matter anymore,” Peterson said. “This is their final act.”

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study was published by U.S. researchers in 1998, and involved more than 17,000 participants, in a range of age groups. The youngest participants in the survey were 19 and nearly half of the respondents were over the age of 60.

They answered a series of questions to calculate the number of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) they were exposed to as kids.

This included physical, sexual and emotional abuse, witnessing violence in the home, living with someone with a mental illness or addiction, and losing a parent to death, divorce or incarceration.

The findings were compared to the participants’ medical histories.

Nearly two-thirds of participants reported at least one adverse childhood experience. Roughly 10 per cent reported three, and 12 per cent reported four or more.

The study found that people with four or more ACEs are 4.6 times more likely to experience long periods of depression, 7.4 times more likely to be alcoholics, 10 times more likely to use intravenous drugs, and 12 times more likely to attempt suicide.

A 2017 paper by British researchers analyzed ACE studies from around the world, including Canada. People with four or more ACEs were found to be 7.5 times more likely to be victims of violence and eight times more likely to perpetrate violence.

The U.S. Centre for Disease Control estimated that eliminating childhood maltreatment could prevent tens of millions of people developing coronary heart disease, obesity and depression.

“It affects virtually all aspects of their functioning,” said Tracy Vaillancourt, a child psychologist and Canada research chair in children’s mental health and violence prevention.

“It affects their relationships with others because this is their first prototype of attachment. And that prototype is destroyed by an adult who should know better and do better.”

Many experts say the existing body of research shows how it is possible to identify people who need help and offer them support in order to prevent violent crimes.

“We can start to think about universal screening for trauma in schools or in doctors offices,” Densley said.

Densley and Peterson also want to see changes to school curriculum so that kids are taught about social and emotional learning, such as how to be empathetic and talking about mental health, alongside math and reading.

They said this will reduce stigma around mental health issues, especially for boys and men, and make it easier to spot a crisis before it’s too late.

“A lot of times people don’t get treatment for many, many years because it’s scary and they don’t know what’s happening,” Peterson said.

Nova Scotia has a specialized domestic violence court that takes a trauma-informed approach when working with abusers and their families.

Offenders must take responsibility for their actions to be eligible, usually by pleading guilty. They’re given a rehabilitation plan, which a judge considers during sentencing.

But Whynacht, the sociologist from Mount Allison University, said there are almost no programs anywhere in Canada designed to help men end the cycle of abuse. And when she’s advocated for them in the past, she’s faced death threats.

“We have this scarcity thinking where we have so little funding for shelters and services for victims of violence that it puts us in a situation where we keep saying there’s not enough slices of the pie,” she said.

But if the goal is to end violence, rather than respond to it, these services are critical, Whynacht said.

“Police and prisons and prosecution do not keep us safer when we’re looking at intimate partner homicide, and when we’re looking at these types of crimes,” she said.

Nothing will ever change what happened in Nova Scotia. But society can learn from the past to prevent future mass shootings.

That’s why Neil shared his family’s story. He believes his nephew was once “a good kid” and he wants people to understand how he “turned out to be an evil mass murderer.”

There have been three mass shootings in the Maritimes in six years. Three people were killed in Moncton in 2014, four people were shot to death in Fredericton in 2018, and 22 people were murdered in Nova Scotia in 2020.

A public inquiry into the Nova Scotia shooting is expected to start hearings in the summer of 2021. A final report is due by November 2022.

The inquiry’s goal is to prevent future tragedies. Experts say more can be done now.

“There’s a sense that mass shootings are inevitable,” Densley said. “What our research shows is that they’re not inevitable, they’re preventable.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs help, resources are available. In case of an emergency, please call 911 for immediate help.

For a directory of support services in your area, visit the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention.

Crisis Services Canada’s toll-free helpline provides 24-7 support at 1-833-456-4566.

Learn more about how to help someone in crisis here.

To subscribe and listen to this and other episodes of 13 Hours: Inside the Nova Scotia Massacre for free, click here.

Comments