By

Sarah Ritchie ,

Alex Kress &

Brian Hill

Global News

Published January 18, 2021

17 min read

A decade before murdering 22 people in one of the deadliest killing sprees in Canadian history, Gabriel Wortman drove from his home in Dartmouth, N.S., to Fredericton, N.B., rented a dumpster, and cleaned out the apartment of a deceased friend.

The dead man, Tom Evans, was a disgraced lawyer who, had he not resigned from the law society and stopped working as a lawyer, would likely have been disbarred following a string of criminal and liquor control convictions in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Click here to listen to episodes of 13 Hours: Inside the Nova Scotia Massacre

The relationship between the two men was profound, even though Evans was 19 years older than Wortman.

This account of their relationship is based on a review of hundreds of pages of police and court documents, property records, corporate filings, and interviews with people who knew them both.

Before his death in November 2009, Evans made Wortman the executor of his estate and left him all his possessions, including a Ruger Mini-14 semi-automatic rifle that police say Wortman used in the killing spree. A mutual friend of the two men, who lives in Maine, was the source of several other weapons owned by the gunman, according to police.

“Tom R. Evans and I have been friends since childhood,” Wortman said in an affidavit submitted to a New Brunswick court in 2010.

Evans addressed Wortman as “my dear friend” in his last will and testament and instructed him to bury his cremated remains at sea in the Old Sow whirlpool in the Bay of Fundy with a dram of Irish whiskey.

He also asked Wortman to publish his obituary, which Evans wrote himself, in the Sunday edition of the New York Times and to host a wake for friends, family and acquaintances with “eats and strong drink” worth up to $500 to be paid for by his estate.

“I give, devise and bequeath the residue of my estate to my dear friend Gabriel Wortman,” reads a notarized copy of Evans’ will.

The will and other documents, including sales receipts for several properties, were submitted by Wortman to a New Brunswick court as part of a lawsuit filed against Evans’ estate following his death.

The documents contain details of the complicated, decades-long business relationship between the two men and explain the source of some of Wortman’s wealth.

People who knew both men have also said the pair travelled to the United States together and smuggled cigarettes, alcohol and maybe other illegal items across the border using a sailboat Evans owned and that Wortman inherited.

Wortman’s uncle Glynn Wortman, who shared an apartment with Evans when the pair first met, said that he knew Evans was a bad influence and that at one point he tried to warn his nephew’s parents.

“I said to his parents, get Gabriel the hell away from Tom Evans. He’ll only get him in trouble,” Glynn said.

On the evening of April 18, 2020, roughly 10 years after Evans died, Wortman embarked upon a 13-hour-long shooting spree that left 22 people dead, multiple homes and vehicles burnt to the ground, and a nation searching for answers.

In the weeks after the shooting spree, police discovered $705,000 in cash buried in the yard of one of the properties Wortman owned in Portapique, some of which he purchased just months after Evans’ death and the sale of two apartment buildings the pair jointly managed in Fredericton.

The Mini-14 rifle was found in a vehicle owned by Gina Goulet, the last person Wortman killed.

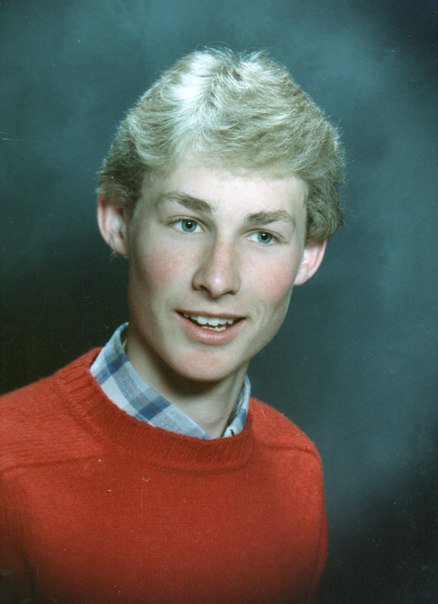

Evans was a well-known Fredericton lawyer during the 1980s.

Lawyers who went up against him in court say he was a character, a menace, devious and “entertaining as hell.”

One lawyer who knew Evans said he remembered him being one of the first people he knew to own a cell phone, back when they were the size of a lunchbox.

A 1983 article in the Fredericton Daily Gleaner described the one-man legal clinic Evans ran out of a storefront on Westmorland Street. A photo in the article shows the clinic had a sign in the window that listed flat-rate fees — $30 for a simple will, $250 for an uncontested divorce.

Evans also practiced criminal law, but his career was short-lived due to his own legal troubles.

In September 1987, Evans was convicted of one count of unlawful use of a firearm without reasonable precaution and given a one-year suspended sentence with one-year probation and a firearms ban, court records show.

According to evidence from the trial, Evans and two British soldiers stationed near Canadian Forces Base Gagetown were caught firing weapons in the direction of a bible camp while operating a 16-foot aluminum boat.

Evans was drunk at the time of the incident and adults at the bible camp had to evacuate 97 children to higher ground because bullets were knocking off tree branches and “whistling by” them, court records show.

Military police who responded to the incident found 197 rounds of spent ammunition and five weapons at the scene of the crime — a 12-gauge shotgun, a skeet shooting rifle, a 22-calibre rifle and two .223-calibre rifles, the same calibre as the Mini-14 Wortman used during the killing spree 33 years later.

Evans was also suspended in 1987 by the law society for a year after being found guilty of four counts of unlawfully supplying liquor to a minor, court records show.

Evans continued to practice law after his suspension.

In 1989, he defended a Colombian cartel member who was part of a group of five accused of orchestrating a prison break. They had come to New Brunswick to free two fellow gangsters who were jailed after crashing a plane filled with cocaine into a snowy field near a remote airstrip just outside Fredericton. Media reports from the time say police estimated the drugs had a street value of $250 million.

Police stopped the five cartel members before they reached the jail. A search of their vehicles found several automatic weapons, including an AK-47 and an Uzi submachine gun, plus nearly 2,000 rounds of ammunition.

Evans’ client pleaded guilty to conspiring to commit the jail break, and was handed the maximum 10-year sentence. Evans complained to reporters that the judge made up his mind about the sentence before the hearing.

Then, in May 1990, Evans was again suspended by the law society after he was charged with sexually assaulting an underage boy and plying him with liquor.

Evans was convicted of this crime and sentenced to three months in jail, but resigned as a lawyer four days before his guilty verdict was handed down. This prevented the law society from conducting its own disciplinary investigation into the charges.

Evans appealed the conviction in 1991 but lost. He never again worked as a lawyer.

After Evans’ conviction, the New Brunswick law society changed its rules so that lawyers who are under investigation for serious crimes or unprofessional conduct cannot avoid being disbarred by resigning before the investigation is complete.

Court records show Evans was pardoned for the 1987 and 1990 criminal convictions, as well as two convictions for breaching the federal Income Tax Act, in 1994. But these pardons were rescinded in 2005.

The Parole Board of Canada, which administers federal pardons, said it is prohibited by law from providing specific details of an individual’s application for a criminal record suspension or the specific reasons why a pardon is rescinded.

A spokesperson for the Parole Board did, however, say a pardon can be ceased if a person is subsequently convicted of a crime or otherwise shown to no longer be a law-abiding citizen.

There is no evidence in the court documents that Evans sexually assaulted Wortman and no one interviewed for this story said the relationship between the two was abusive.

Seven years after Evans was convicted of sexual assault, Wortman purchased the Fredericton apartment building where the incident occurred, according to provincial mortgage and court documents.

Wortman allowed Evans to continue living in the apartment for free in exchange for collecting rents from other tenants, paying the bills and doing maintenance work.

Although Wortman was responsible for the $100,000 mortgage for the property, it was, on paper at least, owned by Northumberland Investments Inc., a company that Evans set up in 1984 with Fredericton real estate broker Sybil Rennie.

But Wortman claimed to have taken over the company in 1996 when he paid Rennie $100 for her shares. This claim was supported by a handwritten receipt he submitted as evidence in a lawsuit filed against Evans’ estate.

Wortman also claimed Evans had no ownership stake in the company, even though he started it and was listed as its president for more than a decade.

When Wortman bought Northumberland Investments, the company owned another apartment building adjacent to the apartment where Evans lived. Property records show Evans and Rennie signed two mortgage agreements for this building, one in 1984 when they bought it and another in 1988, valued at roughly $160,000.

Nothing in the court files indicates that Wortman paid anything for the second apartment building aside from the $100 cash given to Rennie when he took control of Northumberland Investments.

Attempts to locate and contact Rennie were unsuccessful. A realty company she ran in New Brunswick was dissolved in 1998, according to corporate records, and a listed phone number no longer worked. There is a business listing in Florida for a person with the same name, but no contact information is available.

Joe Cartwright was a close friend of Evans and met him in the early 2000s. Cartwright said he had just left foster care, at the age of 15 or 16, and needed a place to stay.

Evans, who was in his 50s at the time, set him up with an apartment in the same Fredericton building where he lived and gave him carpentry work at the properties he managed.

Cartwright said Evans was the best friend he could have asked for and that he helped him out when no one else would. He said Evans paid him well, treated him fairly and was fun to hang out with.

“We had a camp out in Cole’s Island that we’d go out and we’d hunt every year,” he said.

“But it was more of a go out and get drinks, right? So let’s go shoot some things.”

Cartwright said that he met Wortman on several occasions in the years before Evans died in 2009. He said Wortman was a violent and scary man and that he once saw him punch a contractor in the face for walking across his lawn and saw him physically assault his common-law partner.

Despite Wortman’s violent behaviour, he was calm around Evans, Cartwright said. He listened to Evans when he talked and made sure everyone else listened, too.

“Tom was like a father to Gabriel,” Cartwright said. “Gabriel wouldn’t have been Gabriel without Tom.

“He molded him into the professional person that he would become, I think. But he also molded him in other ways.”

After his legal career ended, Evans worked as a handyman, a sort of jack of all trades. His obituary said he was a pilot and an electrician.

In 2005, while doing electrical work on a building in Fredericton, Evans left a 500-watt lamp unattended in the building’s attic. The fire marshal determined it started a fire that caused more than $200,000 in damage to the property.

The property owner’s insurance company then sued Evans, but the case dragged on for years and Evans died before it went to a hearing.

Lawyers for the company continued the lawsuit against Evans’ estate because they believed he, and not Wortman, owned the Fredericton apartment buildings.

But Wortman argued that he owned Northumberland Investments and the buildings outright and that Evans was broke when he died.

In a court filing, Wortman said Evans’ only assets were a lease on a campsite, an old sailboat worth $500, some tools, and “other personal belongings,” which he claimed he took to the dump.

There was also a bank account in Evans’ name with $172.78, Wortman said. He claimed all of this money was owed to the Canada Revenue Agency for unpaid taxes.

“There are no assets of any real value to administer,” Wortman said in an affidavit submitted to the court.

The insurance company also sought a court order preventing Wortman from selling Northumberland Investments, which, owned the Fredericton apartment buildings, and from moving any proceeds if he did sell the buildings out of the province.

But before the judge could decide whether to issue an order, in February 2020, Wortman sold the buildings to a local real estate developer and transferred the money to a bank in Nova Scotia.

After legal fees, repayment of mortgage debt and other expenses, Wortman made $232,201 on the sale, court records show.

The insurance company eventually dropped its claim against Evans’ estate and agreed to pay Wortman $1,500 for legal expenses.

But Cartwright, who said he saw Evans with large quantities of cash on more than one occasion, thinks Wortman lied about the content of Evans’ estate.

“When you can watch a guy go into the bank and draw out $250,000, pretty damn close to a millionaire,” he said.

Evans also had hiding spots built into the walls of his home, Cartwright said.

“He could go up and push a panel on his wall and it’d pop out. And there’d be a secret hiding spot in there,” he said.

This is similar to what police say witnesses told them about Wortman having secret compartments at a property he owned in Portapique, including one near the bar where he kept a military-style rifle.

Cartwright said he doesn’t know how Evans earned the kind of money he had, but he knew he and Wortman smuggled cigarettes and alcohol from the U.S. into Canada using a sailboat Evans owned.

“I have my suspicions,” he said. “But I never seen (sic) anything firsthand.”

Cartwright said he once tried to ask Evans why he was withdrawing hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash from the bank. Evans shut down the conversation immediately, he said, and wouldn’t give him an answer.

“He said ‘those are questions that will get you killed,’” Cartwright said.

It’s not that Cartwright thought Evans would harm him. In fact, he said Evans shielded him. By shutting down conversations like this, Evans kept him at a distance from the darker, possibly illegal, aspects of his life, he said.

“I had to be a little bit sneaky, to find out the little bit of information that I did know,” Cartwright said. “I was the one living that life, right? I needed to know whether I was safe or not.”

In November 2009, three days after they last partied together, Cartwright and another friend began to worry when they hadn’t heard from Evans. They entered his apartment with a key Evans gave Cartwright and found him lying dead on his bed. Cartwright said he believes Evans died of natural causes.

“It devastated me losing him,” he said.

The Fredericton police department, which investigates all sudden deaths, determined there was no cause for suspicion or criminality involved in Evans’ death.

Wortman showed up a few days after Evans died with a dumpster and a couple of other men and cleaned out the apartment, Cartwright said.

“Everything was there,” he said. “I know for a fact that Tom had guns.”

Cartwright couldn’t identify the guns by make or model, but said they were rifles and that Evans kept them in a lockbox in the bathroom.

He also said Evans owned about $100,000 worth of carpentry tools at the time of his death, which he said Evans had promised to him before he died, a sailboat, ATVs, a skidoo and a 1974 Volkswagen Thing.

Police said in search warrant applications that the Mini-14 rifle Wortman used in the attacks belonged to Evans prior to his death. The weapon was given to Wortman by another friend of Evans who built a cabin with him outside Fredericton.

The search warrant applications also show that Wortman obtained several other weapons used in the attacks from a man who police say he met more than 25 years ago through Evans.

A Ruger P89 pistol Wortman used, plus two Glock semi-automatic handguns, were purchased by the friend, who lives in Maine, police said. This man told police the guns were either given to Wortman as a gift or taken from his property without his knowledge, court records show.

This friend from Maine also reportedly told police that Wortman obtained a semi-automatic carbine police say was used in the attacks from a gunshow in the U.S. Police were told that a mutual acquaintance bought the gun thinking it was for another friend, who then gave it to Wortman. The court records describe the purchase as a “dirty” deal, with no paperwork and no background check.

Police say all of these weapons — excluding the Mini-14 rifle — were smuggled into Canada illegally. Wortman did not have a firearms license and was therefore prohibited from owning guns.

The RCMP refused to answer any questions about the relationship between Wortman and Evans.

After Wortman sold the Fredericton apartment buildings he started buying up land in Portapique, where the killing spree began

Deeds and other property records show he bought at least three parcels of land in the area between 2010 and 2014.

This includes the tract of land where he built a “warehouse” to store his collection of police memorabilia, motorcycles, and a mock RCMP cruiser. Police say he used this cruiser to perpetrate the killings and keep “steps ahead” of investigators during the 13-hour manhunt.

Police say the April 2020 killing spree began at a cottage where Wortman and his common-law partner lived in Portapique. Mortgage records show the property was originally purchased by Wortman and his parents in 2002.

The parents eventually gave up their stake in the cottage in 2010. Court records show police were told Wortman threatened to kill his parents that year when his father, Paul Wortman, refused to take his name off the deed.

There was also a 2011 bulletin sent out by Nova Scotia Criminal Intelligence Service that said a police officer from Truro, N.S., was tipped-off by an unnamed source who claimed Wortman wanted to “kill a cop” and had illegal weapons at his cottage. The bulletin said Wortman was investigated in 2010 for threatening to kill his parents. Neither incident resulted in any charges being laid.

The bulletin said Wortman may own several long rifles, “stored in a compartment behind the flue” of his cottage.

Around the same time as the dispute with his parents, Wortman lent his uncle Glynn $165,000 to purchase a home in Portapique that was across the street from his own property, court records show. Wortman was listed as a joint owner.

But when Glynn repaid the loan the following year, Wortman insisted on keeping his own name on the deed.

It wasn’t until the court issued an order allowing Glynn to sell the cottage to Lisa McCully in 2015 that Wortman was forced to give up his claim to the property.

McCully is believed to have been one of the first people killed by Wortman during the shooting spree. She was shot at her home while her two children hid in the basement and called 911.

It’s unclear whether Wortman used any of the money he obtained from his business and personal relationship with Evans to purchase the properties in Portapique or to finance the loan to his uncle.

But Cartwright, who said he did work on Wortman’s cottage not long after he bought the property, said Wortman acted like he was rich and wanted everyone to know it.

When police showed up at his door after the killing spree he said he immediately knew what it was about.

“I was shocked that I knew who he was. Am I shocked that he’s capable of that? No.”

With files from Silas Brown, Brennan Leffler, and Susan Allen

Comments