It was a reunion as unlikely as it was unforgettable — and it was 82 years in the making.

When Betty Grebenschikoff and her family escaped Nazi Germany in the spring of 1939, she left behind dozens of family members who couldn’t get out and were eventually murdered in extermination camps.

She lost cousins, aunts and uncles, and all four grandparents.

“I’ve never counted how many,” she says. “I would say two dozen.”

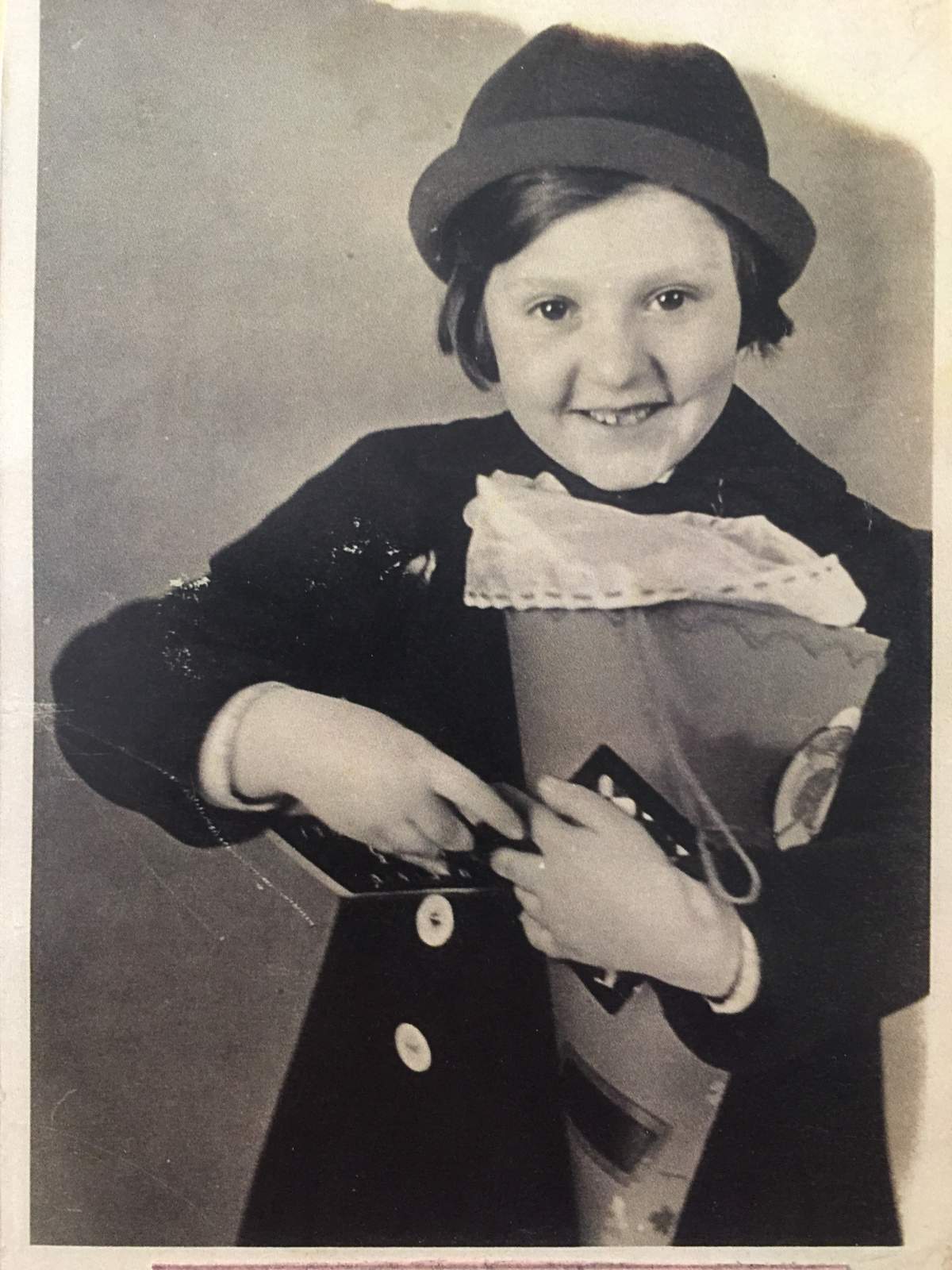

Grebenschikoff was just nine years old and living in Berlin when her family fled. One of the last things she remembers before leaving was saying goodbye to her best friend. She and Anne Marie Wahrenberg did everything together. They were in the same class, went to the same synagogue and played at each other’s homes.

To say goodbye, the girls’ fathers took them to the schoolyard.

“We cried and said we’d write letters and always be friends,” Grebenschikoff says. “But we lost touch. Totally.”

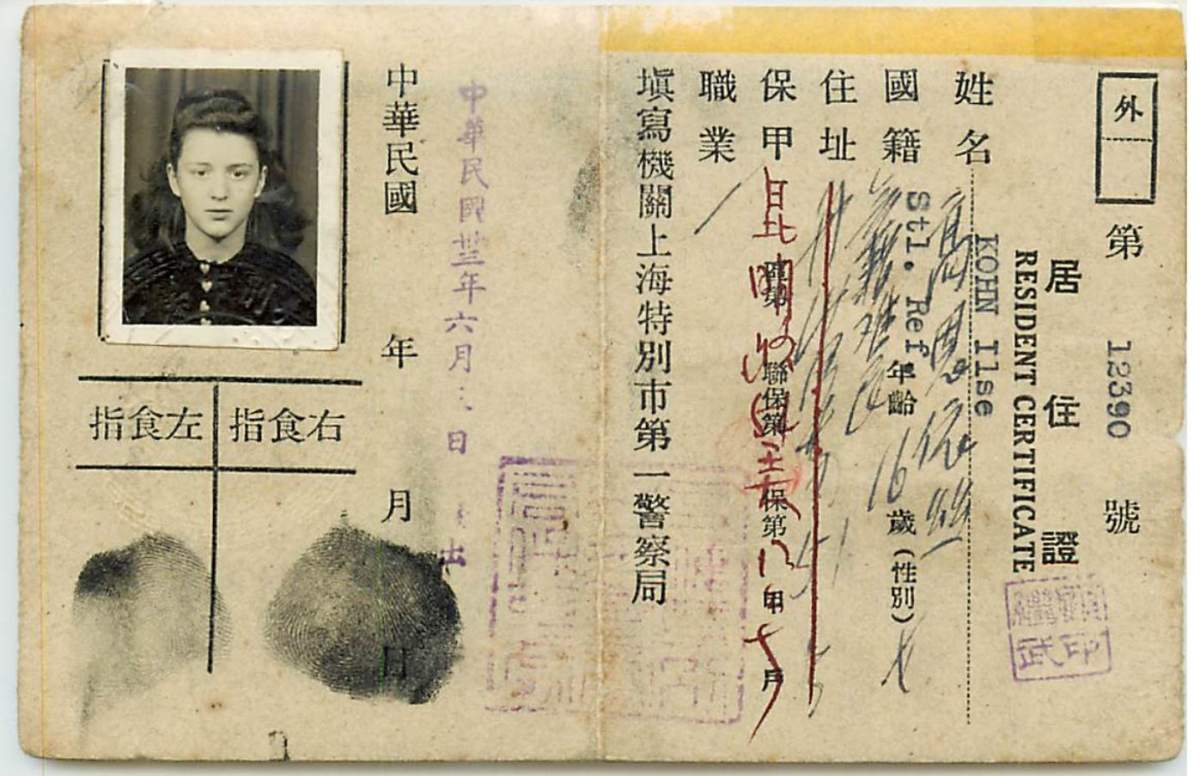

Grebenschikoff and her family would settle in one of the only places in the world accepting Jews without visas, Shanghai, China.

The port city would become home to 20,000 paperless Jews, but it was a difficult life.

When the Second World War broke out, the city was occupied by Japanese forces. After the war, Grebenschikoff was caught up in another of history’s greatest upheavals, the Chinese communist revolution. Her family was forced to find a new home once again.

Grebenschikoff would marry, move to Australia for a year, and eventually settle in Ventnor, N.J. She and her husband would raise five children.

Through it all, she would always wonder about her best friend. When, later in life, Grebenschikoff would start writing and giving speeches about the Holocaust and the Shanghai Jews, she would always try to slide in a story about Wahrenberg.

In 1997, she was interviewed by the USC Shoah Foundation. The organization was founded by Steven Spielberg and has collected 55,000 testimonies about the Holocaust.

Speaking about her life growing up in Berlin, she asked if she could mention her friend.

“Can I mention her here?” she asked. “Her name was Anne Marie Wahrenberg, and I’m always wondering what happened to her. Maybe she’s somewhere and can see this.”

For years, Grebenschikoff would search databases for any sign of Wahrenberg, but she was never able to find anything.

Get daily National news

“She probably died in the war,” she said in her testimony. “But I’m not sure.”

Grebenschikoff’s daughter Jennifer has watched her mother speak to groups about her life over and over, and says the story about Wahrenberg has always made it in.

“Mom would always say, ‘If you ever hear of Anne Marie, please contact me, I’m still looking for her,” she says.

It was a mystery that would have gone unsolved if not for a chain of improbable lucky breaks.

In November, Ita Gordon was invited to attend an online Zoom conference held by a group of museums in South America. Gordon is an indexer with the Shoah Foundation and speaks fluent Spanish. She took part in the conference from California.

The topic was Krystallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. Nov. 9, 1939, angry mobs rioted across Germany targeting Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues.

The speaker for the conference was a last-minute replacement, a 90-year-old woman who had lived through Krystallnacht.

When it was over, Gordon logged onto the Shoah Foundation’s database to see what the organization had about the speaker. While there was nothing specifically about the woman, when Gordon plugged in details about her life, she ended up coming across Betty Grebenschikoff’s search for Anne Marie Wahrenberg.

The speaker’s name was Ana Maria Wahrenberg — Gordon had found two long-lost friends, both of whom thought the other was likely dead.

“I was all alone and I realized I had something,” she says. “That’s when I froze.”

Wahrenberg and her parents escaped Germany several months after the Grebenschikoffs, just days before the start of the Second World War. They were the only members of her family to get out safely — everyone on both sides was killed in death camps.

After the family settled in Chile, they learned Spanish and eventually, Anne Marie changed her name to Ana Maria.

When the Shoah Foundation reached out to the families to tell them what had been found, the first reaction was disbelief. The second was apprehension.

The group could put together a Zoom meeting connecting the women, but did they want to do it?

“Mom never hesitated,” says Jennifer Grebenschikoff. “There was never, ‘Should I do this or shouldn’t I?’”

After 82 years, Betty Grebenschikoff jumped at the chance.

“I talked my whole life about her,” she says. “For goodness sakes!”

The Zoom meeting was held in November and moderated from Germany by the Shoah Foundation’s Karen Jungblut.

Grebenschikoff was at home in Florida, while Wahrenberg was in Chile.

“I just clicked some buttons on my computer and both of them appeared,” Jungblut says. “They started chatting together in German, and I said ‘OK, I’m disappearing.’”

Jungblut and Gordon had spoken before the meeting about the possibility the old friends would run out of things to talk about after five minutes. Instead, they spoke for 50 minutes.

“As soon as she started talking with me, there was a connection right away,” Grebenschikoff says. “It wasn’t like, ‘Who’s this old lady over there?’ Nothing like that.”

The pair talked about their escapes from Germany, their parents, their husbands and their children.

In the first few minutes, Wahrenberg held up a small book with a photograph of Grebenschikoff. Betty had written a note in it eight decades earlier. Now, Wahrenberg read it back to her.

“When one day in later years, you take this small book in hand, think about how nice it was that we knew each other.“

They reminisced about ballet classes, teachers they didn’t like, and how they both ended up married within weeks of meeting their husbands.

Jennifer Grebenschikoff says it didn’t seem like old friends catching up. It was like close friends picking up where they left off.

“It was like they had seen each other the day before,” she says. “It was just very natural. It was so easy.”

For both women, reuniting was a gift they didn’t see coming.

“We went 82 years with zero contact, nothing,” Wahrenberg says. “This is a huge pleasure, a joy, a surprise.”

When Jungblut broke back into the Zoom call, she brought in Gordon, whose detective work had made it all possible.

Being a part of it, Gordon says, felt like magic.

“I was almost numb,” she says. “I thought I would cry, but it was the opposite. I was so happy, and so lucky to witness it.”

That last half hour of the Zoom call was spent on introductions. Both women introduced their sons and daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

“Look what we’ve done, Ana Marie,” Grebenschikoff said, beaming with pride. “Look what we’ve done.”

The two women have a pact to stay healthy in this pandemic. When it’s safe to travel, they plan on meeting in person.

They now have a scheduled call each week, Sundays at noon. But they also email and WhatsApp on other days — basically whenever they might feel like it.

Because 82 years is a lot of time to make up.

See this and other original stories about our world on The New Reality airing Saturday nights on Global TV, and online.

Comments