The question of how to best represent what Black heroism is and — most importantly — how it reflects the era we live in, is one that the comic book world has been answering for decades.

Marvel’s Luke Cage, for example, was a 1970s Blaxploitation riff, DC’s Static felt grounded in a 1990s hip-hop cool, and 2018’s Black Panther personified Black excellence and possibility.

“Black superheroes have often asked us to think critically about heroism, and how things look like politically for a time,” said Chicago native Eve L. Ewing, a professor, activist, poet, and Marvel Comics writer.

READ MORE: ‘It was a gut blow’ — Chadwick Boseman’s death adds to grief, anguish of 2020

“It hasn’t always been about representation, but about the ideas that these characters could bring with them.”

On Jan. 5, DC released Future State: The Next Batman comic series, written by screenwriter John Ridley — also known for 2013’s 12 Years a Slave — and whose explorations flirt with the same question: that in an era of growing police mistrust, it may not be useful for a billionaire Batman to be jailing criminals. Bruce Wayne is instead replaced by Tim Fox, son of Batman’s longtime friend, Lucius Fox. And, in effect, Ridley continues a tradition of Black heroes tackling uncomfortable subjects.

All of which is to say that the context of a Black Batman is important, and only made possible by a Black comic history that’s equal parts honest effort and nobody-knew-better ignorance — the kind needed to pave the way for what’s to come.

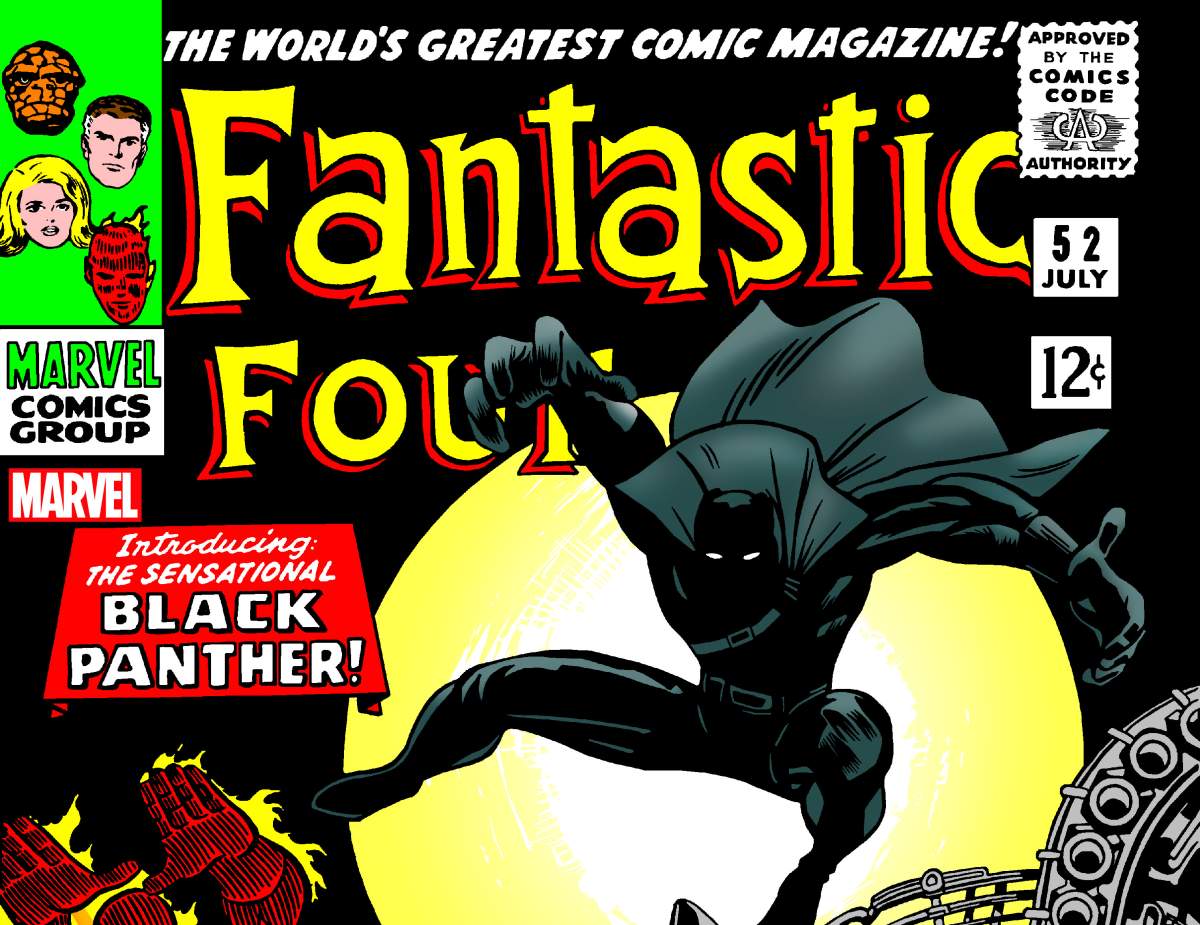

It began with Fantastic Four’s no. 52 issue in July 1966, when an African chief was introduced as “The Sensational Black Panther!”

Both the late Jack Kirby and Stan Lee designed the hero with the well-intentioned idea of a savage-less nation of Africa called Wakanda, a technological paradise. But, while well-intentioned, this early Black Panther was simultaneously progressive and stupidly stereotypical.

“I appreciate the origins of Black Panther from the ‘60s, but I’d never want to see a movie about him from that time period,” said Adilifu Nama, publisher of Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes.

“Like many Black heroes, there were too many kinks in that Black representation armour that needed growth.”

Get breaking National news

It wasn’t until Christopher Priest — the first Black writer to take on the character in the late ‘90s — took over that audiences saw the dignified, non-stereotyped Black Panther who inspires Black joy to this day.

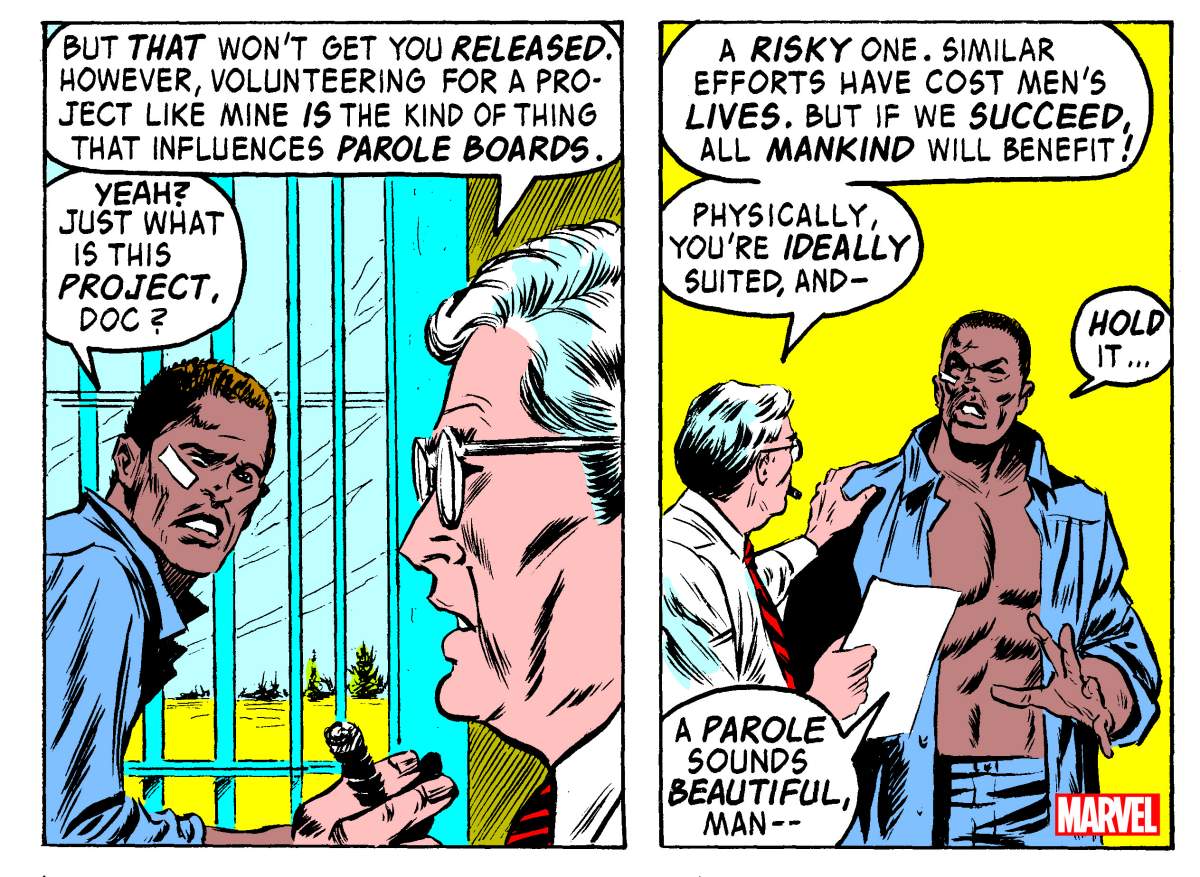

While Marvel’s first attempt was respectable, it was the ‘70s Luke Cage that leaned all the way into a Blaxploitation shtick. Formerly coined Power Man, he was the jive-talkin’ hero-for-hire with a bulletproof skin — gained in prison, of all places.

In truth, the New Yorker, created by writer Archie Goodwin, was every bit the chain-wearing, “sister” and “baby” dialogue-spitting stereotype of his time. But while rough, his panels gave credence to the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, a covert series of 1930s experiments on Black men, and the abusive issues of state power.

Even so, the tagline on the cover of Luke Cage, Hero for Hire No. 1 — “The Cage Goes Wild!” — is still one of the worst kinds of Black parody to this day.

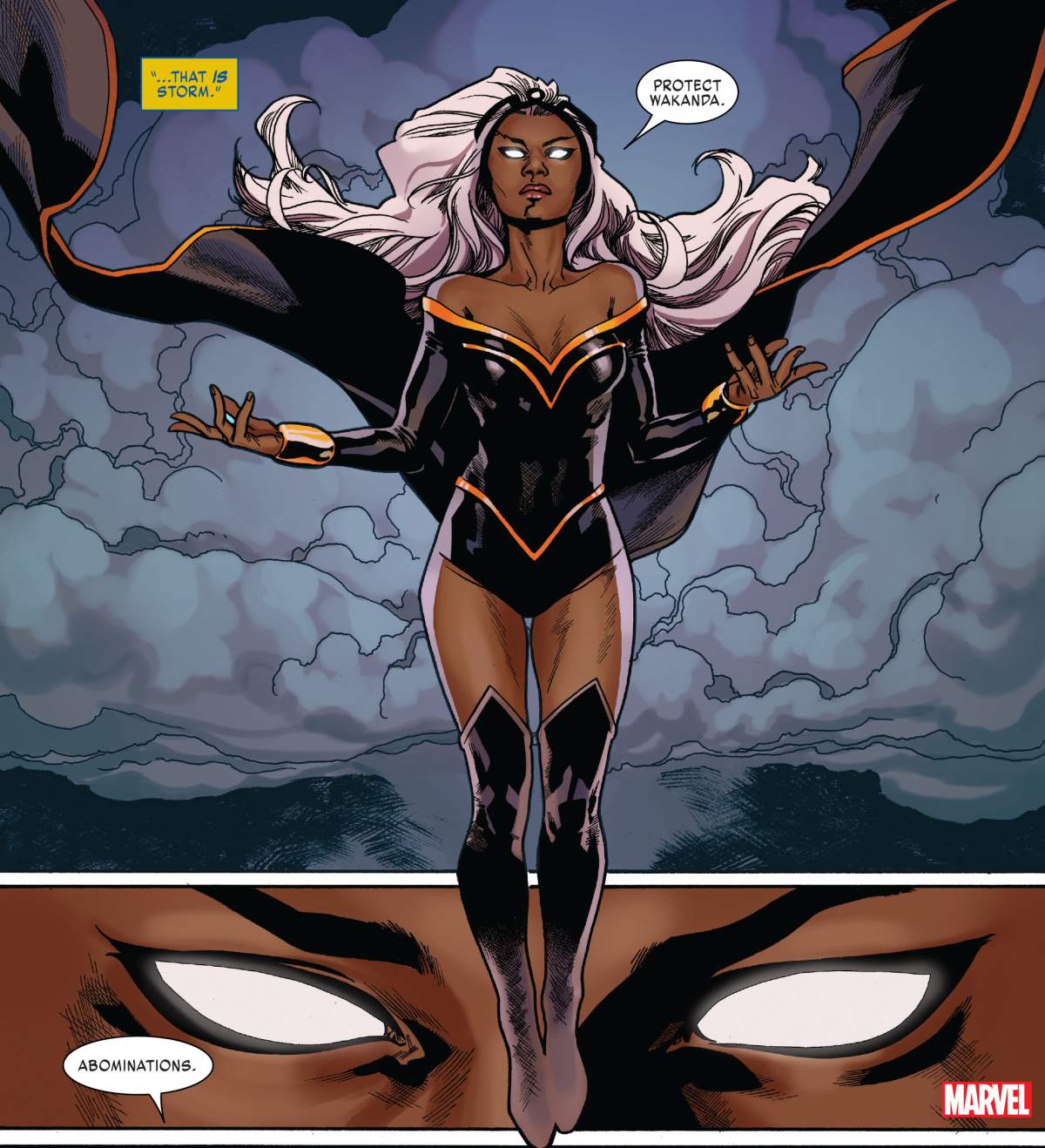

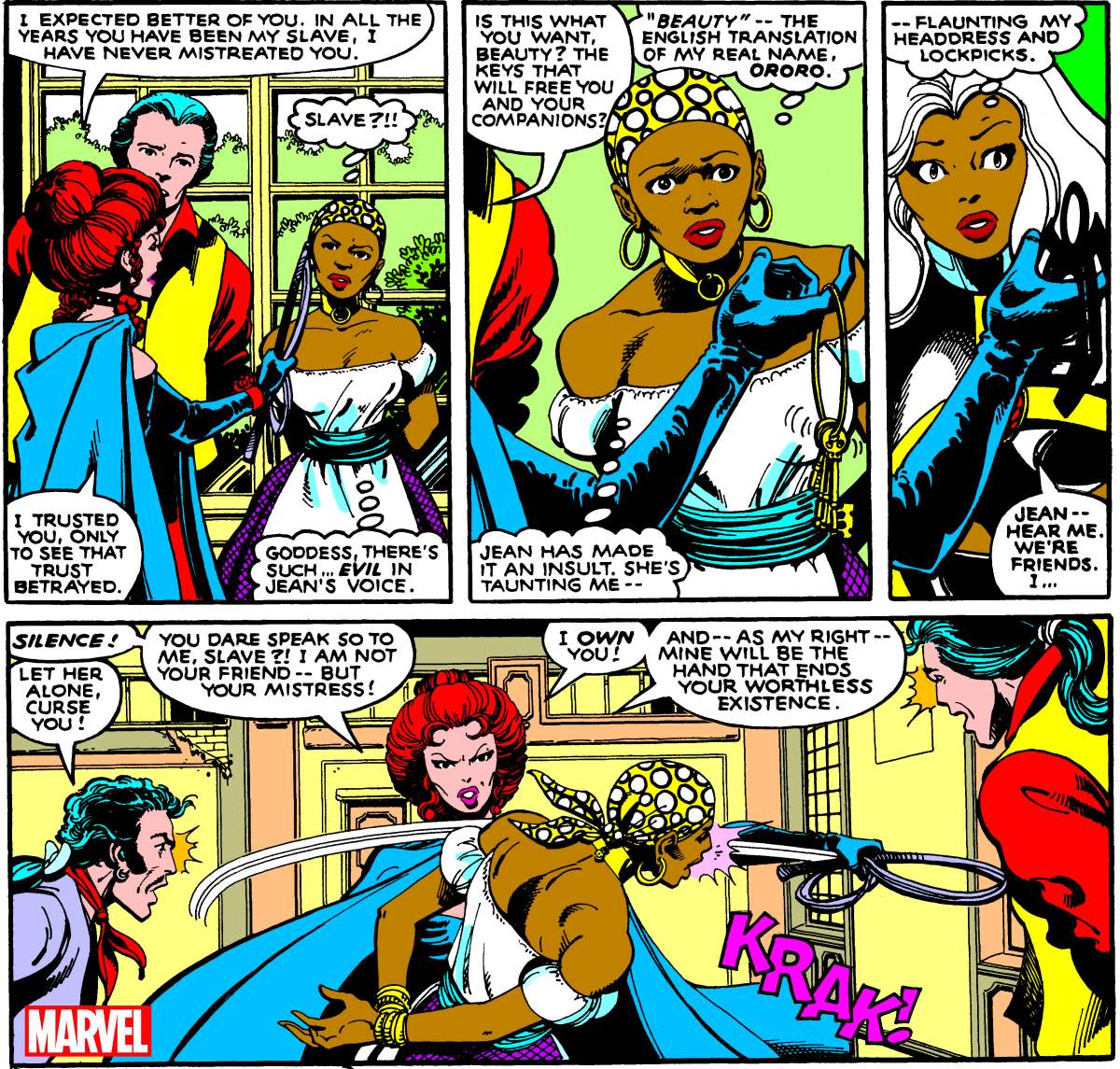

The contrast between Cage and the most popular Black female superhero, Storm, a.k.a. Ororo Munroe, is sadly similar. When writer Len Wein wrote her in through X-Men, she wore the many hats of a slave, street thief, and headmistress — all while being a “strong” Black weather witch.

“It’s still hard for people to portray us in a way that feels true to a Black reader,” said Ewing, who’s had her own particular issues with Black women in comics.

“Some writers, frankly, who are non-Black, still expect Black women to be heroes of perfection, which reinforces the real-life expectation that we’ll just carry everything.”

With over 17,000 comic book appearances since 1975, Storm is still the most idolized Black hero to have never been exclusively written by a Black woman.

The fact that she’s still loved is less about who she is now, and more about what she represents, figuratively and potentially.

A little more than two decades after the ‘70s debuts of panthers, mutants and five years before a vampire-hunting Wesley Snipes-led Blade, Milestone Media would bring a perfect synergy between Black fantasy and reality. In 1993, comic veterans, from Dwayne McDuffie to Christopher Priest, would create a roster of trailblazing content that covered same-sex relationships, gender fluidity, racism, and mental health.

Of the lineup, published by DC comics, Static was one of their more popular creations.

He was a Black kid named Virgil Hawkins who was exposed to a radioactive mutagen that made him electromagnetic. Through his city boy spunk, Static covered topics from outright racism to homelessness — proving that Black readers were hungry for political awareness.

Fast-forward to today, and we have the coupling of a thinker in John Ridley with Batman, which is, well, hopeful. Black heroes are coming into their own in that sense.

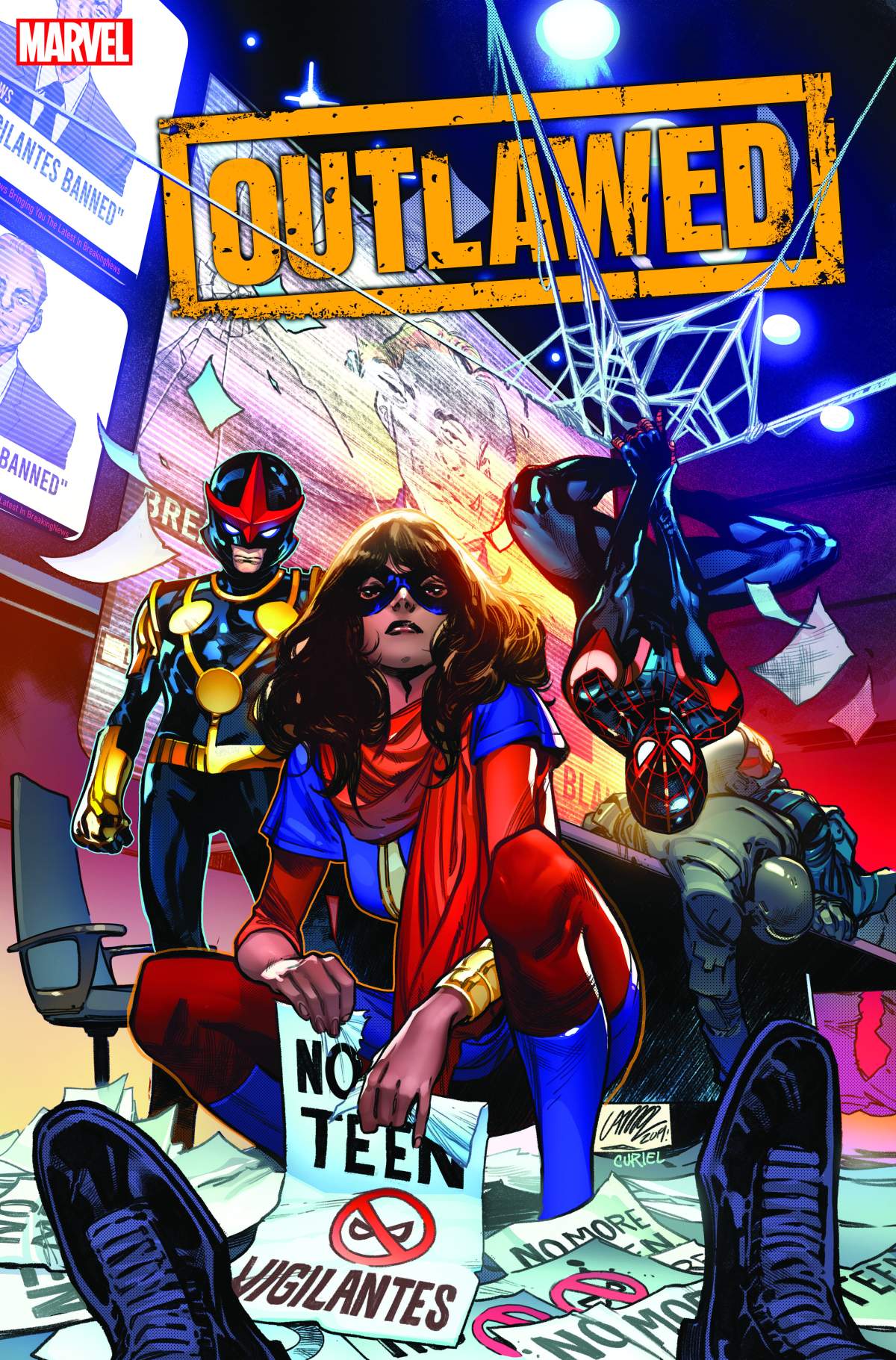

Marvel’s new Iron Man, for example, is now a Black woman known as Riri Williams. The mantle of Spider-Man is joined by an Afro-Latino New Yorker in Miles Morales. And we have Ran Coogler’s Black Panther, the billion-dollar blockbuster led by a figurative and literal hero in the late Chadwick Boseman.

“A huge emotional appeal in the future of Black superhero stories is wish-fulfillment,” said John Robert Cole, co-writer of the film Black Panther.

READ MORE: Michael B. Jordan breaks silence on Chadwick Boseman death: ‘I wish we had more time’

“Black people seeing their own greatest, in a way that Black heroism can offer. The opportunity for us to explore possibilities in a Black image through our lens remains for a lot of us, myself included, a joy to be a part of.”

Noel Ransome is a Toronto-based freelance pop-culture and entertainment journalist. He was previously a full-time culture critic at VICE and associate editor at Urbanology Magazine. Follow him at noelransome.com and on Twitter @noelransome.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.